Our Buyer’s Guide: Stablecoin Payment Infrastructure is now available to license (learn more about purchasing a subscription or read the executive summary), so we’re continuing to explore the technical side of stablecoin payments. This week our focus is on stablecoin wallets, how they work and why it matters to stablecoin infrastructure design.

Anyone who holds or has held any form of cryptocurrency – be it a stablecoin or something more volatile – is likely to have at least a basic understanding of what a wallet is in the digital asset space. For most people, an on-chain digital wallet is a value store, not unlike a fiat-based digital wallet or even a physical wallet used to store cash.

However, while true enough from a user experience perspective, that is not quite accurate from a technical point of view. While other forms of wallets are essentially just specialised containers, on-chain digital wallets are not actually virtual buckets for cryptocurrencies but are instead a cryptographic identity in the form of a public address with a set of rules applied to it, which is secured by at least one virtual private ‘key’.

As we previously explored, stablecoins and other cryptocurrencies do not differentiate between different individual tokens, so there is no specific identifier for one USDC token versus another, which means wallets cannot ‘hold’ a specific USDC coin. Instead, there are records of the amounts minted onto different blockchains and within this, which wallets they are held in.

Digital assets must be assigned to a particular address/wallet – they cannot just exist on a blockchain without an assigned location – and each wallet can be configured to support assets on that blockchain, as well as multiple blockchains with their own token standards. Beyond this, however, they can also be configured to follow different rules.

These rules govern how and when a wallet can initiate or receive transactions, and ensure that the balance assigned to the wallet is agreed by the wider blockchain it is connected to. Rules can include limits on the amount of a given token that can be stored or sent in a single transaction, the frequency of monitoring, which accounts funds can be moved to from the wallet and how much their activities are monitored.

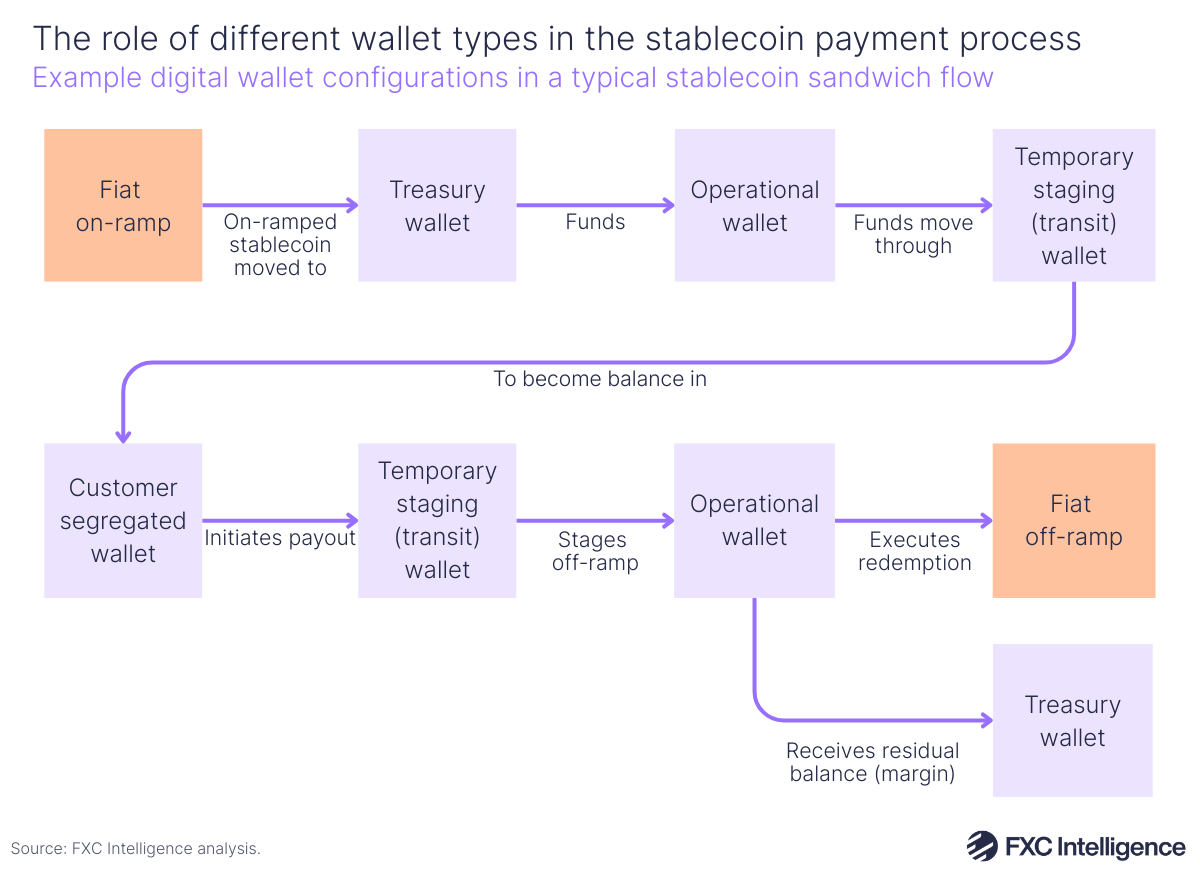

This is important because across stablecoin payments infrastructure, wallets are deployed in a wide variety of different ways, and the right set of rules for one use case may be completely inappropriate for another. Examples include:

- Operational account wallets: Used by payments providers for key steps in on-chain payment processing, including receiving stablecoins after funds have on-ramped, executing outbound transactions and funding downstream settlement flows. These wallets generally have heightened security, including requiring multiple approvals or a rigid framework of permitted actions and approved destinations.

- Treasury balance wallets: Used to hold a provider’s stablecoin reserves for liquidity management, pre-funding and similar. Typically see low numbers of transactions but high balances and often feature time-locking or delayed execution, as well as high levels of logging to support compliance and transparency.

- Temporary staging wallets (transit accounts): Used as a step in wider settlement processes, these wallets typically only have balances for seconds at a time and are usually set up with very narrow rules around their use, including high levels of automation.

- Customer-segregated balances: Used to hold the balances of individual customers, and not always required in all markets or for all product types. These typically require high levels of mapping and clear reporting, as well as consistent rules that can be applied to large numbers of wallets at scale.

Next week we’ll continue to explore wallets further, with a look at their security, as we continue to mark the release of FXC Buyer’s Guide: Stablecoin Payments Infrastructure. Find out more about how it can help your business navigate stablecoin payments infrastructure and learn more about a paid subscription.