To mark the launch of our Buyer’s Guide: Stablecoin Payment Infrastructure, which is be available to license via subscription (learn more about purchasing a subscription or read the executive summary), this series takes a deeper dive into the technical details of stablecoin payments infrastructure. While last week our focus was on stablecoin liquidity, this week it’s all about multi-chain issuance and what it means for utilising stablecoins in payments.

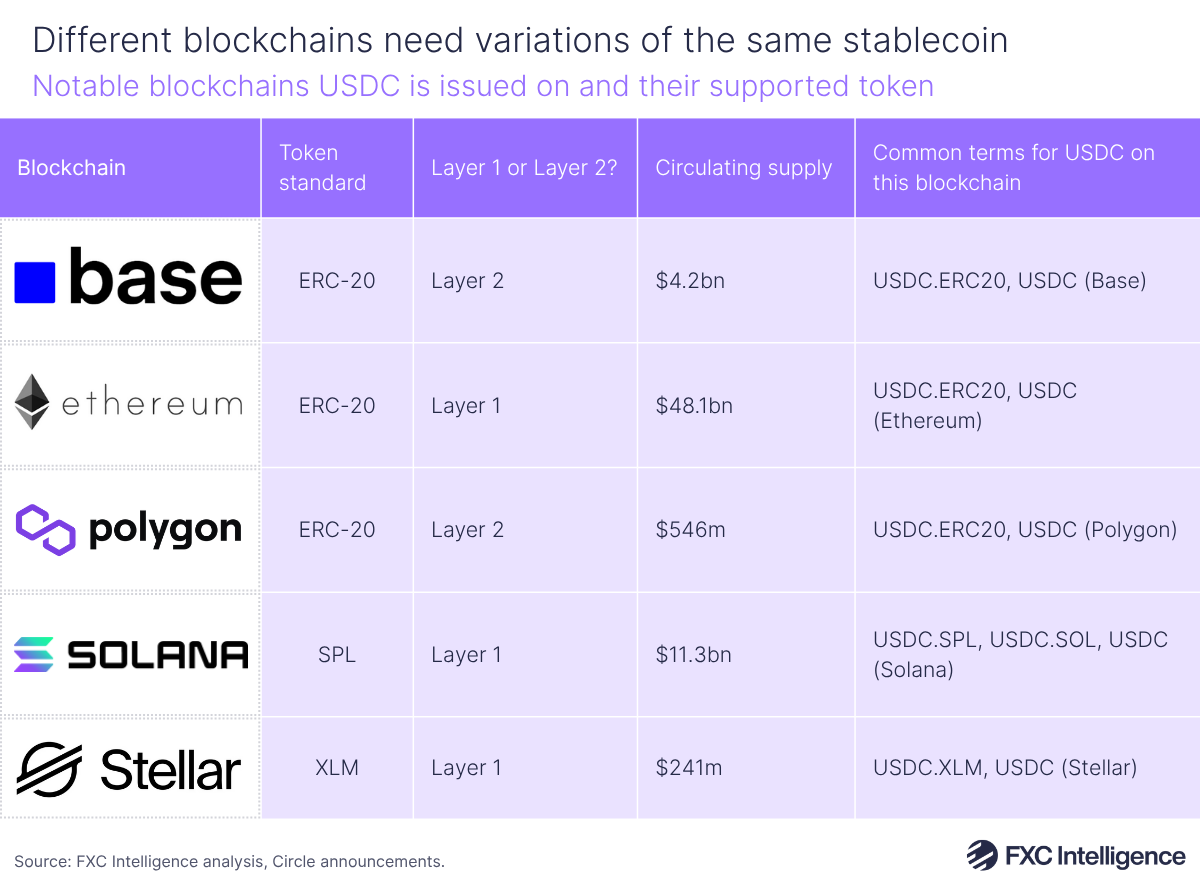

If you’ve ever looked at documentation from stablecoin infrastructure providers, you may have noticed that the supported assets lists from many providers will include multiple instances of the same stablecoins. For example, you may see USDC.ERC20 – sometimes written USDC (ETH) or similar – listed alongside USDC.XLM and many others, while USDT.ERC20 might be accompanied by USDT.TRC20 and many others.

This is because not all forms of the major stablecoins, such as USDC and USDT, are the same – there are multiple types, depending on the blockchain they run on. The USDC that runs on the blockchain Ethereum (sometimes noted as USDC.ERC20) is a different token from an operational and technical perspective than the USDC token that runs on Stellar (USDC.XLM).

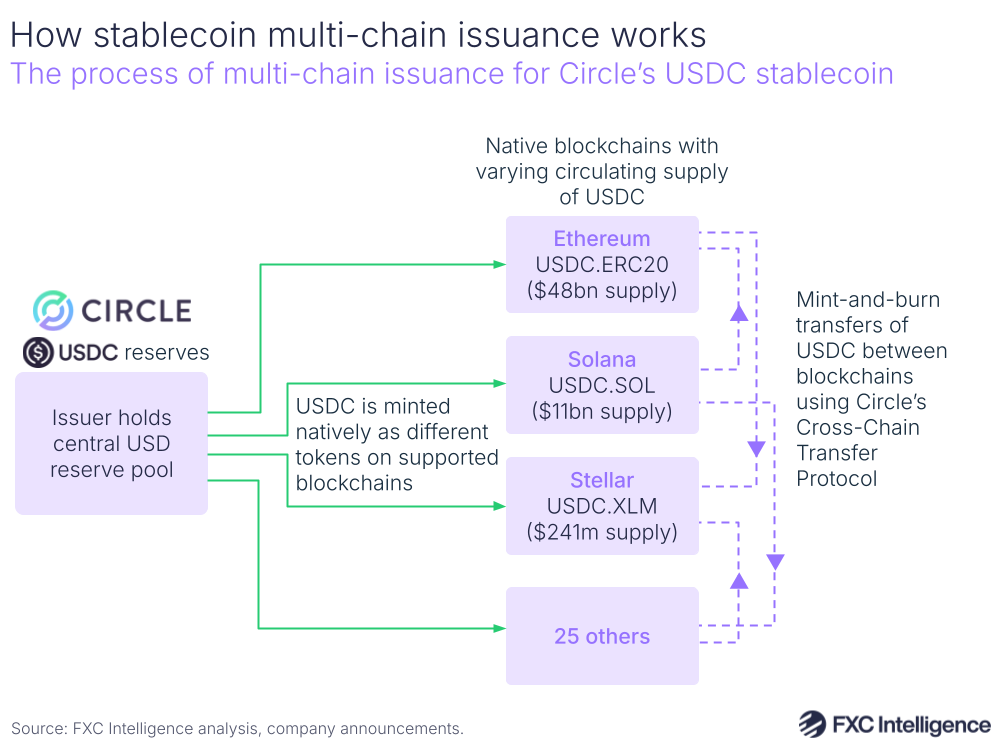

This is because many stablecoins support multi-chain issuance – that is, the ability to be minted natively on several blockchains. However, different blockchains differ technically from each other in many ways. They each have their own programming environment, typically using different languages for smart contracts that often employ different financial logic. They can therefore use different mechanisms to reach consensus to create new blocks, have different settlement times and even different compliance solutions.

As a result, the tokens that operate on them have to also vary, in a similar way to how a company’s app running on iPhone is technically different to the one running on Android. Each of these tokens have to be separately integrated into stablecoin infrastructure, including into wallets and APIs, and so it is typical to have infrastructure that only supports certain token types.

This means that if a payment has been on-ramped into one version of USDC, the solution to off-ramp it will need to support that token specifically if the transaction is to proceed without an additional conversion. Different token types also see larger or smaller quantities of the stablecoin in question in circulation – referred to as a liquidity pool – which can impact their utility for larger transfers or their ability to be easily on and off-ramped. The more blockchains a stablecoin is supported by, the greater the risk of cross-chain asset fragmentation. However, different properties of different blockchains, such as their transactions per second and gas fees, make them better suited for different applications, creating a need for them to be available on multiple chains.

Meanwhile, Layer 2 blockchains, which are blockchain infrastructure that sit on top of foundational Layer 1 blockchains, use the Layer 1 blockchain’s token standard – meaning the same form of USDC – but with some architectural and operational differences in how they are deployed in reality.

Multi-chain issuance’s various challenges are offset by the fact that a token can be moved between different blockchains using one of a few techniques. If a token is being moved between two blockchains where it is issued natively, such as moving USDC from Solana to Ethereum, it can be moved in a process known as a native transfer using a burn-and-mint mechanism, where the token is burned on the first chain and re-minted on the second chain by the same issuer. For USDC, Circle has its own solution for this, known as the Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol (CCTP).

However, if a token is being moved to a blockchain that it is not natively supported on, it can be moved in a process known as bridging, using a lock-and-mint mechanism where the token is locked in a smart contract on the first chain and then a wrapped version – a synthetic version of the stablecoin – is minted on the second chain.

While native transfers are typically managed with robust protocols, such as Circle’s CCTP, bridging comes with greater risks, particularly from a security perspective, and within cross-border payments, providers typically stick with commonplace forms of USDC on native blockchains.

Next week we’ll be digging into more topics related to stablecoin infrastructure. If you’re considering the potential of the technology, FXC Buyer’s Guide: Stablecoin Payment Infrastructure is designed to identify best-in-class providers that fit your needs and help you make sense of the market. Learn more about how it can help you and express interest in subscribing.