Stablecoins have seen growing attention in cross-border payments and beyond. But where are they having a genuine impact? In this landmark in-depth report, we explore the technology’s opportunities and challenges – with insights from some of the most important players in the industry.

For the cross-border payments industry, it’s clear that 2025 is the year of stablecoins. New announcements about projects using the technology are being made on an almost daily basis, while landmark regulation is bringing stablecoins deeper into the traditional ends of the market.

“We are entering a period of escape velocity in terms of everyone recognising this is a new and upgraded payments technology,” explains Chris Harmse, Co-Founder and Chief Business Officer of BVNK, a provider of enterprise-grade stablecoin infrastructure.

“There’s real businesses and real use cases happening. It’s not some sort of crypto fad and the adoption is real.”

But as with any technology attracting such enthusiasm, there are also claims made about stablecoins and their applications in payments that struggle to hold up to scrutiny.

“Sometimes when you scroll through LinkedIn or attend conferences, it feels like stablecoins are being hyped as the solution to everything – like they’re about to solve world hunger or cure cancer. It’s a bit much,” says Eric Barbier, CEO and Founder, Triple-A, a B2B digital currencies payments solution provider.

The market is fast-moving, with many players seeing rapid development of both their businesses and the mix of companies that are engaging with them. It’s clear that there are benefits to be had, but with at times significant technical complexity surrounding stablecoins, understanding where they lie can be a challenge.

This report is written in response to that challenge. Drawing from FXC Intelligence’s cross-border payments data and expertise, extensive research and the insights of 14 leaders from key companies across the industry, it provides a detailed primer on the state of the industry and where the opportunities lie – including the current total addressable market for cross-border payments using stablecoins.

In order to ensure this can be shared widely, we’re making it available both as a PDF and in the digital form on this page. You can access both after the login below (or by scrolling down if you are already logged in), but if you are from a bank whose internal policies impact your ability to sign up, please email us to request a copy. Given the at times complex nature of the topic, we’ve also included a stablecoins 101 glossary of terms, which you can access by scrolling to the end of the report, or via the clickable section panel that appears immediately below this text and between each section. And if you want to know more about how FXC Intelligence is supporting companies entering or working in the stablecoin cross-border payments space, you can find out more on our stablecoin data product page.

The changing stablecoin landscape

As a technology, stablecoins are relatively young, but have seen a recent surge in transformation, both in terms of how the industry perceives them and the types of companies that are exploring their use.

“It’s changed more rapidly over the last two years to 18 months. There was this wave of stablecoin adopters, all the typical higher risk sectors, but sectors that had arms and legs in emerging markets,” says Chris Mason, Co-Founder and CEO of Orbital, a stablecoin-led B2B payments platform.

“Now we’re starting to see more and more PSPs [payment service providers] and banks – they’re recognising the next wave.”

However, this recent jump in interest is more than 15 years in the making – and the sector has endured considerable growing pains in that time.

“There is a recognition now of the utility of the technology, which has been in development for a really long time,” says Iana Dimitrova, Chief Executive of OpenPayd, a fiat-led financial services infrastructure provider.

A brief history of stablecoins

Stablecoins have their roots in the 2008 invention of cryptocurrency: a tokenised, decentralised and immutable form of digital currency running on digital ledger-based rails known as blockchains. They first emerged with bitcoin, which was introduced to the world in October of that year when an unknown researcher working under the alias Satoshi Nakamoto published a paper entitled ‘Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System’.

From the outset, bitcoin was framed as a means of making online payments while bypassing the need for financial intermediaries. However, while there was some limited payments experimentation from its early adopters, it largely gained popularity among internet natives and technologists using the cryptocurrency for speculation.

As interest grew over the next few years, there were some attempts to capitalise on the underlying technology for cross-border payments. But many struggled to take crypto seriously as a technology for payments due to its significant price volatility, as well as its lack of regulatory oversight and some associations with black market activity. That changed, however, with the introduction of the stablecoin: a key moment in the development of blockchain-based technologies that saw it move from the equivalent of the early internet to the beginnings of the modern era.

“Stablecoins were the equivalent of Napster being built,” explains Teymour Farman-Farmaian, CEO and Co-Founder, Higlobe, a provider of USD receiving accounts to emerging markets businesses.

The first digital currency to be launched as a stablecoin was known as BitUSD, which introduced the idea of a cryptocurrency pegged 1:1 with a fiat currency, in this case the US dollar, in 2014. However, as this was backed by cryptocurrency, it does not fully fit the definition of what we know as a stablecoin today.

Others quickly followed, but it was Tether who introduced the idea of reserves in fiat currency when it launched USDT later that year. Over the next few years, it grew in popularity and interest, but also faced questions around transparency and regulation and ultimately took significant steps to address these.

In this early era of stablecoins, developers were building an understanding of what a stablecoin was and how it could be used, with several other coins launched as others developed their own iterations. In 2018, however, more regulated stablecoins began to emerge, with Paxos launching what is now known as the Pax Dollar (USDP) and Circle launching USD Coin (USDC) via a consortium with Coinbase.

These regulated and, crucially, US-based stablecoins began to see growing popularity, with interest coming not only from the crypto-led space, but some in the mainstream financial industry. Meanwhile, financial infrastructure players built on stablecoins also began to emerge, including Fireblocks in 2018 and BVNK in 2021.

However, stablecoins faced something of a crisis in confidence in 2022 and early 2023, when several incidents rocked the space. The first was the sudden and dramatic collapse of TerraUSD (UST), a highly unorthodox stablecoin that was backed not by cash reserves but by an algorithm-based mechanism. This resulted in its value dropping significantly from its $1 peg, with the resulting panicked trading seeing a number of other stablecoins’ values also briefly wobble in major markets.

While UST was not a conventional stablecoin, the reputational damage for the wider industry was notable, despite attempts by Circle, Paxos and others to distance themselves from the algorithmic stablecoins. However, while many were reassured by statements put out by such players that their reserves protected them from such issues, the early 2023 collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) raised new questions.

At the time of the collapse, Circle had around $3.3bn of its reserves with SVB, and there was initially uncertainty about whether the deposits would be guaranteed. This prompted what became known as a ‘shadow run’ on USDC, as holders worried they would not be able to redeem the stablecoin for its 1:1 value, which led its trading value to drop to its lowest level in the stablecoin’s history.

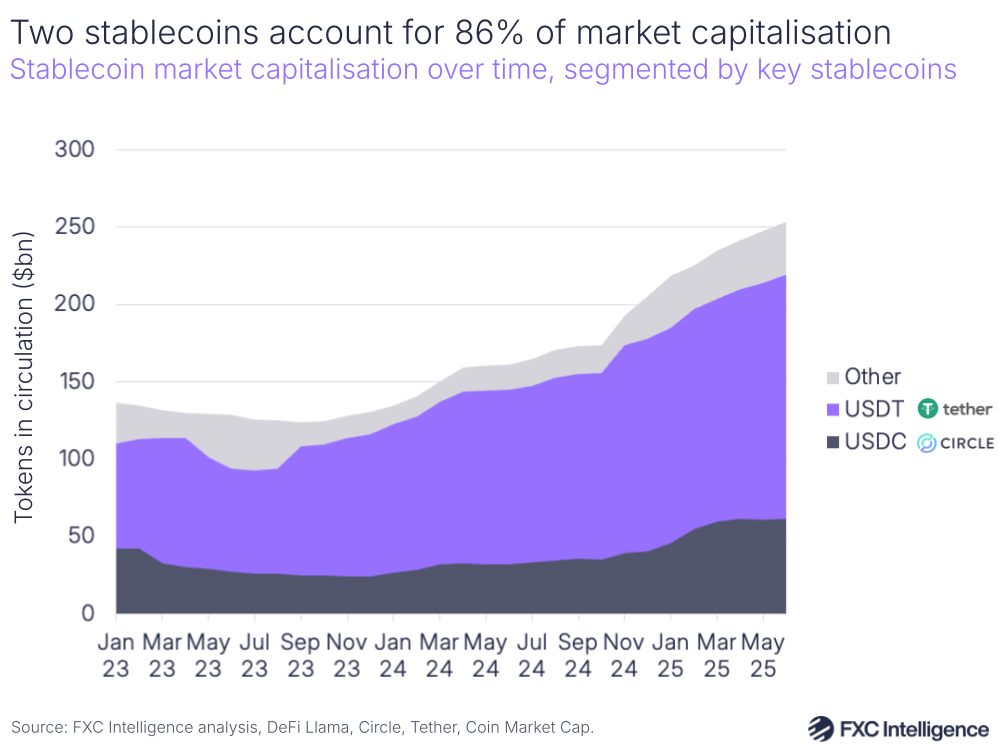

While the US government ultimately did guarantee SVB’s reserves, and Circle at no point was at genuine risk of being unable to redeem holdings of USDC, the reputational damage was this time more severe, particularly among institutions requiring robustly backed stablecoins with US-based reserves. While overseas-based USDT continued to see adoption climb, US-based USDC saw the number of its tokens in circulation decline steadily over 2023.

Slowly, however, a streamlined, more robust version of the industry began to rise from the ashes of this period of crisis. Infrastructure companies, driven by genuine demand in key corridors and verticals, were seeing their volumes and adoption rates climb, and evolving their products in response, while others were launching products focused on the genuine utility they saw in the technology. Later in 2023, PayPal gave a critical vote of confidence to the industry when it launched PayPal USD (PYUSD), while others worked to educate those less sure of stablecoins to build both regulatory frameworks and greater adoption.

“The education piece is really tough, but people are really starting to understand it,” says Orbital’s Mason.

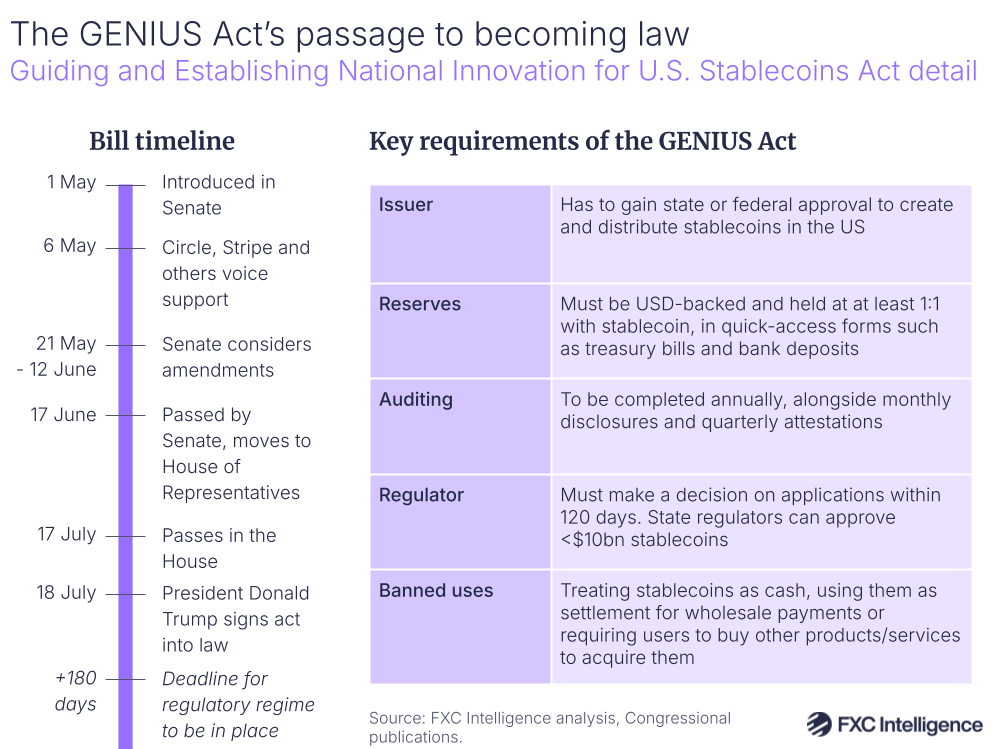

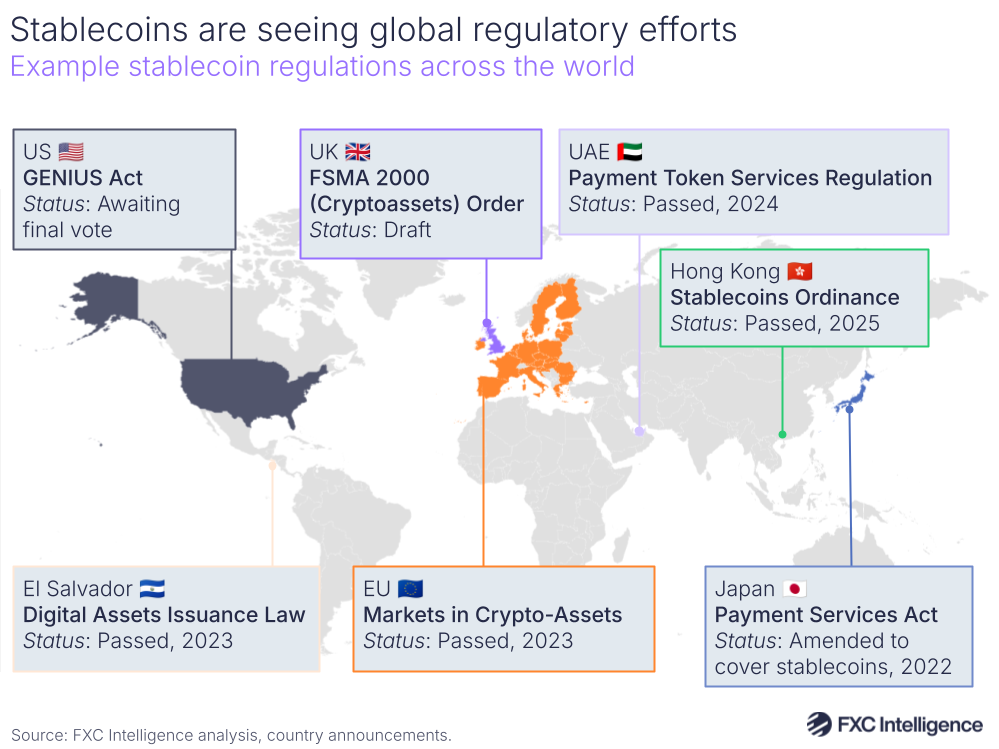

From early 2024, USDC’s number of tokens in circulation began to again climb, and the number of new launches focused on payments continued to grow. The more recent return of Donald Trump to the US presidency has also increased institutional support for the technology, with incoming regulation in the form of the GENIUS Act.

“Certainly since the US administration has changed, major financial institutions are approaching companies like ours for help on where and with whom they can start to work with stablecoins in a regulated fashion,” says Guillaume Kendall, Director, Business Development – EMEA Crypto Natives, Paxos, a stablecoin issuer and infrastructure provider.

Now, with adoption climbing more rapidly and the cross-border payments industry taking significant interest, there is further growth on the horizon, but the essential principle of stablecoins remains much the same as the initial premise set out in Nakamoto’s bitcoin paper.

“We’re solving for cash on the internet,” explains Nikhil Chandhok, Chief Product & Technology Officer at Circle, a stablecoin issuer and infrastructure provider.

Growing interest from cross-border payments

Alongside the rise of stablecoins as a technology has been the emergence of use cases for cross-border payments. And while, as Paxos’ Kendall explains, usage is still largely dominated by “crypto-native activity”, there is growing interest in their use within the sector, which builds on interest initially generated by end users.

“The journey with stablecoins started on the trading and investment side, and then slowly, through 2022, 2023, it managed to get a pretty strong grassroots hold in the cross-border space,” says Michael Shaulov, Co-Founder and CEO, Fireblocks, a digital asset infrastructure provider.

“Initially, it was mostly companies that were basically crypto-native payment players that were helping their end businesses to move money more efficiently between those corridors.”

This is an experience that is reflected by many in the space, including business-to-business (B2B) payments-focused Conduit. However, in the last year or two things have begun to change.

“I see a major shift where a lot of companies, especially larger multinational enterprises, are coming to us looking to understand how they can use stablecoins, especially in difficult quarters like in Africa, Latin America, Asia,” says Kirill Gertman, Founder and CEO, Conduit, a provider of stablecoin-based international business payments.

This has also seen previously fiat-focused providers of cross-border payments infrastructure also enter the market, such as OpenPayd, which added stablecoin capabilities earlier this year.

“That evolution for us was completely organic, simply because we had a number of our already existing clients that were using us for cross-border fiat payments, coming to us and saying, ‘We are already accepting payments in stablecoins through other providers. Could we bring those assets under your platform?’,” says OpenPayd’s Dimitrova.

“Over the past 18 months we’ve kept receiving those requests on a recurring basis. We realised we were leaving a growing portion of the needs of those customers underserved without being able to provide that interoperability.”

Such requests are led by those with global trading needs, but there has also been growing adoption in other aspects of cross-border payments, including MoneyGram, which began offering the ability to send remittances in USDC in 2022, but has since expanded its capabilities in the space to include white-label digital wallet on-ramping and off-ramping solution MoneyGram Ramps, as well as supporting its own cross-border treasury needs.

“Stablecoins are going to play a very big role in MoneyGram’s future. It helps every element of our business, from the B2B back office to the B2C of how we deliver the service to our consumers,” says Anthony Soohoo, Chairman and CEO of MoneyGram, a fintech with a global digital and cash network.

Other long-established cross-border payments players exploring the technology include Western Union, which has begun to use stablecoins to improve settlement in some Latin American and African markets and is currently exploring adding on and off-ramp support for customers as well as offering wallet-based solutions.

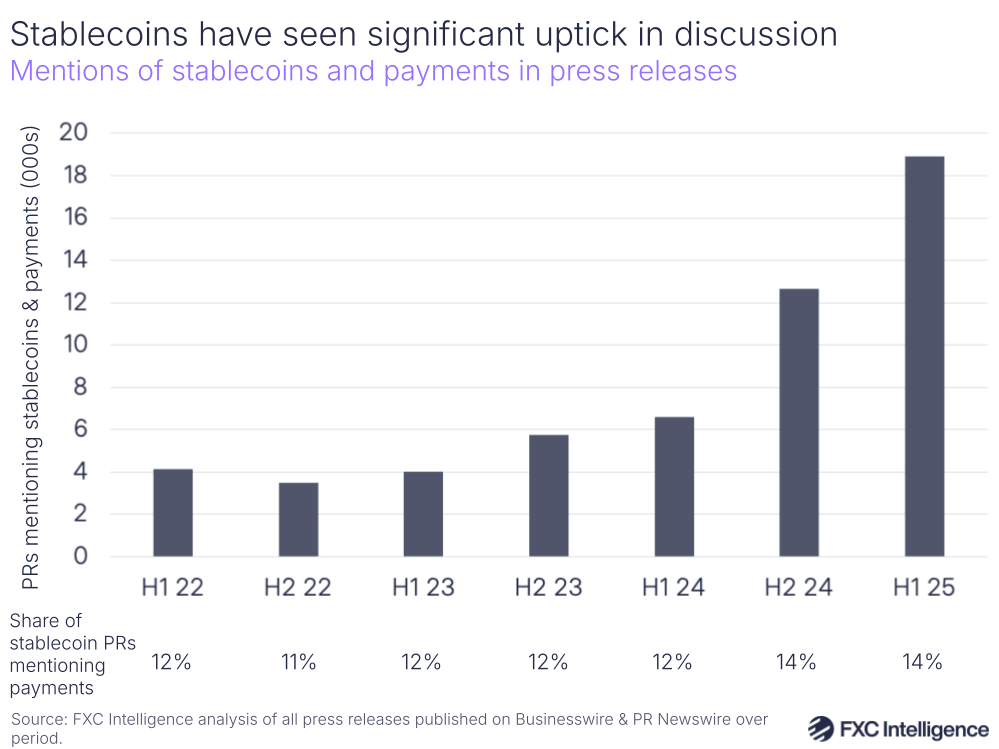

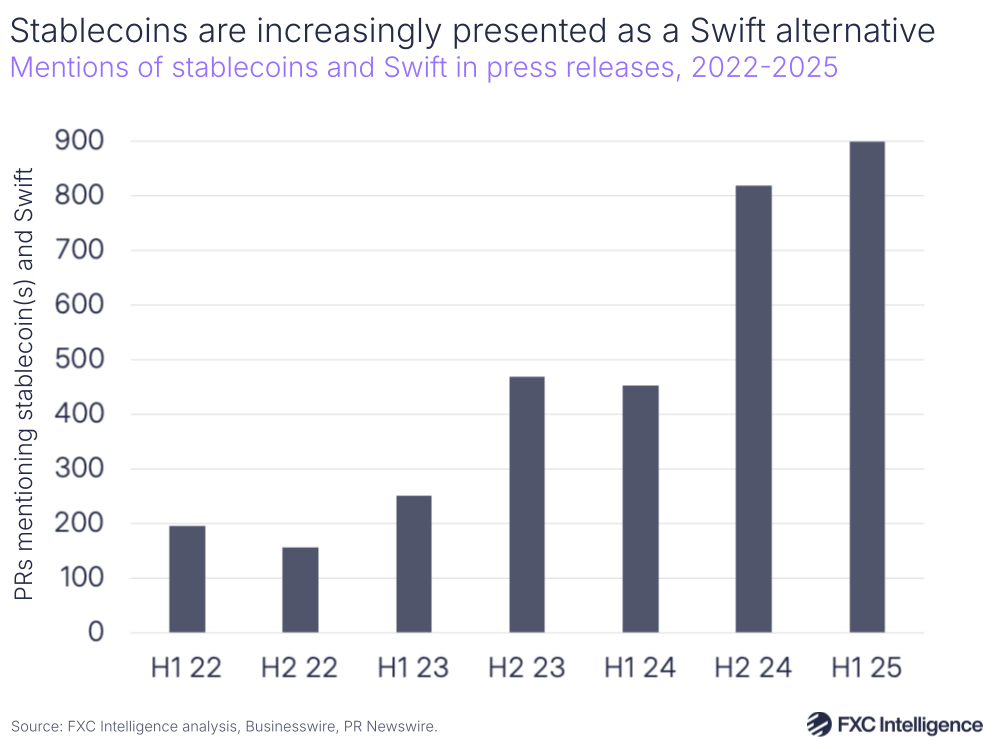

Today, despite stablecoins representing such a small fraction of the market, there is a clear upswing in focus. In H1 2025, the number of press releases discussing stablecoins and payments grew by 186% compared to the same period the previous year – a stronger growth than the rate of press releases discussing stablecoins overall – while those discussing cross-border payments and stablecoins saw an even sharper jump, increasing by more than 1,000%.

And that is the companies publicly launching stablecoin solutions. According to BVNK’s Harmse, the overwhelming majority of those in the payments industry are recognising opportunities in the technology, even if they are not yet publicly discussing it.

“I think 95% of them see that,” says BVNK’s Harmse. “Of the conversations we’re having and the pipeline that we have, it’s definitely traditional payment companies that are leaning in, even ones that you would’ve thought wouldn’t be leaning in.”

Increased investment in stablecoin payments

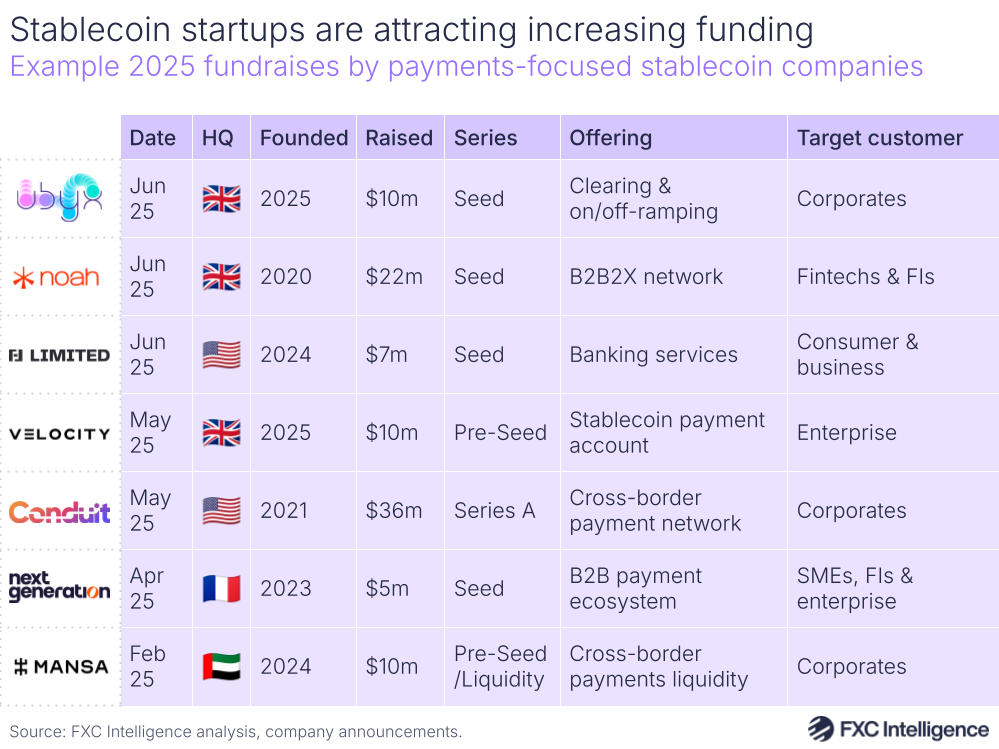

Alongside interest from established players, there has also been growing investment interest. Despite a more broadly challenging venture capital environment, stablecoins have been attracting considerable support, with large numbers of players announcing fundraises in the last year or so.

“Primarily investors are attracted to the possibility of returns,” says Conduit’s Gertman, whose company raised $36m in a Series A round in May.

“When they saw our traction in terms of revenue and in terms of volume – how quickly the adoption curve is growing – they were really interested because they believe that there is a possibility for us to win a much larger market than we have today.”

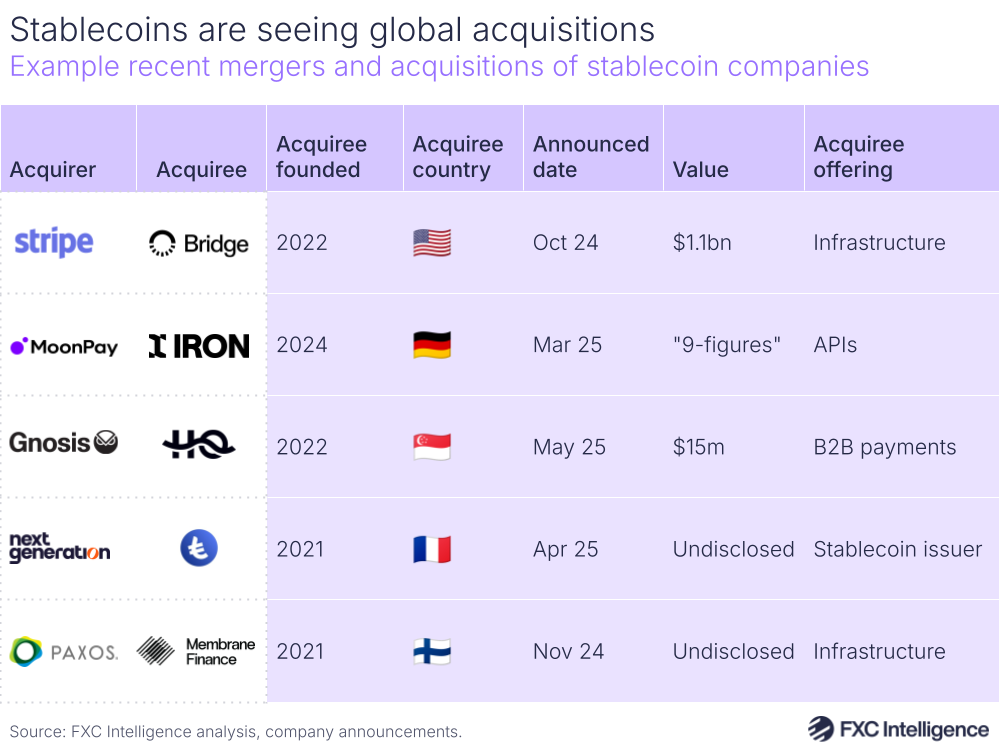

Meanwhile, there have also been a number of acquisitions, as established players look to quickly grow their capabilities in the sector. And while there have been a number of key moves, Stripe’s acquisition of stablecoin infrastructure player Bridge, announced in 2024 and completed in early 2025, is widely seen as a catalyst for the industry taking the technology seriously.

“It prompted a serious look from everyone,” says BVNK’s Harmse. “We were already talking to many of the world’s largest payment companies, but it just accelerated those conversations.”

For some, however, the move goes further, with Jack Zhang, Co-Founder and CEO of Airwallex, a global payments and financial platform for businesses, describing Stripe as “a master of creating narratives” with the move.

“They leveraged this acquisition to create a massive brand and put stablecoins on the map and it almost helped create the current stablecoin phenomenon.”

How is FXC Intelligence helping companies to develop a stablecoin strategy?

The cross-border case for stablecoins

The inherent argument for stablecoins as a means of moving money across borders is that, at least in theory, it is better on several fronts than currently dominant approaches.

“When you stack up stablecoins as a payment rail versus traditional payments payment rails, it wins hands down because of speed, reliability and transparency,” says BVNK’s Harmse. “There’s some work we’ve probably got to do on cost, which more liquidity drives.”

In reality, while there are many examples of where it is already proving effective, there are complexities to delivering stablecoin payments that can make it challenging, and the fact remains that the relatively small scale of the technology’s use for payments means there are still aspects being proven.

However, at the heart of understanding stablecoins and their potential for cross-border payments is this: from the customer’s perspective, this is not about stablecoins.

“Users don’t give a damn about stablecoins. Be 100% truthful; underline that,” says Higlobe’s Farman-Farmaian.

“Users care about the same three things they’ve cared about for the last 3,000 years of money transfers. Number one, security; number two, speed; and number three, best price. They don’t care about anything else.”

Instead, where stablecoins are meaningfully proving out is where they are demonstrating a genuine, reliable improvement on the payments status quo, and that, at least for now, is overwhelmingly in the emerging market space.

The emerging market opportunity

From payment infrastructure players who have been in stablecoins from the outset, to those only recently moving into the sector, the argument for stablecoins is extremely consistent: markets where payments infrastructure is poor not only represent a critical current market for stablecoins, but have in many ways driven the development of stablecoin-based cross-border payments as an industry.

“Global marketplaces that have really felt the pain point of either collecting or dispersing, or holding in markets where the infrastructure is not well-developed,” explains OpenPayd’s Dimitrova.

“They have been exploring alternatives on how to solve their problems quietly in the background. It’s just that the establishment of traditional financial institutions are finally recognising this.”

This not only includes those looking to more affordably and efficiently send money across borders to and from such markets, but also those struggling to access payment instruments they can use internationally or with challenging local currency environments.

“On the agent side, there are businesses that themselves can be challenged to get banking products, where we could provide them a B2B type wallet and then settle with them with stablecoin,” says Luke Tuttle, Chief Product and Technology Officer at MoneyGram.

As we discuss in detail later in this report, the needs for emerging markets are by no means homogenous and the rise of one use case has often begotten further use cases that have broadened demand. However, it is clear that the significant and growing volume of payments along what are often described as exotic corridors is creating a significant market that many in the stablecoin industry have moved to fulfil, with increasingly sophisticated clients among their customerbase.

“We’re working right now with an airline that needs to be able to collect payments in a number of countries in Africa and send those payments to their headquarters in Europe,” says Conduit’s Gertman. “There’s this wave of interest, and to the extent that they can figure out what the use case is quickly, they’re jumping in.”

This increase in sophistication is not only occurring on the client side, but also among partners in emerging markets, who are often crucial to facilitating the on-ramping and off-ramping process, as Orbital’s Mason, whose company provides stablecoin-based B2B and business-to-consumer (B2C) payments, explains.

“We have a lot of local partners around the world, so we could probably support 80-90 currencies today,” he says. “Because of this stablecoin frenzy, the marketplace is now starting to change in that there’s a lot more sophisticated partners available in these emerging markets.”

How stablecoin payments work: The stablecoin sandwich and beyond

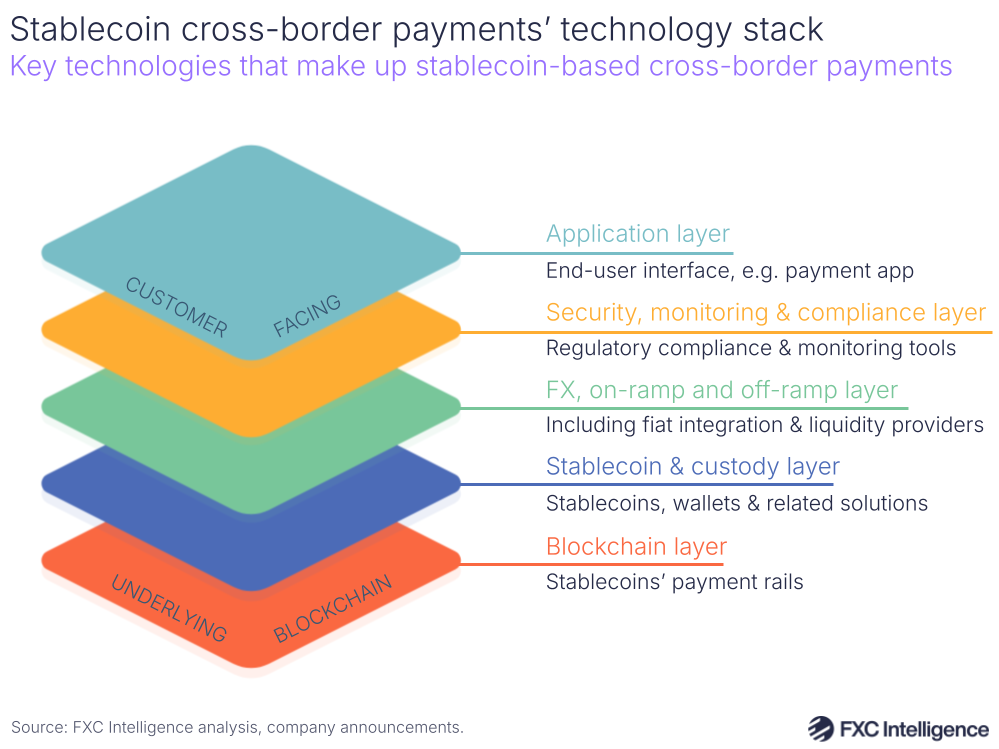

When used to facilitate a payment, stablecoins themselves are one part of a broader technology stack. As part of the custody layer, the virtual coins themselves are moved between holding instruments known as wallets on blockchain networks – rails built on digital ledger technology that make up the blockchain layer.

Above this, however, sit the solutions that facilitate movement in and out of the blockchain space, in the form of foreign exchange and on-ramp and off-ramp solutions. These vary significantly depending on the provider and their network solutions, but will often include integrations with local banks – as well as liquidity solutions to ensure the tokens can be converted into the currency required.

Above this are tools to ensure regulatory compliance, including KYC solutions very similar to, and in many cases the same as, those found in fiat-based products. Finally, the application layer, which takes the form of the app, software, interface or other means by which the customer interacts with the product.

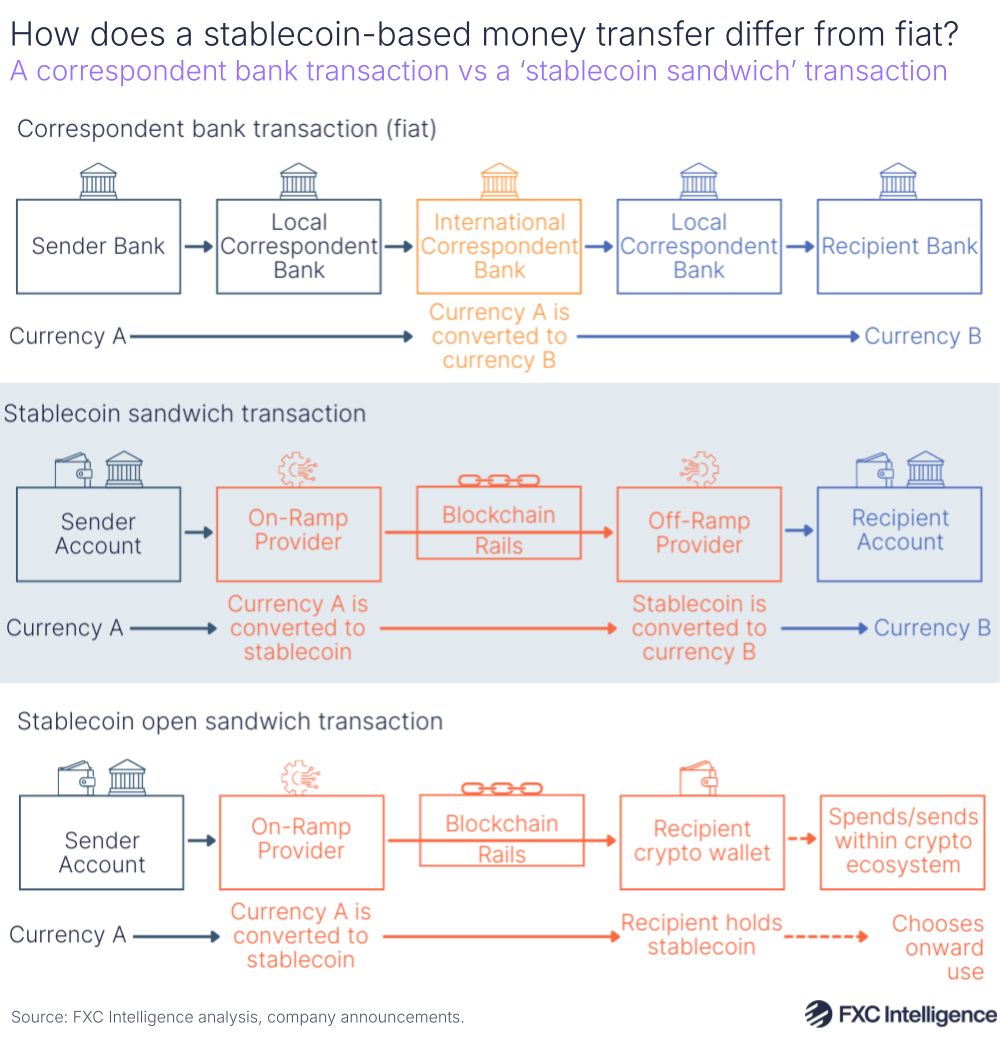

While there are some variations, the conventional approach to stablecoin-based cross-border payments takes the form of the ‘stablecoin sandwich’, a term widely credited to Fireblocks’ SVP of Payments and Network Ran Goldi in 2021.

While conventional correspondent bank-based transactions see a cross-border payment being moved through a chain of local and then international banks, with the currency conversion happening en-route, the stablecoin sandwich instead sees money converted from the sending fiat currency to a stablecoin, at which point it is moved internationally before being converted again to the recipient’s fiat currency.

This is particularly appealing in some markets as it reduces significant complexity in the correspondent banking system.

“For payments going into emerging markets, you might have six parties involved in any transaction,” explains Orbital’s Mason, giving an example of a cross-border payment to Colombia using the correspondent banking system.

“Say if my correspondent is Sberbank and they’ve got J.P. Morgan underlying that, there’s already three banks with a regulatory obligation in that chain and you might have three on the other side. Every one of those institutions will want visibility on that payment because it’s Colombia, and all the banks are open at different times of the day. So before you know it, your payment has been waiting there for two weeks and the people still haven’t got their money.”

This is particularly challenging if the payment is for perishable goods or other time-limited goods or services, and ultimately provides unhelpful friction for businesses in such markets that limits growth and presents a barrier to their ability to operate internationally.

The stablecoin sandwich replaces this potentially cumbersome chain, but it still requires those at either end of the payment chain to be willing and able to move money in and out of stablecoins at speed. This is something that was an initial challenge, but as stablecoin use has gained interest in different emerging markets, it has created increased local demand for stablecoins in those markets, increasing liquidity for such transactions.

“Even though the local banks in some of these markets are not particularly techy, we’re starting to see an increasing ability to do what we call an executable rate on a stablecoin sandwich,” adds Mason.

“If someone gives me euros, I automatically buy USDT in real-time with my European liquidity provider, sell that USDT in real-time in Mexico, then send Mexican pesos out through my Mexican banking partner. All that could take place in 5-10 minutes or even shorter.

“That is the golden egg in cross-border payments, in my view. It’s somewhat dependent on the capability in the emerging market, but everyone’s catching up.”

This ability to rapidly on-ramp and off-ramp payments from stablecoins is critical to effectively delivering payments at high speed and low cost, with the ‘last mile’ being particularly vital. However, it also means that those with strong foundations in the fiat world are well positioned to pivot.

“Because we come from the traditional finance side of things, we’ve already built that first and last mile of collection and disbursement of fiat rails, which still remain essential for the flow, and we’re now just able to leverage that new technology in the middle to speed up and rationalise the payment,” says OpenPayd’s Dimitrova.

However, while that last mile is key to stablecoin payments, it is not necessarily needed in every instance. As stablecoins broaden in utility, there is also increasing demand to be paid out in stablecoins, rather than converting back into fiat, with Fireblocks’ Shaulov reporting that the company has “started to see at least one of the sides of the sandwich disappear”.

Resulting in a transaction known as an ‘open stablecoin sandwich’, this is a process that some think will ultimately become dominant.

“The weird thing that people are going to have to get their head around is at some point people are not going to on-ramp and off-ramp anymore,” argues Mike Hudack, Co-Founder and CEO of Sling Money, a stablecoin-based consumer money transfers provider.

“It’s just going to be money on a blockchain. Nobody’s going to care anymore, and your Visa debit card is going to be powered by the stablecoin in your wallet or the tokenised deposit in your wallet.”

However, whether this will happen, and if so how soon, remains a matter of debate. While there is clear evidence that open sandwich transactions are in demand for some use cases, many do not see this moving to the whole market for the foreseeable future.

“For the next few years, the first and last mile fiat rail need will not disappear,” says Dimitrova. “The need for interoperability across fiat capabilities and stablecoins will not disappear.”

Stablecoins’ cross-border payments opportunity in data

Quantifying the current opportunity, or indeed size, of the stablecoin cross-border payments market is by no means easy, as while there is publicly ascertainable data for stablecoin transactions, it is much less clear which of those are specifically for cross-border payments.

Data from Visa and Allium shows that the total volume of all transactions conducted using all stablecoins across all blockchains reached $5.7tn across 1.3 billion transactions in 2024. 2025 is likely to be considerably higher, with H1 already reaching around $4.6tn across one billion transactions.

However, the vast majority of these are likely to be money movement for trading purposes, as stablecoins are popular as a stable store of value in between purchases of more volatile cryptocurrencies.

Individual players’ own reports provide a more defined picture of the market. BVNK, which is thought to be one of the largest players in the space, sees around $15bn in annual volume, according to Harmse, around half of which is in B2B payments, the largest segment for cross-border payments.

Meanwhile, Gertman reports Conduit’s annualised volume at $10bn, which the company believes is around 20% of the global B2B market for stablecoin-based cross-border payments, while Orbital reports an annualised run rate of $12bn.

Cross-border payments’ stablecoin TAM

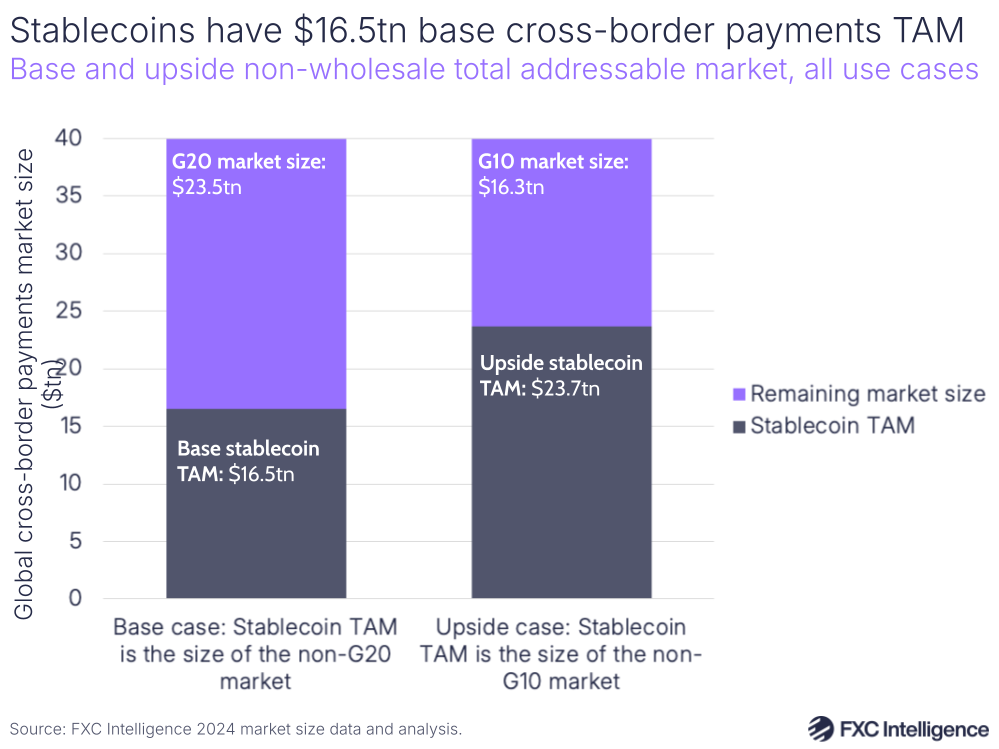

Previously published cross-border payments market size data from FXC Intelligence shows that the estimated size of the entire cross-border payments market in 2024 was $194.8tn including wholesale, while non-wholesale payments alone totalled $40tn.

It is likely that the current total cross-border payments market using stablecoins is still in the billions, meaning that is likely to account for less than 1% of the entire market at present. However, its total addressable market (TAM) is considerably higher.

“When we’re talking about a stablecoin market cap of around $250bn – that’s nothing,” says Paxos’ Kendall. “When we see this thing go, I suspect it’ll be more with potentially regulated players like ourselves working with institutions that move trillions of dollars.”

In order to define the cross-border payments TAM for stablecoins, we need to draw on the regions that companies are reporting flows in: emerging markets.

“The largest margins worldwide are now at that point where funds are going from the developed world into emerging markets; out of emerging markets; or from emerging markets to emerging markets,” says Orbital’s Mason.

“Transaction banking is making a fortune on some of these. Charges are quite opaque and the speed of payment can be a real problem.”

This opportunity is also reflected in Fireblocks’ own experiences, with Shaulov reporting that the main regional corridors the company is currently serving are into and out of Latin America from the US and Europe; into and out of Africa from Europe and “some US”; and between Asia-Pacific and the US and Europe.

Based on this, it is reasonable to frame the main opportunities for stablecoins as being in the markets outside the G20, and to a lesser extent the G10, which consists of Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the US. As a result, we see the non-G20 market as the base TAM, while the non-G10 market serves as the upside case.

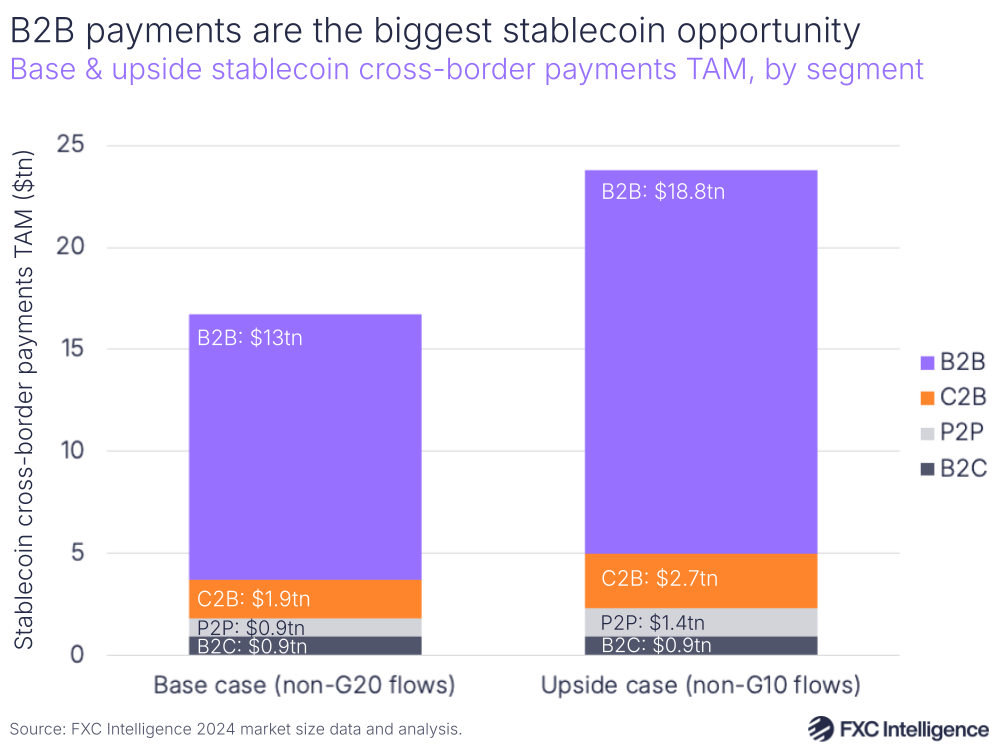

On this basis, the base stablecoin cross-border payments TAM currently sits at $16.5tn across all verticals, equivalent to 41% of the non-wholesale market, while the upside case is $23.7tn, or 59% of the non-wholesale market.

Looking by segment, the B2B use case is by far the biggest opportunity, as it is in fiat-based cross-border payments, although the differences between the G10 and G20 do make for some key differences between the base and upside case.

China, which is part of the G20 but not the G10, is a top-sending country for all use cases, making it a key contributor to the upside case, but there are others that disproportionately increase the TAM of some verticals. Person-to-person (P2P) payments, for example, has the biggest gap between the base and upsize case because the G10 does not include key P2P senders in the G20, which alongside China includes Saudi Arabia, Russia, the UAE and India.

However, while emerging markets represent the primary TAM for now, this may not be the case forever, with some players such as BVNK reporting a small contribution from other markets too.

“We see East-to-West flows because it’s difficult to send money from Hong Kong to the US sometimes, even though financial infrastructure works really well,” says BVNK’s Harmse. “A lot of our volume is B2B payments between businesses around the world, and there’s not necessarily always an emerging market in there.”

How can FXC Intelligence’s market sizing data help frame my market opportunity?

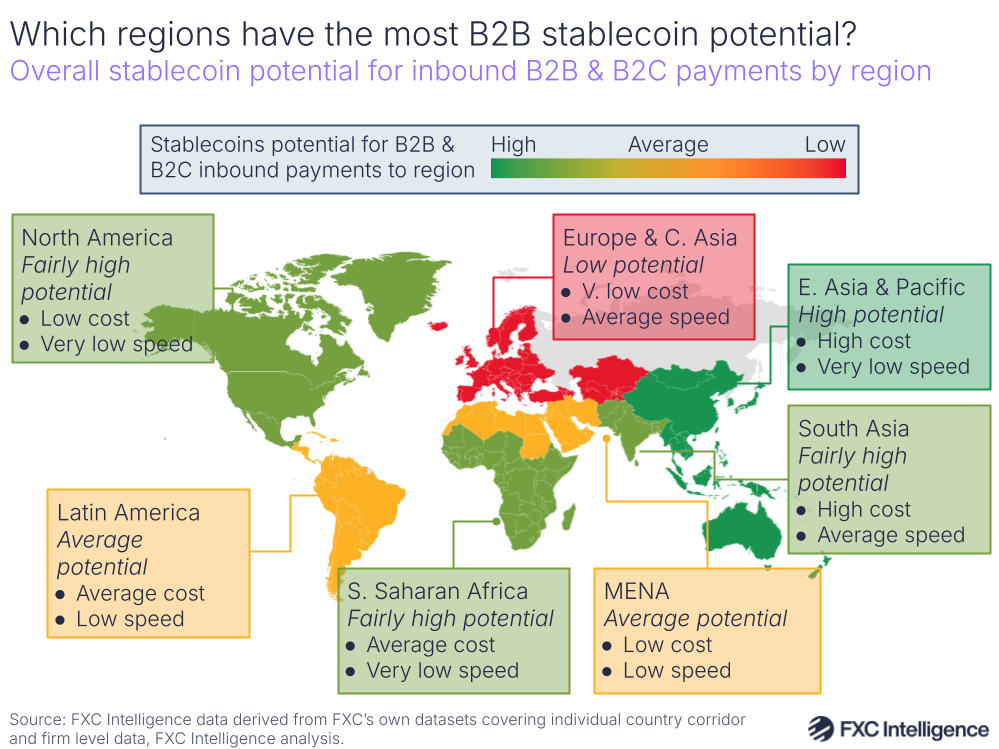

The regions with the highest stablecoin potential for P2P payments

While this provides a sense of the opportunity at a global level, there are also regional cuts that show a greater sense of where the cross-border payments opportunities are for stablecoins.

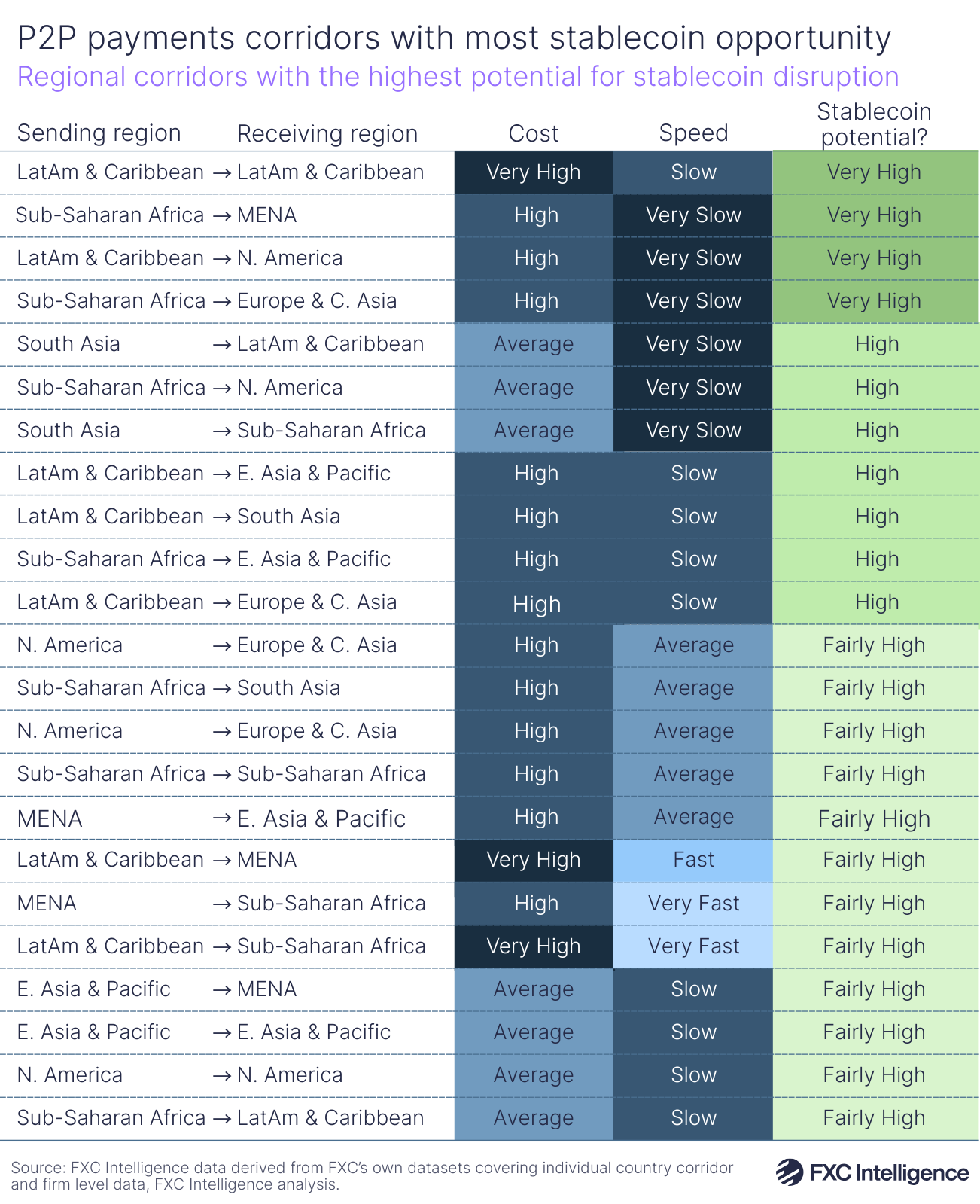

As part of its supply of retail pricing data for the Financial Stability Board’s Annual Progress Report on Meeting the Targets for Cross-Border Payments, which is used to monitor progress against the G20’s cross-border payments roadmap, FXC Intelligence produced data on the average speeds and costs for a number of payment types across regional corridors globally. Mapping these based on price and speed enables us to determine which corridors provide the greatest opportunity for stablecoin-based payments.

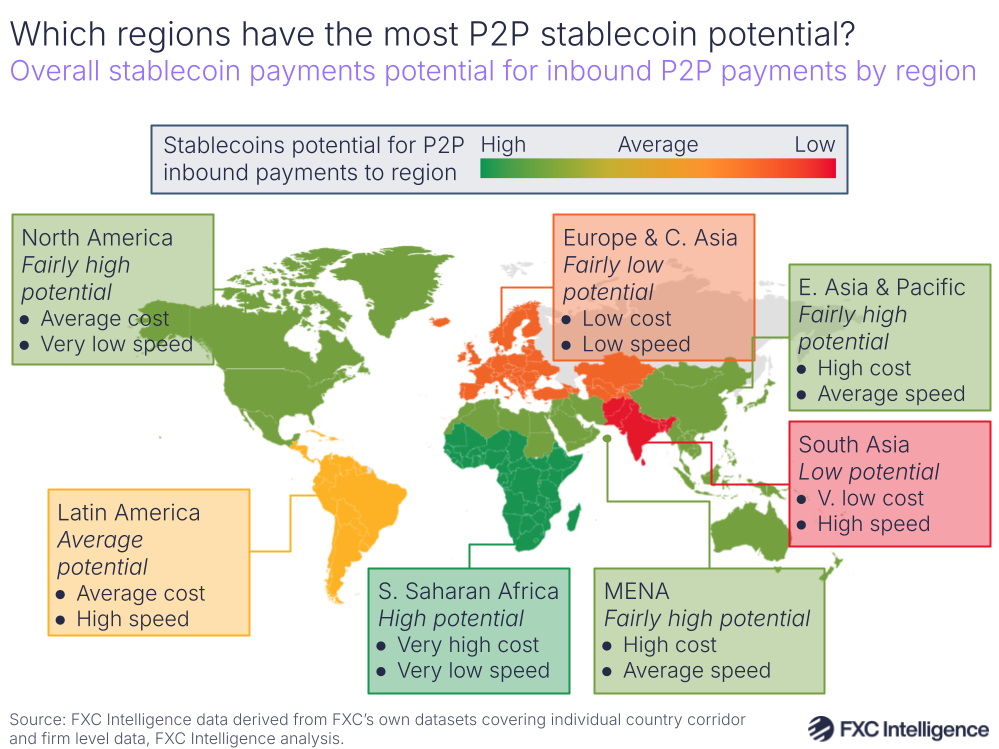

On the P2P side, sometimes referred to as consumer-to-consumer (C2C), there are a number of regions that particularly stood out as presenting a strong opportunity for stablecoins due to their combination of high average costs and slow average speeds.

This included cross-border payments sent within Latin America and the Caribbean, alongside those sent from Sub-Saharan Africa to the Middle East and North Africa (MENA); Latin America and the Caribbean to North America; and Sub-Saharan Africa to Europe and Central Asia.

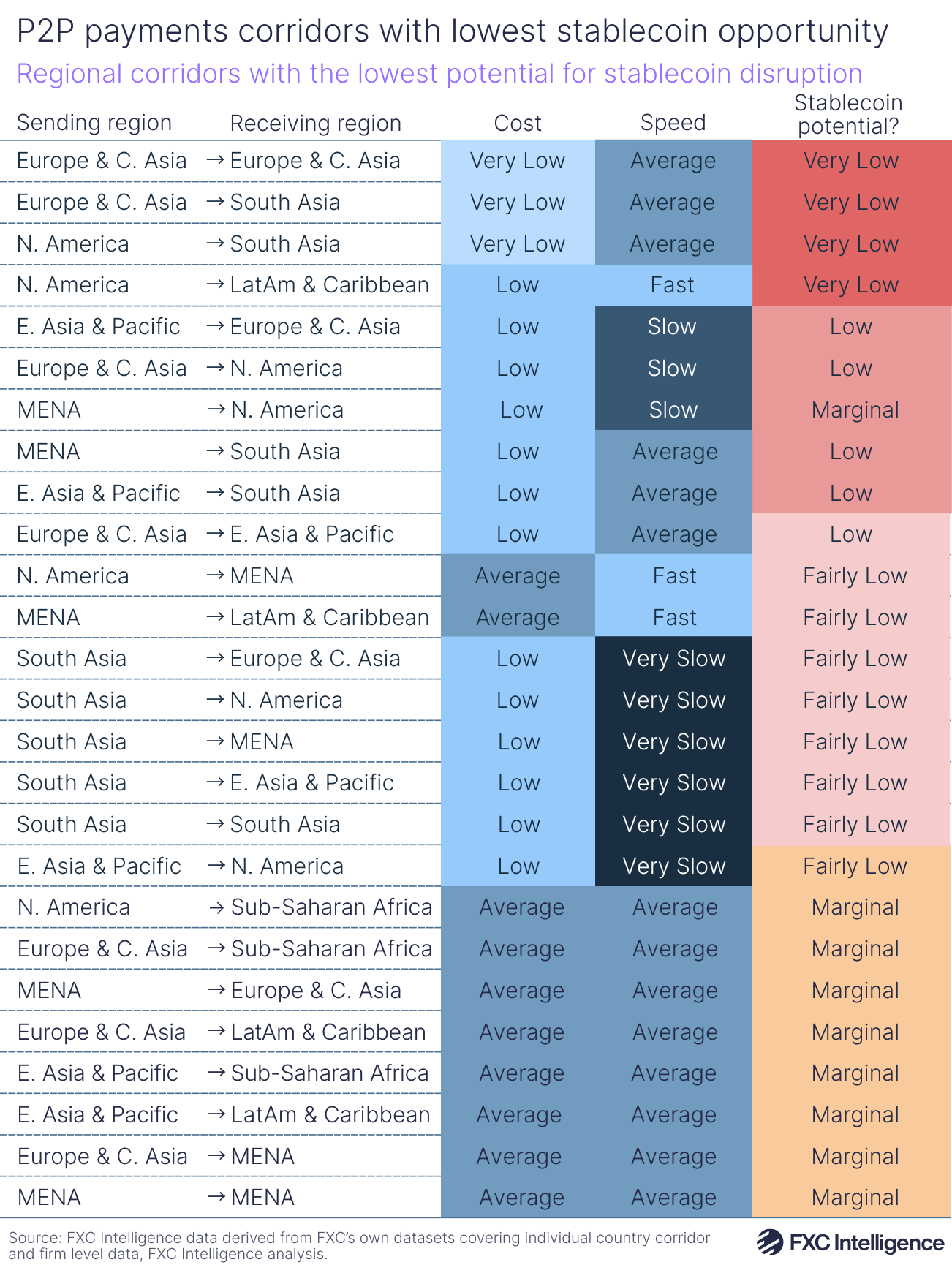

However, there are also corridors where P2P payments have far lower potential for stablecoins at present, as a result of low or very low costs and average or fast speeds.

Here, cross-border payments sent within Europe and Central Asia saw the least potential, alongside those sent from Europe and Central Asia to South Asia and payments sent from North America to either South Asia or Latin America and the Caribbean.

Looking at global average sends into each region, Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest potential overall, with very high average costs and very low average speeds, while South Asia had low stablecoin potential for inbound P2P cross-border payments.

The regions with the highest stablecoin potential for B2B payments

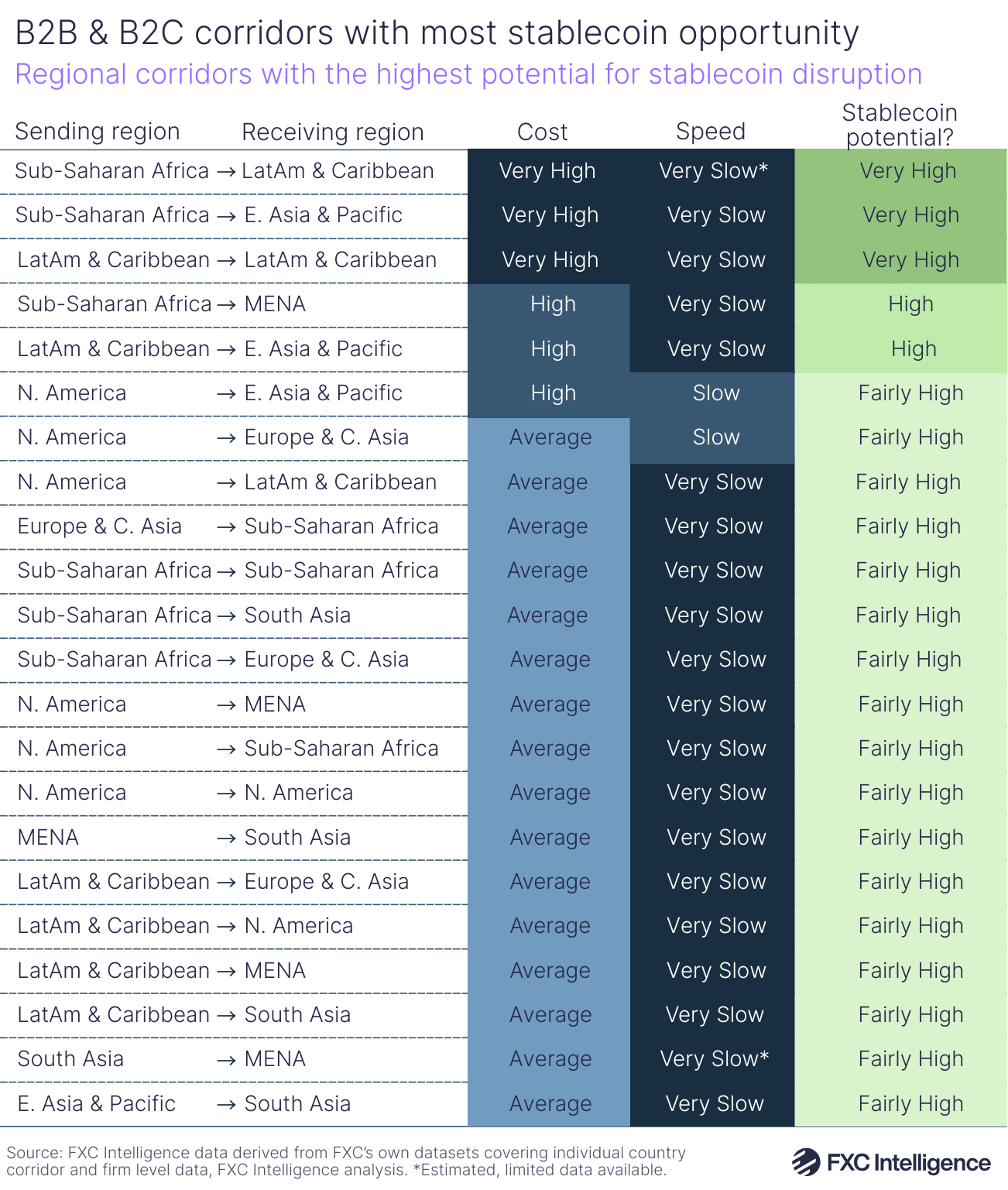

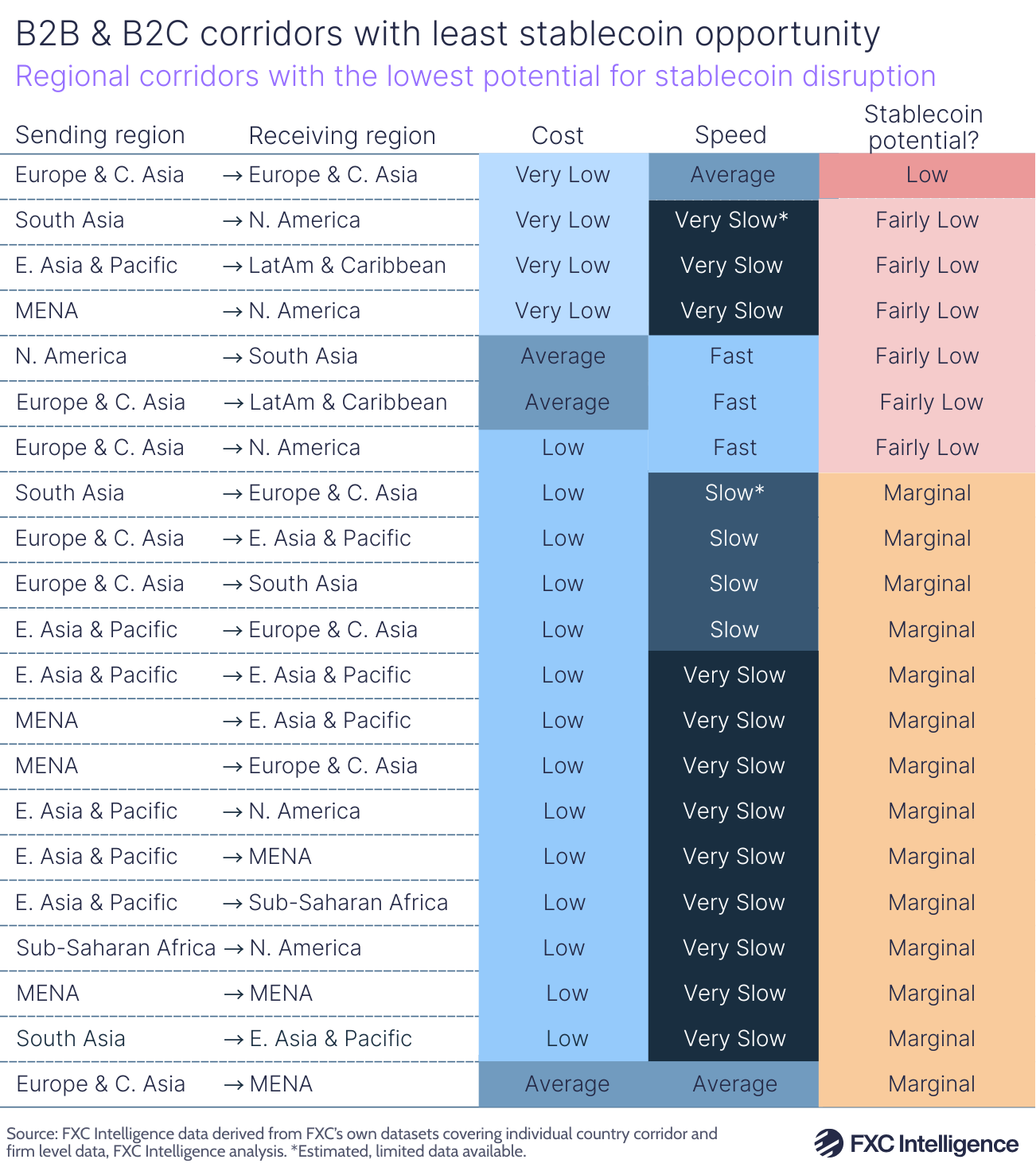

Looking at combined data for B2B and B2C payments provides a slightly different picture, however, as use cases can result in quite different costs and speeds, depending on the corridor in question.

Here, the regional corridors with the highest potential for stablecoin-based cross-border payments are Sub-Saharan Africa sending to both Latin America and the Caribbean and East Asia and the Pacific, as well as intra-Latin America and the Caribbean.

Meanwhile, there were few regional corridors with very low potential, with payments sent within Europe and Central Asia seeing the lowest opportunity. Those sent between South Asia and North America, as well as those from East Asia and the Pacific to Latin America and the Caribbean and MENA to North America also saw fairly low potential.

On a global basis, Europe and Central Asia has the lowest current potential as a receive market for B2B and B2C cross-border payments using stablecoins, although there are likely to be some country-level exceptions to this.

By contrast, East Asia & Pacific saw the highest average potential as a receive market, due to a combination of high costs and low speeds.

Which corridors and use cases should I be focusing my stablecoin strategy around?

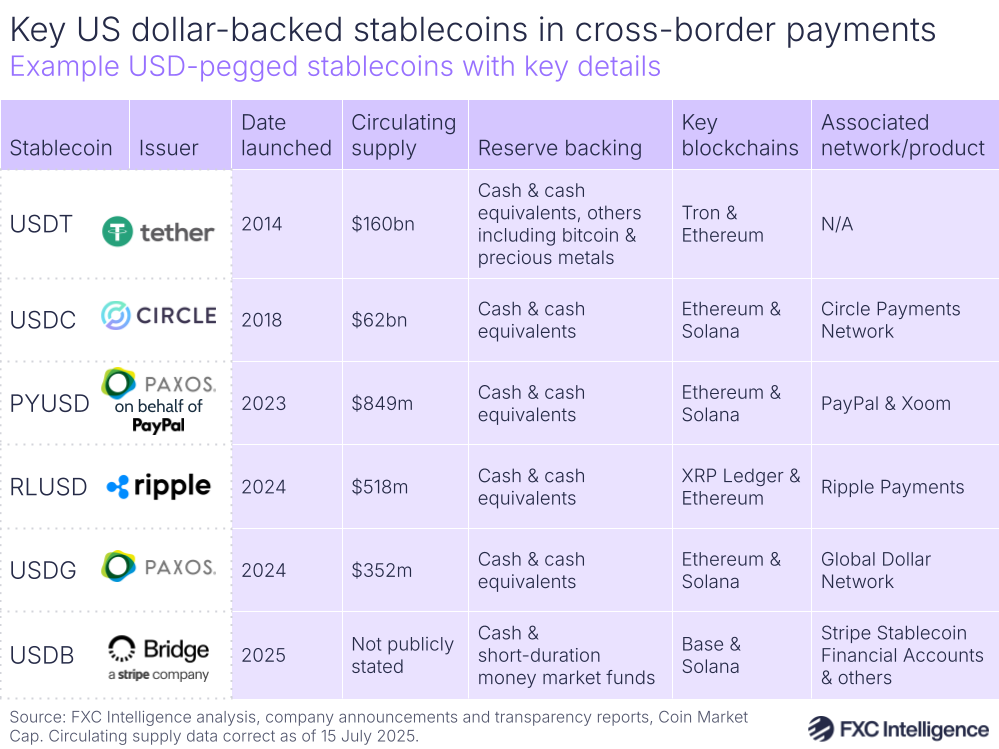

Key stablecoins: USDC, USDT and beyond

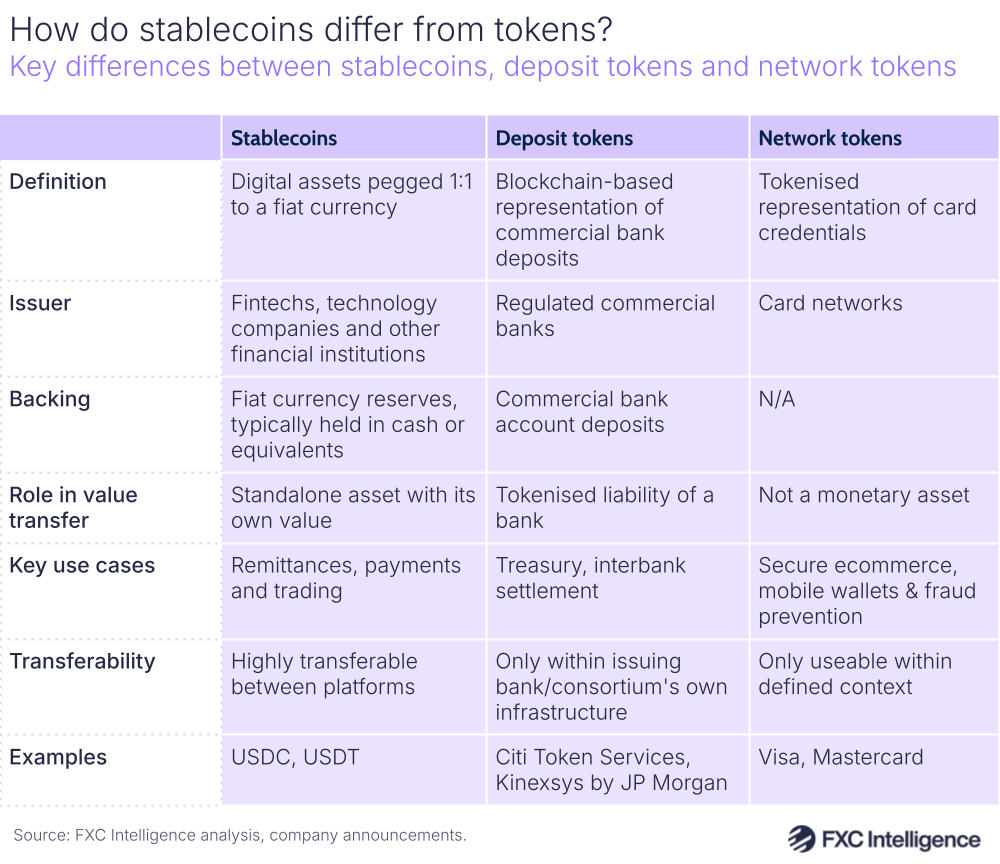

While there are myriad stablecoins available to buy, hold and trade for crypto users, not all of them have utility for cross-border payments. Part of this is their design, including the nature of their reserves and the level of transparency they provide, but there is also the matter of the volume of that stablecoin, and whether it can be reliably integrated into automated technological processes without issue or the ability to exchange them for the required currency.

“The two things that really are important for stablecoins are liquidity – enough people in different currencies – and APIs that don’t go down,” says Higlobe’s Farman-Farmaian.

Different needs and applications have prompted different players to develop their own stablecoins and, among those focused on cross-border payments-related applications, the overwhelming majority are pegged to the US dollar. The most notable of these are Tether’s USDT and Circle’s USDC, which are the two biggest stablecoins on the market, but there are also other stablecoins with smaller circulating supplies – the total number of that stablecoin that has been issued – that are also notable due to the companies behind them.

PayPal’s stablecoin PYUSD is smaller but has seen steady growth in part due to the ability to use it across a variety of PayPal’s products, including its Xoom remittance brand and to pay for products at PayPal branded checkouts.

Ripple, meanwhile, launched its stablecoin RLUSD last year largely to use on its proprietary blockchain rails, which have long underpinned its cross-border payments offering via its crypto XRP.

The most recent additions are Paxos’s Global Dollar (USDG), a stablecoin launched by the company’s Singapore arm in November that is designed to comply with various international frameworks for stablecoins and form a core part of its recently launched stablecoin payments network the Global Dollar Network.

Finally, Stripe’s Bridge has also entered the stablecoin issuing arena with the launch of USDB, which will be used within its own cross-border payment network solutions. Crucially, unlike the others in this group, USDB is not available to trade by retail investors, and will serve only as an internal token for Bridge.

Which stablecoins dominate the market?

While there are many stablecoins even within the payments world, USDT and USDC account for the overwhelming majority, at more than 80% of the entire market capitalisation.

USDT does remain significantly larger, which makes it a key option for some providers, but USDC is significant enough in size to be the go-to option for many players. Crucially, there are also some differences in the two coins’ reserves that can cause some hesitancy, with USDT including some unorthodox assets among the minority of its reserves, including bitcoin and precious metals, while USDC’s reserves are held only in cash and cash equivalents in US-domiciled banks.

This, along with the offshore location of its reserves and lower cadence of transparency reports has led some US-based financial institutions to be very reluctant to touch USDT, although many in the industry have no issues using it and the size of its circulation makes it necessary for some use cases.

“I personally think Tether easily has enough funds to prop that coin up every minute of the day,” says Orbital’s Mason.

Meet the rails: The different blockchains

While stablecoins are the core part of the technology, the rails they move on are also critical, as different blockchains have different capabilities that can impact how well suited they are for payments.

For Circle, whose USDC is designed to be used in myriad ways beyond just cross-border payments, there has been a strong focus on ensuring native support on a wide range of blockchains, with the current total standing at 23.

“We have this incredible infrastructure that allows us to issue stablecoins on all of these chains and manage their liquidity across these chains,” says Circle’s Chandhok.

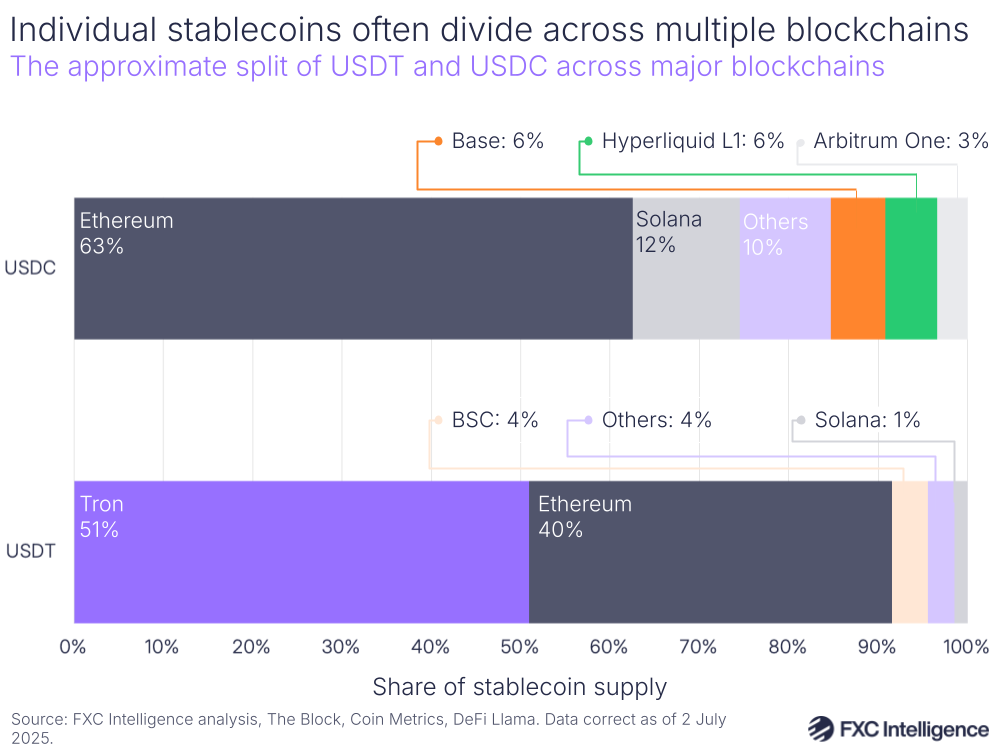

However, despite this broad availability, the majority of its circulation is concentrated on a relatively small number of blockchains, with the Ethereum blockchain accounting for 63% of the market and the next largest share, held by Solana, accounting for just 12%.

USDT also has a strong presence on Ethereum, where around 40% of its share resides – while this is lower than USDC’s split, USDT’s larger overall circulating supply means there is in fact a greater supply of USDT on the blockchain.

However, TRON accounts for around 51% of USDT’s market. While Circle did previously mint stablecoins on TRON, it opted to transition off the blockchain in early 2024, citing regulatory and compliance concerns.

While companies using a specific stablecoin for cross-border payments are not automatically limited to a single blockchain, they are likely to opt to work with a relatively limited number as each one not only requires its own integration into their systems, but has its own behaviour and standards, potentially creating friction in the process if stablecoins have to be moved between different blockchains.

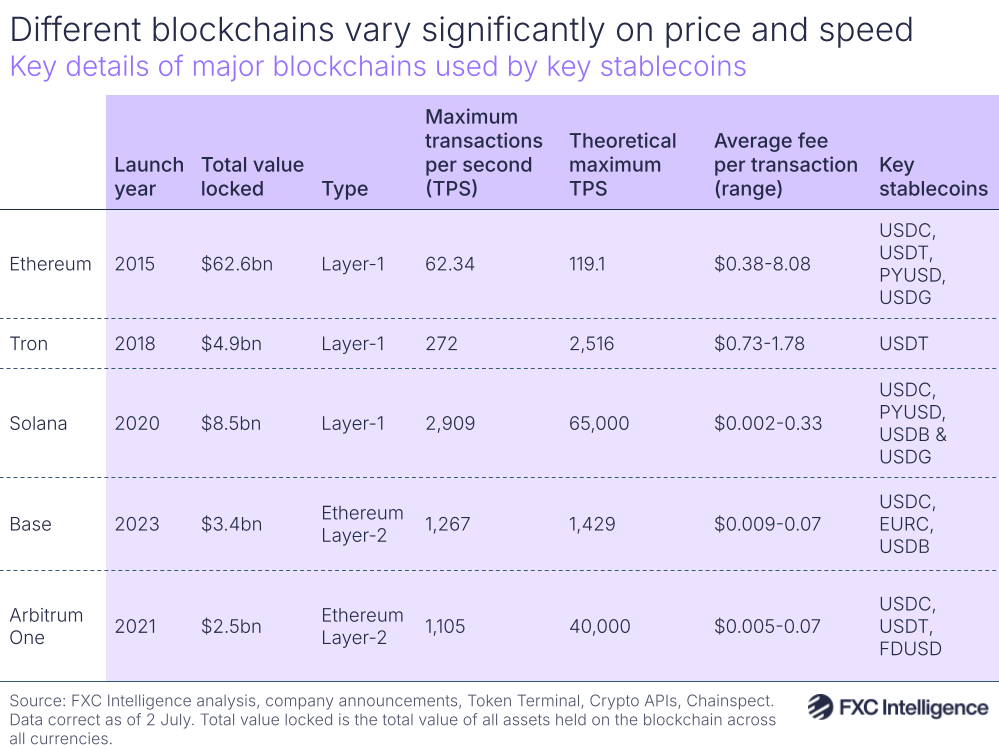

Among blockchains popular with key stablecoins for cross-border payments, there are two main types: Layer-1 and Layer-2. Layer-1 blockchains are the base blockchains, while Layer-2 variants are built on Layer-1s, typically to increase speeds and reduce costs.

In terms of total value locked, i.e. the value of all forms of digital currency held on each blockchain, including both stablecoins and non-stablecoin cryptocurrencies, Ethereum is the largest by some way, followed by Solana. However, there is a notable difference between the number of transactions they can handle, as well as the amounts that can be charged per transaction.

Ethereum has a relatively slow number of transactions per second (TPS), having reportedly achieved a maximum of around 62 TPS, and having a theoretical maximum TPS – a measure that provides a ballpark top end, but which is unlikely to be truly reached in reality due to frictions – of around 119.

By contrast, Solana’s maximum achieved TPS is around 2,900, though its theoretical maximum is thought to be much higher, at around 65,000. To put this into perspective, in its fiscal year 2024, Visa saw average transactions per second of around 9,600.

There is also a very pronounced difference in the cost of moving money across the two blockchains. Average prices vary significantly, meaning that a company’s base costs can shift depending on the time or day.

Data from Token Terminal shows that Ethereum’s average transaction fee, often known as a gas fee, has ranged over the past year from just under $0.4 to above $8, while Solana’s has been only slightly above $0.03 at its highest, and a fraction of a cent at lowest.

While Ethereum is relatively expensive and has a low transaction cap, its token standards are widely supported, meaning that there is a demand to move money on a variant of it, if not the Layer-1 blockchain itself. As a result, multiple Layer-2 blockchains have been developed on Ethereum, including Base and Arbitrum-One, both of which have a much higher maximum TPS and much lower average transaction fees, as well as a variety of other payments-friendly features, making them appealing options for some providers.

How key stablecoins are evolving in use

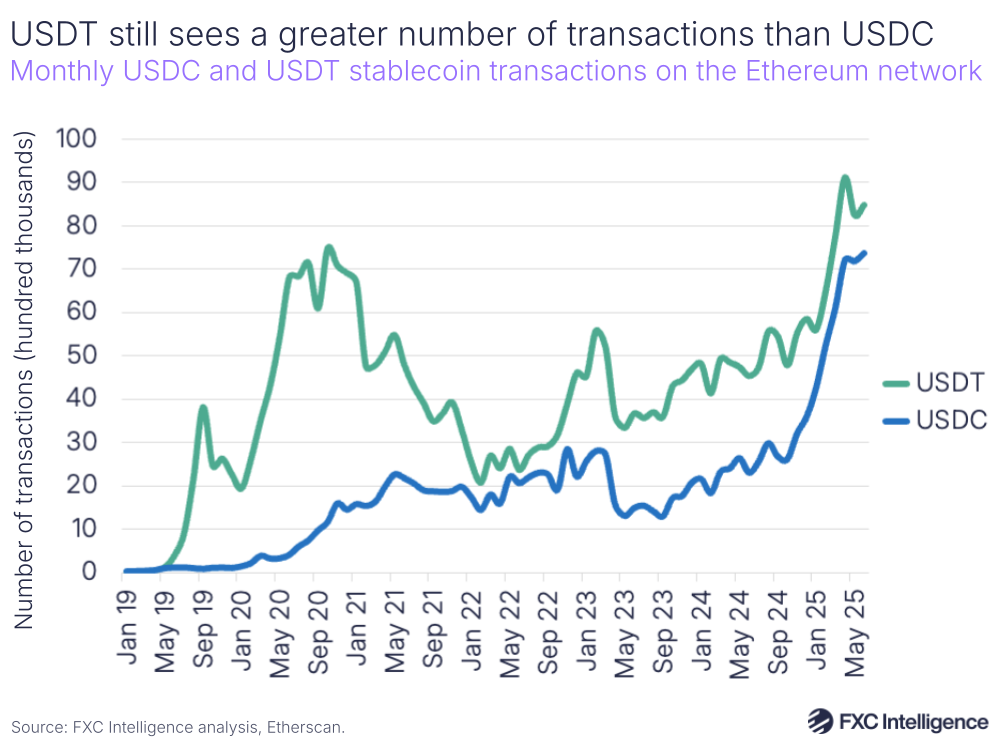

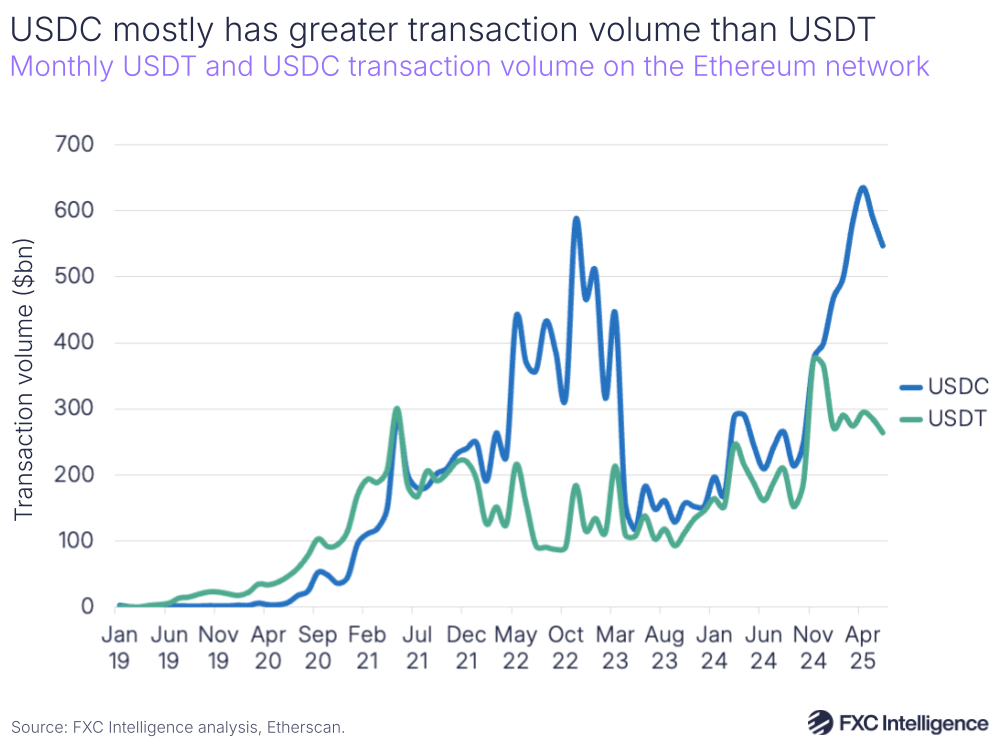

While USDT is larger than USDC in terms of supply, transaction data from the Ethereum blockchain does show some variations that speak to differences in how the two stablecoins are used.

Despite the supply of USDT on Ethereum being more than 60% higher than the supply of USDC on the blockchain, the number of transactions of the two are far closer in number, with USDC sitting only slightly below USDT since late 2024.

Meanwhile, the transaction volume – i.e. the amount of value that is being transacted on the blockchain in each stablecoin – has actually been higher for USDC than for USDT since November 2024, with the gap having widened significantly across the first half of this year.

It is not clear what is driving this, and there are likely to be a number of factors, but it is possible that increased interest in stablecoins among the payments industry, many parts of which have a strong preference for USDC, is playing at least a partial role.

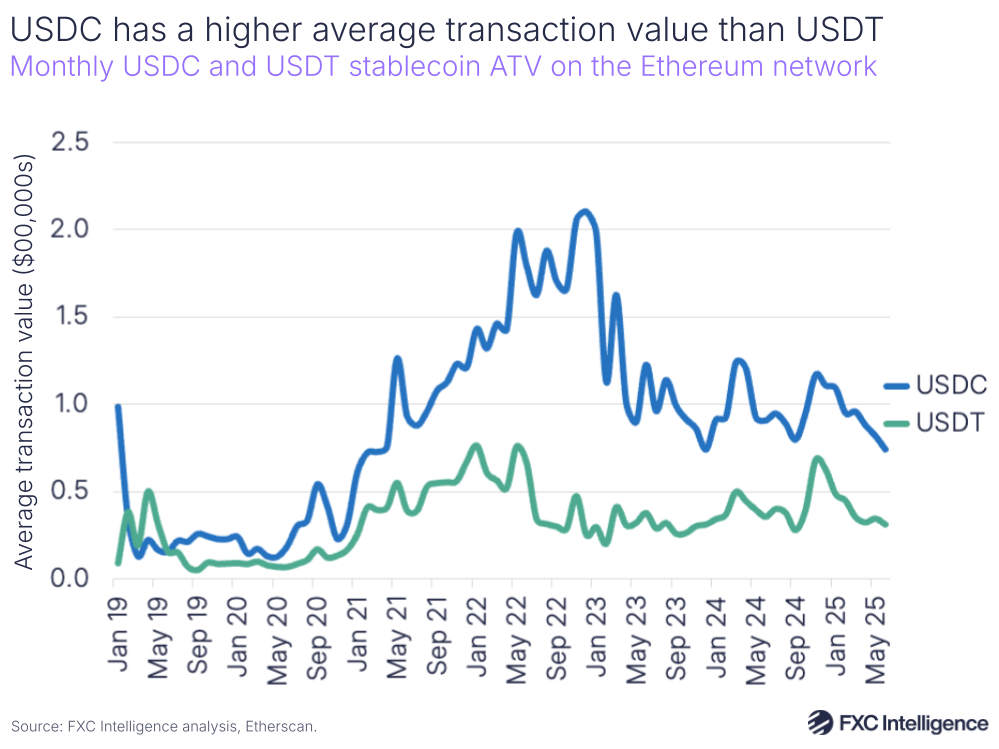

What is notable is that the average transaction value for USDC has been consistently higher than that of USDT since 2020, indicating that it is being favoured more to move large amounts, at least on the Ethereum blockchain.

This does not mean that USDT is not used to move high monetary values – the average transaction value for both is in at least the tens of thousands of dollars – but it does speak to a difference in typical use cases for the two stablecoins.

Cross-border payments’ key stablecoin players

Building a picture of the key players in the cross-border payments space is a complex task, as there are a vast number of companies operating in the sector. Many more are appearing at the smaller end of the market on a regular basis, while growing numbers of fiat-focused players – often referred to as ‘tradFi’ players by those in the blockchain/Web3 space – are also integrating the technology.

We have attempted to capture the shape of the current market in the map below, which is not intended to provide an exhaustive look at every player engaging in stablecoins, but to highlight key players both big and small who are active in the sector.

While many companies operate across multiple aspects of stablecoin cross-border payments, including BVNK, Fireblocks and Bridge, there are a number of key segments that divide offerings within the industry. These include companies issuing their own stablecoins, or providing white-label issuing services to others.

Meanwhile, there are also a growing number of players providing white-label payment services, also sometimes referred to as B2B2X services, to others in the industry. Varying between those offering entire turnkey networks and those whose solutions augment mainstream payment providers’ wider network maps, these solutions are not aimed at the end user, but rather to power the payment solutions of other players.

Beyond this, there are also a relatively large number of companies offering B2B payment services using stablecoins directly to businesses, although there is notable variation in the scale of the companies among their client base. There are also those providing payroll and contractor pay-outs, as well as providers of related services to freelancers in receipt of such payments, and there are also, inevitably, those catering to the consumer money transfer end of the market.

While there are many focused on delivering money to people using stablecoins, there are also those on the payments acceptance side, with a wide range of organisations focusing on providing the ability to accept payments in stablecoins as well as smaller numbers offering issuing solutions for both stablecoin cards and digital wallets.

Key opportunities and use cases

While emerging markets represent the key focus for opportunities in stablecoin cross-border payments, the wide range of types of players is a reflection of the broad range of use cases that have begun to emerge, some of which have arisen from each other.

Instant settlement

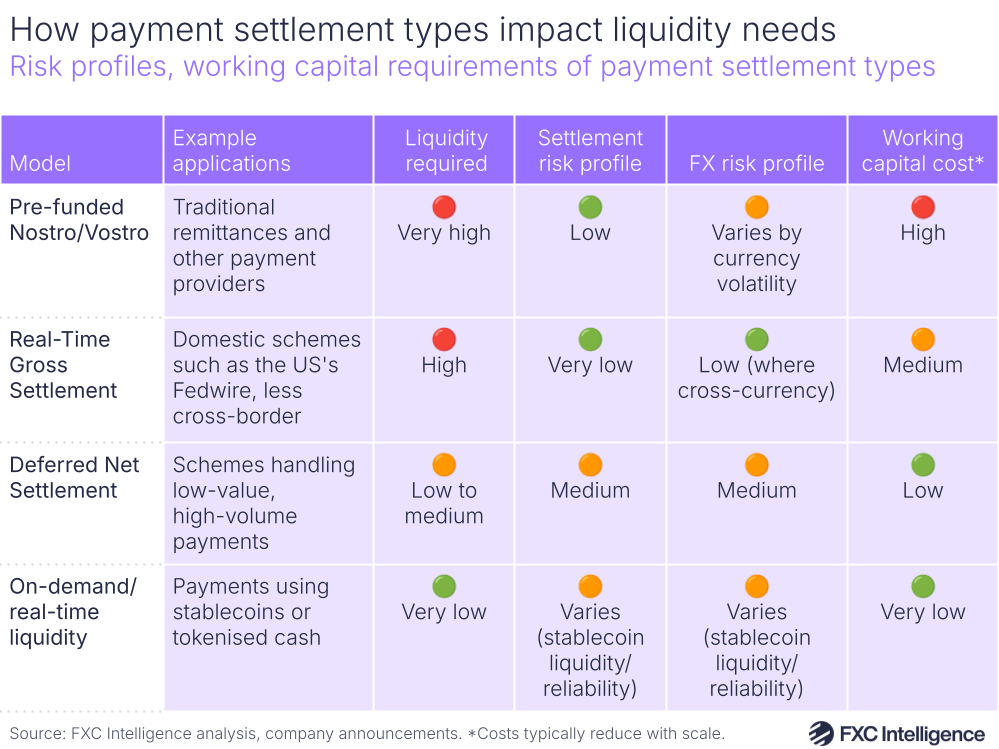

While there are many areas where stablecoins present a benefit, instant settlement is one that was consistently raised by many of the people interviewed for this report, mainly because it sits in stark contrast to common approaches to managing settlement in cross-border payments.

“What incumbents are doing today to create instant payments is having liquidity on both sides,” explains Conduit’s Gertman.

“If you’re sending payments today from Brazil to Europe, that payment may appear very quick to you as a customer. But under the hood, what actually happens is there’s a bunch of euros sitting in Europe waiting to be distributed to customers or an overdraft facility with a bank in Europe.”

This method, which is commonly used by traditional remittance players, typically relies on pre-funded nostro and vostro accounts. These are accounts held in a foreign currency at a correspondent bank, referred to as nostro by the domestic bank and vostro by the foreign correspondent holding the account.

“Pre-fund is a massive problem in payments and has been for the last 25 years,” says BVNK’s Harmse, characterising it as “a technology problem” that has not been meaningfully addressed.

One alternative that has gained recent popularity is netting, where settlement for multiple transactions is handled together, with companies only having to cover the difference between the volume of payables and receivables. This can significantly reduce the amount of funds companies need to have on hand to operate, however stablecoins take this a step further by settling each transaction instantly.

“You don’t have to estimate liquidity on the other side, you don’t have to estimate demand, you just do the transaction because fundamentally party A in country A is sharing a common ledger with party B in country B,” says Circle’s Chandhok.

This is proving to be a significant benefit to companies operating in the space, as it has the potential to reduce the working capital required to operate.

“With instant settlement, instead of having a million dollars tied up, I can have $10,000 because the guys at Mastercard know they can pull my money instantly from my account,” explains Higlobe’s Farman-Farmaian. “We have zero working capital out there.”

While this has significant potential benefit for those operating in the space, Farman-Farmaian also sees it having a significant knock-on effect as more players adopt the model.

“Trillions of dollars that are currently tied up pre-funding accounts around the world are going to be freed up in the next five years,” says Farman-Farmaian.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen to that money, but if the market is exponentially more efficient, real financial innovation can occur.”

However, there is also a potential downside to instant settlement that may prompt hesitation for some, in that the lack of delay removes the ability to reverse a transaction during the process.

“When Swift got hacked, 80% of that was rolled back because it took three days and the analysts of Deutsche Bank figured out that you can roll it back,” says Fireblocks’ Shaulov.

“But if you lose control over a wallet that has stablecoins or you remitted the transaction to the wrong destination, it’s likely that you won’t be able to roll back because you have instantaneous settlement or instantaneous finality, the flip side is if the finality is into the wrong hands, then you can’t roll it back.”

Meanwhile, while the lack of a need for reserves has led some to embrace stablecoins as a treasury solution, including MoneyGram, not everyone is convinced at this stage. For example, while Wise is watching the technology, it is not currently using stablecoins in its treasury management.

Dollar proxies and hold ability

While instant settlement is not particularly market-specific, one use case for stablecoins that has arguably been one of its biggest adoption drivers is that they are, at least in the case of USDC or USDT, essentially a digital form of dollar. And because they are not dollars themselves, they can often be more easily held by people around the world looking for alternatives to their volatile local currencies.

“If you’re a person in Argentina, you don’t really want to hold Argentinian pesos. You may not be able to hold US dollars because of local laws, but you want to be in the US dollars, so they’re going to be a holder,” says Orbital’s Mason, one of a number of companies to give the region as an example.

Turkey is also a market cited by many for this use case, and with good reason: it is thought to have the highest rate of stablecoin ownership per capita in the world, with 2024 research by Chainanalysis finding purchases in the country amounted to 4% of its GDP.

“Turkey has high inflation, and so people get paid and they want to move straight to dollars,” says Paxos’ Kendall.

“It’s very expensive to get it from the banks, and quite difficult, so they get it from Tether. But they don’t know that it’s Tether, it’s just a cheaper dollar that they keep in their crypto wallet rather than their bank.”

He characterised stablecoins as “democratising access to an almost unlimited demand for dollars”, a view echoed by Circle’s Chandhok, who described having access to dollar banking as “a superpower”.

“People in the West don’t understand that,” he adds. “For a lot of these businesses, especially in the cross-border space, getting dollar banking is very hard, getting competitive FX is very hard. Crypto markets like dollar stablecoin swaps and on-ramps and off-ramps around the world solve that problem for them without having to rely on traditional banking.”

However, hand-in-hand with this has been another factor that has helped accelerate demand further, in the form of the remote services professional, a market that emerged during the Covid-19 pandemic in response to the rise of remote working.

“A new market was created of highly paid individuals who lived overseas, who were not wealthy Europeans or Americans cruising the world and working, but the most educated local people working for American and European companies and earning an in-between salary much higher than the local salary, but not earning an American salary,” says Higlobe’s Farman-Farmaian.

His company offers USD receiving accounts to contractors and businesses in key emerging markets, but crucially retains the value in stablecoins up until the point where the user wants to spend it, at which point it is instantly converted and paid out using the local payment network, such as Pix in Brazil.

“It’s like having an ATM in the sky. The money is always available whenever she wants it, instantly,” he explains, adding that this instant availability, rather than having to withdraw to local currency in monthly batches, changes the user’s “whole relationship with money”.

The desire to hold money in stablecoins doesn’t just sit with individuals, however. For emerging markets businesses regularly engaging in cross-border transactions, retaining the funds they receive either partially or fully in stablecoins can also be appealing.

“Some companies will just want to work in a USDT or USDC world,” explains Orbital’s Mason.

“They don’t want Mexican pesos, they’d rather sit with the stablecoin because then they’ve got to pay somebody else, or they only want to convert a proportion of it because that’s what they need to pay their workers.”

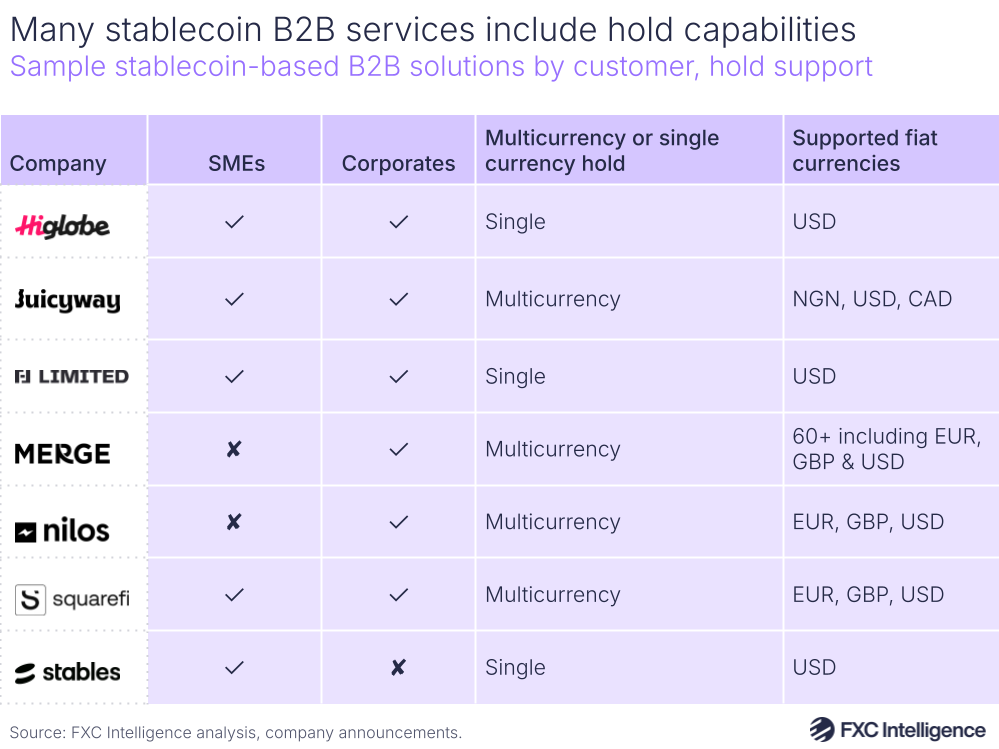

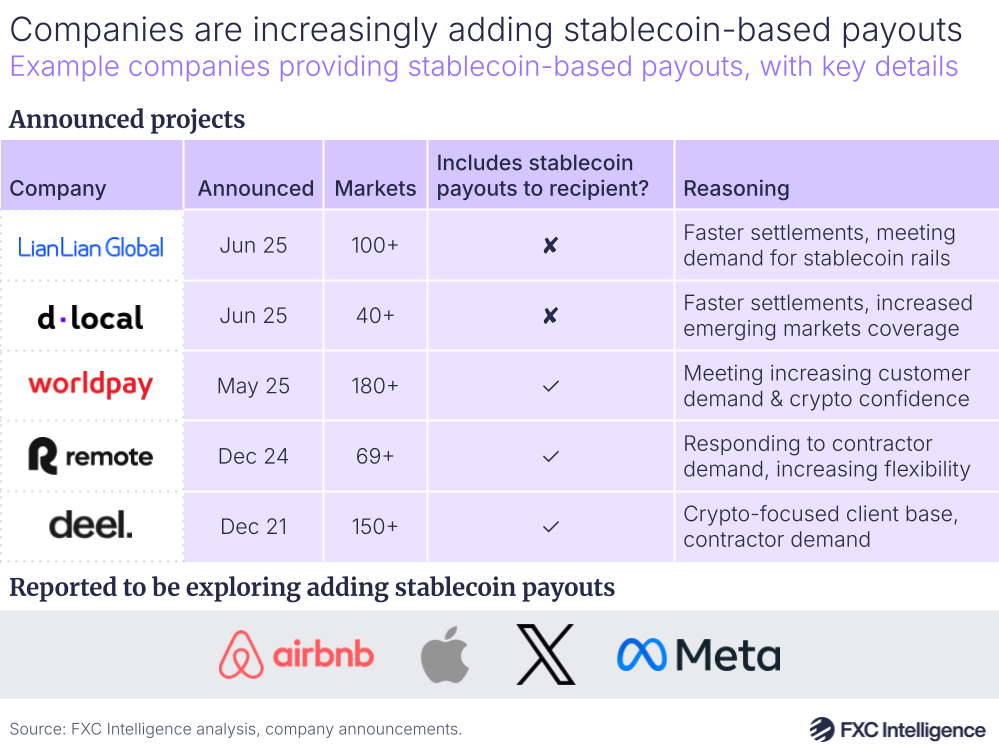

Stablecoin pay-outs

On the flip side of this growing demand to hold stablecoins in dollars is the ability to make cross-border pay-outs in stablecoins, which Fireblocks’ Shaulov says is currently “a pretty prevalent use case”.

“Say you have IT contractors in Colombia that are working for European or American companies. They prefer to be paid in stablecoins rather than some form of a local wire,” he explains.

Growing numbers of marketplaces and payment service providers have added stablecoin payments to their stack with Worldpay, one of the world’s biggest pay-outs businesses, recently adding the capability.

“It’s really been merchant demand driving PSPs to look at, ‘hey, what do we have in our pay-out stack?’,” explains BVNK’s Harmse, adding that growing use of stablecoins in emerging markets has been a key driver of this increased interest.

“Now you’ve got this new payments technology that users in emerging markets are asking for, whether it’s a gig economy platform looking to get paid out, or it’s a marketplace looking to pay out users or sellers.”

While there are a variety of use cases for pay-outs, Triple-A’s Barbier sees the payment of content creators having particular potential with stablecoins.

While there are a variety of use cases for pay-outs, Triple-A’s Barbier sees the payment of content creators having particular potential with stablecoins.

“The beauty of stablecoins is that they make it economically viable to send even tiny amounts,” he explains. “For example, a gamer or content creator earning just one dollar can actually receive it – because with stablecoins, the cost of transferring that dollar is negligible.”

Trade finance and B2B payments

Pay-outs may be attracting attention, and it certainly provides significant potential for many in the space, but in terms of pure flows it pales in comparison to B2B payments.

“B2C probably gets disproportional air time, but the flows are actually happening on the B2B side,” says BVNK’s Harmse.

Here, adoption has again been a knock-on effect, with one use case in a market begetting others. Conduit’s Gertman points to import-focused emerging market businesses opting to hold in stablecoins to avoid FX restrictions associated with fiat dollars, but then looking to use that stablecoin-based balance of payments for further transactions.

“That’s what we’re providing for them and they become very excited because otherwise, sending this payment to China, for many countries across the world, it takes three, four, five, I’ve seen as many as seven business days,” he says. “Instead of that you can send from your stablecoins, you can essentially send within minutes. Maybe not literally instantly, but very quickly.”

Fireblocks’ Shaulov also cites this increase in locally held stablecoins as having been critical to driving B2B cross-border payments activity using the technology.

“Now that you have enough stablecoins in Colombia, you have an importer that is importing something from Hong Kong, and the way that they will mobilise sending the money will be that the exporter in Hong Kong or in China will prefer to get USDT,” he says.

“Buying peso USDT in Colombia is actually cheaper because of the incoming flow and it moves into this trade finance use case.”

This phenomenon has also ultimately seen the technology moving into sectors completely unconnected to early adopter industries, which has created particular opportunities for providers.

“Some large fast-moving consumer goods companies are hearing from their distributors in Africa: ‘We’re struggling to access US dollars to pay you, but we can easily access stablecoins – can we use those instead?’,” says Triple-A’s Barbier. “Naturally, these major companies aren’t comfortable handling crypto directly, and that’s where Triple-A comes in.”

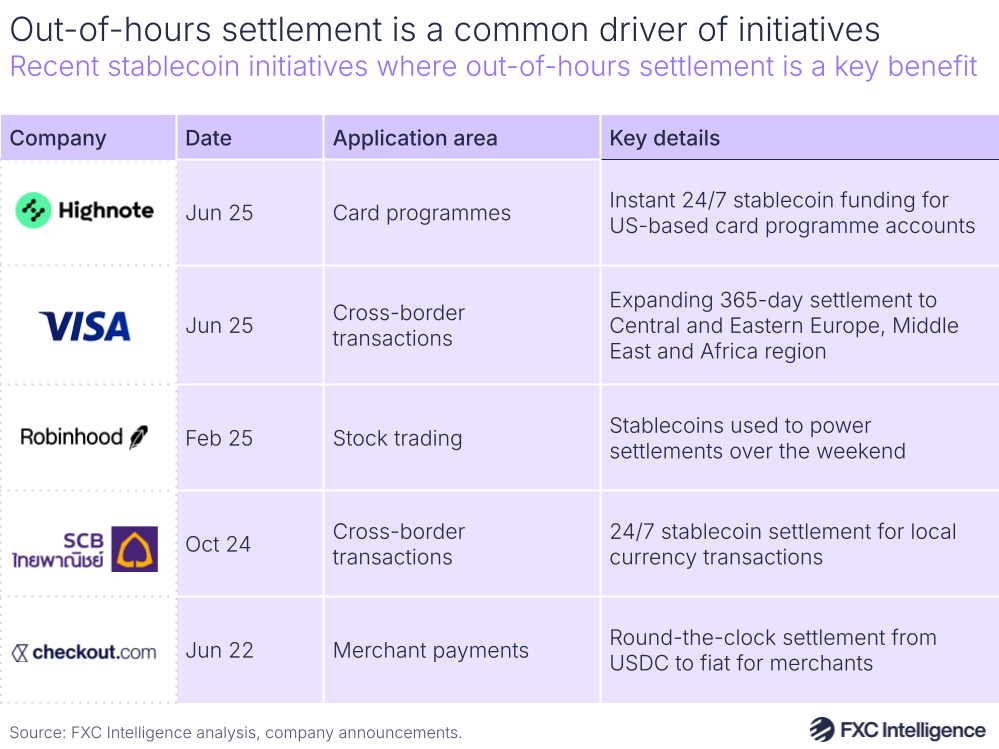

Out-of-hours settlement

While speed may not be an issue in many parts of the world during banking hours, when it comes to the weekend, even developed markets can face challenges, particularly when it comes to settlements.

“For some businesses, being able to settle 24/7 during weekends and holidays makes a change,” says Triple-A’s Barbier.

“Because everything is pre-funded with your partner, being able to send money real time during weekends and bank holidays can really improve a working capital position.”

This has been a key driver of MoneyGram’s decision to use stablecoins for its own treasury function, with Tuttle saying that in certain markets and scenarios, “one may be able to trade in and out with certain currencies more quickly with stablecoin”.

“We do a lot of money movement where we have to predict the amount of currencies we need in a particular market for a particular period of time,” he says.

“That might be over weekends where the banking routes aren’t open, so stablecoins can enable us to work on a 24/7 basis, settle more often and trade in and out of currencies more often.”

This is also a benefit for other aspects of the payments industry, including card programmes such as those of card issuer Highnote, who recently adopted a stablecoin solution specifically to tackle out-of-hours settlement.

“Pre-fund is a massive issue in global payment systems, whether that’s card networks or those programs like Highnote that need to post collateral for four days of pre-fund for the weekend with the networks,” says BVNK’s Harmse.

“The ultimate goal is moving the card settlement flow on-chain, whether that starts from an issuer, a processor, to Visa, to a merchant acquirer, to the merchant. Then you’re using technology to solve the pre-fund problem, versus forcing people to hold pre-fund in these accounts as a risk mitigation.”

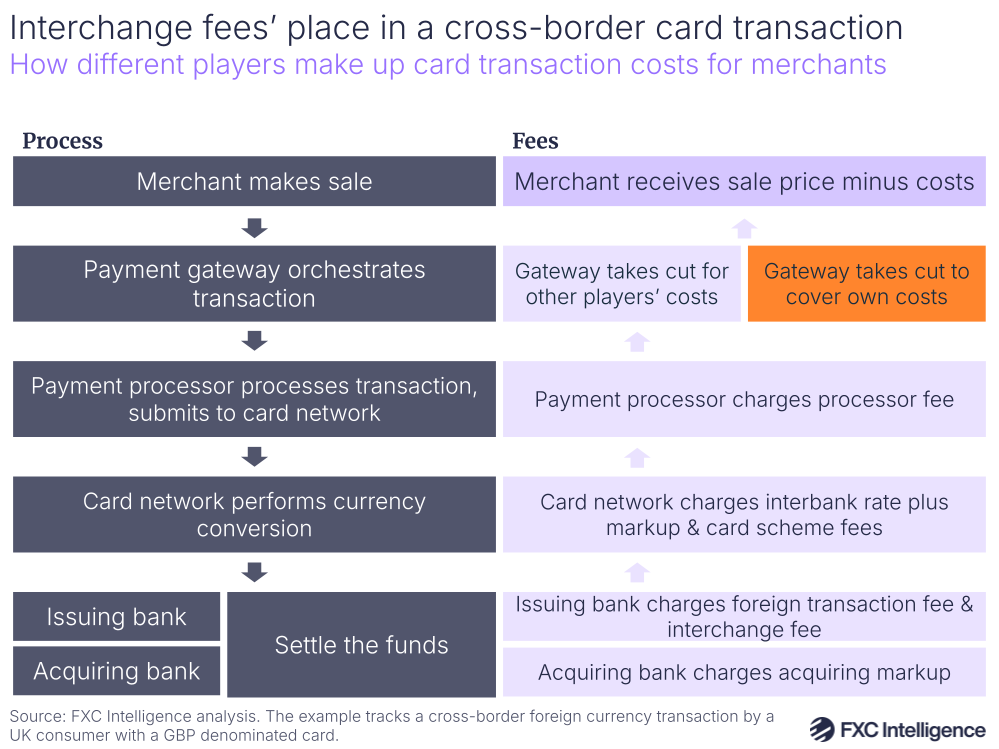

Interchange fee alternative

Meanwhile, one area that is emerging as a potential application in certain markets is the use of stablecoins instead of cards, particularly where the associated costs of such payments are high, such as in the US, where interchange fees are a particular concern.

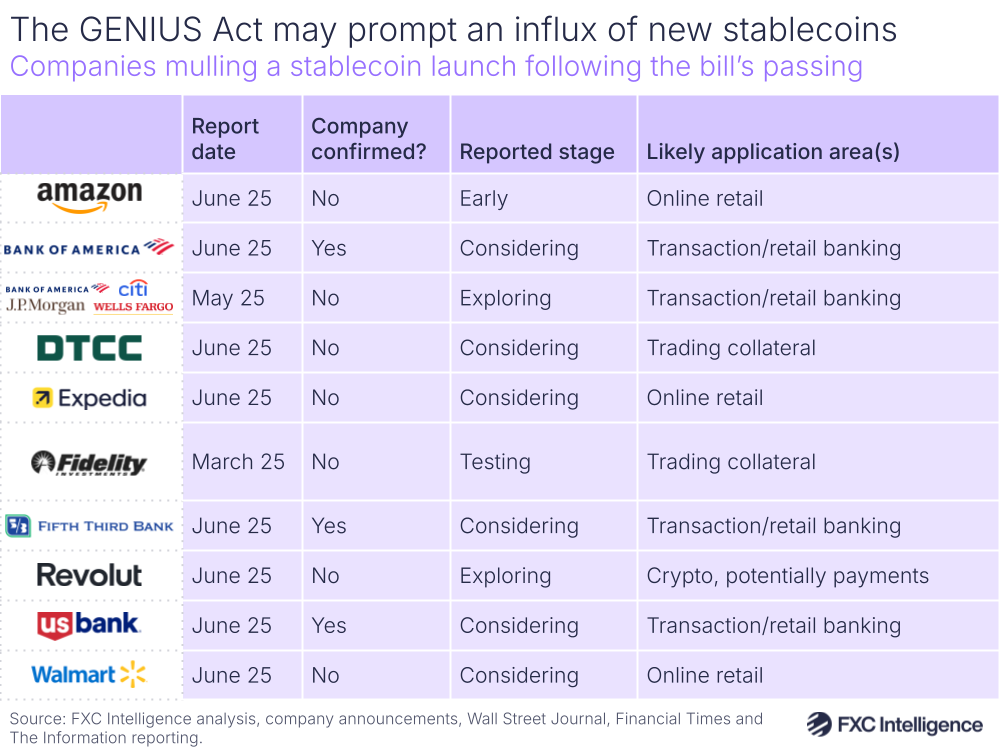

This is thought to be a key factor for some US companies reportedly considering launching their own stablecoins following the passage of the GENIUS Act. Amazon in particular is believed to be exploring its own stablecoin, which customers could hold and use to fund online purchases, allowing the company to avoid interchange fees on such transactions.

In this sense, stablecoins would effectively be a replacement for cards, however, not everyone is convinced.

“I still have a hard time understanding why consumers want to hold stablecoin,” says Airwallex’s Zhang.

“I’m getting a lot of rewards from my AmEx, I just have Apple Pay, I tap everywhere. Is Apple going to support stablecoin? Are all the merchant acquiring players all of a sudden going to accept stablecoin?

“I think we’re talking about a five to 10-year trend that may or may not happen.”

However, Higlobe’s Farman-Farmaian believes otherwise, arguing that his company is already seeing evidence of this. He reports that the lower cost of using QR payments versus cards is prompting merchants to incentivise payments by offering free extras, such as an additional drink or food item.

“We believe that stablecoins will erode the use of cards,” he says. “It’s what we see on the edges of in-person, no refund, no exchange retail.”

Stablecoin payments acceptance

If stablecoins are going to take share from cards, companies need to be able to accept payments using them, and this is an area that certain companies have built a business in, in part due to the ability to simplify the process for merchants who don’t want to engage with stablecoins or other crypto directly.

For example, according to Barbier, Triple-A began by “enabling merchants to sell to the 500 million people that have stablecoins or digital currency, while still being settled in dollars or euros on their bank account”.

“Our merchants come to us because at no point in time are they holding digital currency on their balance sheet,” he says.

BVNK, meanwhile, has had a stablecoin acceptance product for “the last couple of years” but while it previously remained relatively niche in terms of verticals, the company has recently seen it “starting to accelerate”, according to Harmse.

“The acceptance side is a sleeping giant. It was a use case that wasn’t in the mainstream and you really needed to get into ecommerce to really get to scale,” he says, adding that the recent growth in this area has in part been due to increased prevalence of stablecoins in key markets.

“We’ve seen use cases like pay-outs start to feed pay-ins because of acceptance, because once that Argentinian user has a stablecoin, they want to spend it somewhere.”

This growth has also been supported by a number of key recent developments, including Shopify adding merchant acceptance in stablecoins, aided by a general shift in attitudes towards the technology.

“The reputation risk of being associated with stablecoins and crypto is going away, so it’s getting easier to convince merchants, and in parallel the adoption on the ground has been really growing,” says Triple-A’s Barbier.

“They’re getting more and more demand to be able to accept stablecoin payments.”

While he reports that a significant minority of such transactions come from customers in developed markets due to their high spending power, the majority are from customers in emerging markets, who often struggle to make payments internationally using traditional payment instruments.

“There’s no risk of fraud, there’s no risk of chargeback, so compared to credit cards, especially in a cross-border environment, and especially when selling into emerging markets, it’s safer to accept,” he says, giving the example of luxury ecommerce platform Farfetch, which Triple-A is providing stablecoin acceptance services to.

“Because it’s luxury, it’s perceived as fairly high risk by the card schemes, and if you’re trying to pay, say from Kenya, that’s going to be a high-risk country so it’s very likely that the payment gateway in the middle is going to decline the card to avoid the risk of chargebacks. This means that for this guy in Kenya, his only option now is to use stablecoins to pay for those international merchants, and that’s the problem we’re solving.”

However, as with many other areas of stablecoins, this is not a use case that is yet seeing demand everywhere, and some remain skeptical about how much it can develop.

“I haven’t seen mainstream adoption and people wanting to hold in stablecoins yet, unless they can spend the money, and right now, only Visa and Mastercard have the network effect that allows them to be issuing a stablecoin-backed card to spend,” says Airwallex’s Zhang.

“I haven’t really seen like a wider spread of, you can spend everywhere. Maybe there’s a lot of closed-loop use cases, but the closed-loop channel has been around for like 20 years.”

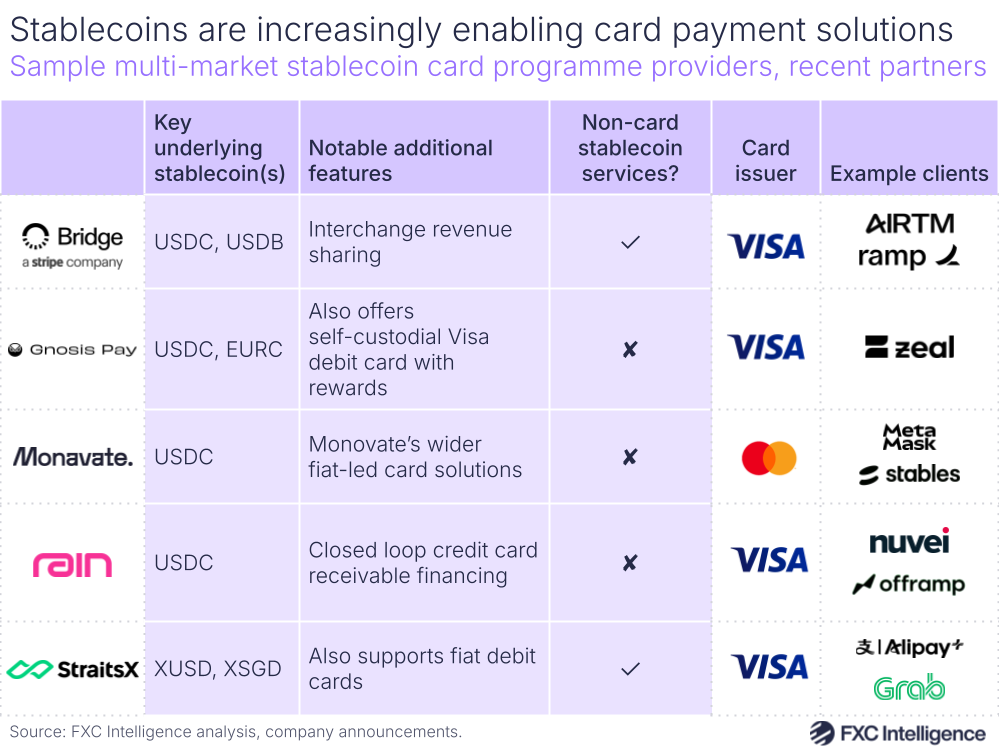

Stablecoin cards

Finally, while stablecoins are being framed as a replacement for cards, many stablecoin wallets come with their own virtual or physical cards, which typically enable balances to be spent online and at point-of-sale in retail settings.

This has created a growing market for multi-market card programmes, with Bridge, Rain and StraitsX among those providing solutions that form a central part of some customer-facing brands’ product offerings.

The current clients of such programmes vary. Many are providers of services that centre around stablecoins, typically in the form of consumer or business-focused accounts, often attached to pay-in and pay-out capabilities. However there are also growing numbers of fiat-led brands looking to add stablecoin capabilities, and card programmes are providing a familiar means for users to access and engage with these.

How do stablecoins compete on price?

When it comes to price, there are those that claim stablecoins are inherently cheaper than incumbent cross-border payments systems; however, the reality is more complex. There is evidence to suggest that at present stablecoins are cheaper for some markets. However, with current players operating on a far more limited scale, and in some cases subsiding their offerings as they build their customer base, it’s not clear if that will hold out across all areas as the market develops – or if scale will bring further cost efficiencies.

For some in the space, such as consumer-focused Sling Money, the goal is to keep prioritising price reductions.

“We want to get the price of sending money as close to zero as possible and make it as simple as possible,” says Sling Money’s Hudack.

“I should be able to send money to you, whether you’re sitting next to me or 3,000 miles away, with just a couple taps and it should be free or almost free. Stablecoins make that possible: they’re a really fundamental technological shift.”

However, this goal is similar to that of fiat-based Wise, a money transfers provider and global payments platform, and CFO Emmanuel Thomassin rejects the idea that stablecoins can undercut the money transfer player in its key markets.

“The reality right now is that the cost of moving money using stablecoins is actually still higher than just using Wise on most routes,” says Wise’s Thomassin.

“There might be some exceptions to this for certain currency routes that are traditionally seen by financial institutions as ‘higher risk’. Similarly, there may potentially be benefits for the technology in markets facing hyperinflation and experiencing regular currency devaluation.”

Meanwhile, others see the current reality as a mix: not cheaper in every corridor, but providing benefits in some.

“I can’t make as bold of a statement as saying all the corridors all the time,” says OpenPayd’s Dimitrova. “But for those corridors that we have seen benefits, the majority of time, there are definitely efficiencies.”

Our own research supports this variation. We analysed the cost of bank-to-bank consumer money transfers for a sample of three stablecoin-based providers on key corridors, comparing this against our FX pricing data for the same service from non-stablecoin players.

We found that while there was often a stablecoin offering cheaper than the non-stablecoin average, not every corridor saw the stablecoin offering averaging cheaper than the non-stablecoin average. Of these, only a small number saw the stablecoin average sitting below the average of the cheapest non-stablecoin players. However, in general, emerging market corridors were more likely the markets where stablecoins competed.

This is also reflected in what white-label providers are seeing.

“Costs have gotten a lot better as volumes moved on-chain. In the exotic markets, those are still very painful for many people and very expensive, so it’s on par with if not better in some of those markets,” says BVNK’s Harmse.

“It is almost as competitive as some of the really, really big liquid FX markets like Eurodollar – it’s not there yet, but it’s near.”

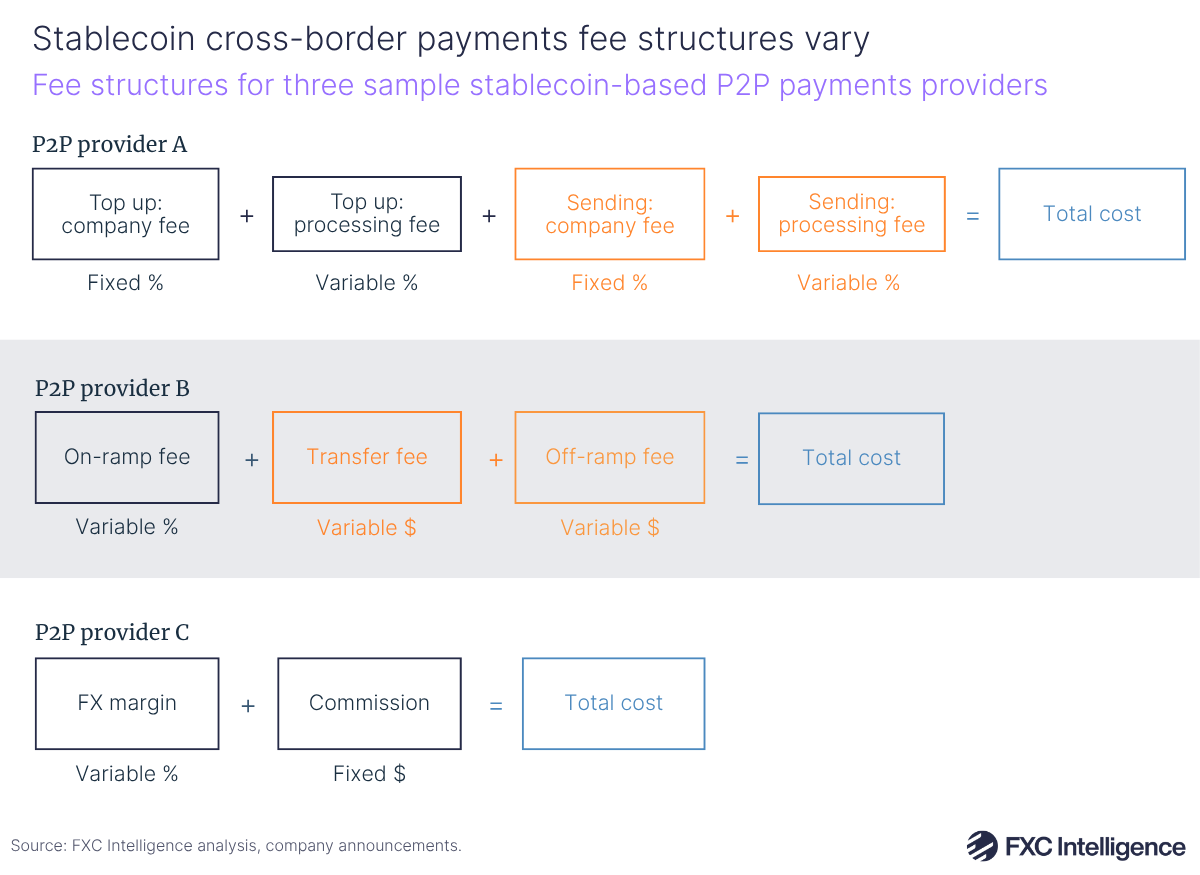

The makeup of stablecoin costs

Analysis of the way consumer money transfer providers using stablecoins report their fee structures to customers shows a wide variation in approaches. While some take an approach very similar to fiat-based providers, with a pricing structure similar to a combined FX margin and fee margin, others break their pricing down in a manner that aligns far more closely with the different cost components of delivering a stablecoin-based payment across borders.

In simple terms, a stablecoin transaction’s costs come in three parts: the cost to on-ramp the money from the sending currency to stablecoin, the cost to send that stablecoin across the blockchain network, and the cost to off-ramp it on the receiving side in the local currency of the recipient.

The cost to move money across the network is exceptionally low if using the right blockchain, which is the source behind many claims of stablecoins’ far cheaper pricing. However, the on-ramping and off-ramping is where the vast majority of costs come in, and has in the past been a significant foil to claims of very low costs.

“Last mile delivery needs to be fast or instant, ideally, and it needs to be extremely cost-efficient. But up until fairly recently, it was actually super inefficient,” says Conduit’s Gertman, explaining that this was because companies typically had to use an exchange for this process.

“They were the only ones who were able to essentially off-ramp into local currency.”

Our prior analysis has found that this typically saw costs that brought margins in line with or above those of traditional players, making such exchanges a key barrier to cost reductions from stablecoin-based payments. However, many companies have increasingly developed local partnerships that allow them to manage the on and off-ramp process more efficiently – and at a much lower cost.

“We’ve started working directly with local banks, meaning they have a lot more liquidity,” says Gertman, giving the example of a partnership Conduit has with Brazilian bank Braza that sees payments initiated in the local currency, BRL, and instantly minted into a stablecoin pegged to it, BBRL.

“We then are able to exchange that for a European stablecoin, on-chain, which means it’s almost instant and not quite free, but almost free. We then burn it, so take the underlying euro of that stablecoin and send it to the recipient. That whole process for us takes 120 seconds, so two minutes end-to-end.”

The instant settlement also removes the need to maintain liquidity pools, with many seeing efficiencies such as these as being key to achieving stablecoins’ lower pricing.

“We have a belief that we can do this with fewer moving parts than a traditional money movement product. We don’t have to maintain a central ledger of everybody’s money: the ledger is the blockchain; our client software talks directly to the blockchain,” says Sling Money’s Hudack, although he acknowledges that the company’s fiat costs for end transactions such as those on ACH or RTP are “the same as everybody else”.

“There are a lot of efficiencies inherent in treating money as a first-class digital good that you get as a result.”

However, if this approach holds true, particularly on the price-focused consumer payments side of the industry, it will create a “race to the bottom”, according to Farman-Farmaian, whose company Higlobe’s mission is to “move the world’s money instantly and at no cost”. This raises the question of how it can make money, however he sees there being a pivot towards a service model, where businesses can make the majority of their revenue on other products such as loans.

“This industry is going to look like Amazon. This industry is going to go to a model where instant money movement is going to be the table stakes,” he says. “Then there’s going to be fees and services provided in another way.”

The rise of stablecoin-based payment networks

While there are those whose entire business strategy is to deliver cross-border payments services to the end-user via stablecoins, whether that user is a business or an individual, there are also many more providing white-label stablecoin network services to other businesses.

For many existing businesses across cross-border payments, shifting wholly to stablecoins makes little sense for their business, but incorporating a solution as part of their wider network, which is used some or all of the time to deliver payments on certain corridors, is an appealing option, and is likely to be the dominant manner by which stablecoins infiltrate the cross-border payments space.

In this sense, customers and clients of such businesses may well be unaware of, and indeed uninterested in, whether stablecoins are used in the delivery of their payment, while it will not always be clear who in the industry is already using stablecoins, and on what corridors. At present, it is likely that more players are using the technology than have shared it publicly – and more still are exploring the possibility – but we cannot say for sure what share of the industry this currently applies to.

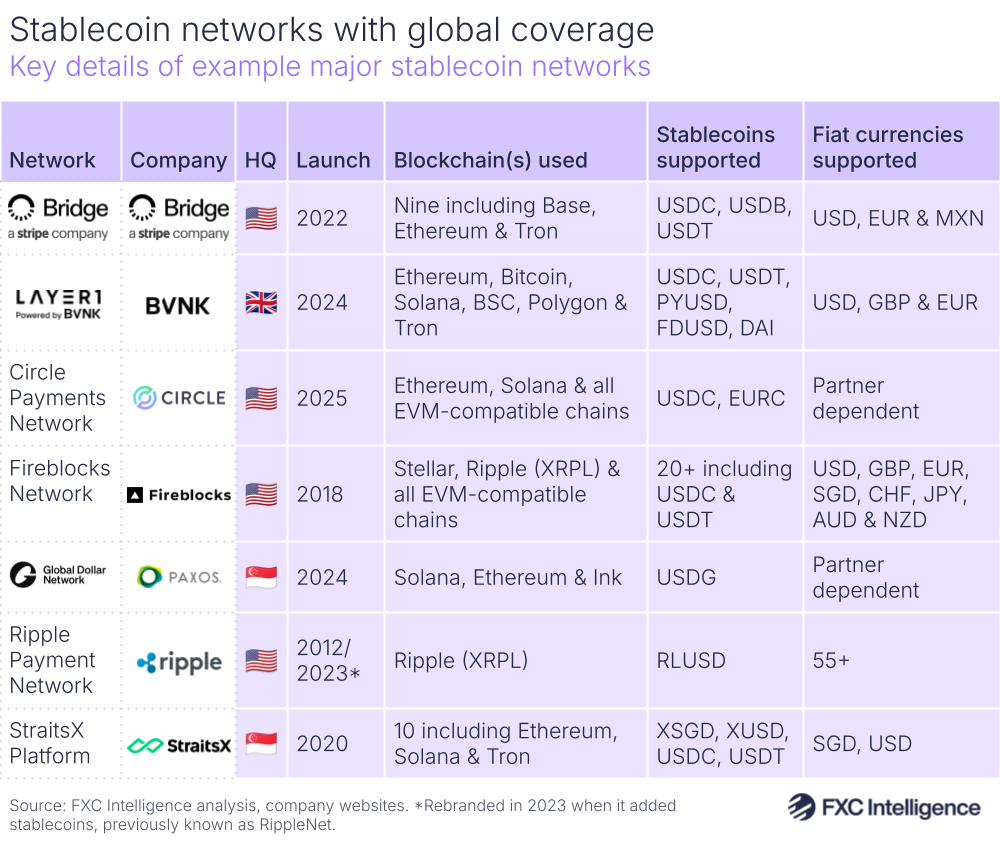

However, the rise of solutions for this market is clear evidence that it is growing. While B2B2X-focused stablecoin players such as BVNK, Fireblocks and StraitsX have been around for some time, recently we have seen the emergence of more formal network solutions that formalise these into plug-and-play-type additions for companies.

Last year for example, BVNK launched Layer1, a self-hosted, self-custody digital asset payments infrastructure that automates key aspects of the process.

“A lot of fintechs are leaning into stablecoins with solutions like Layer1 to be able to build on top of stablecoins, for different payment use cases,” says Harmse.

“We’ve seen it unlock a new type of customer, an enterprise PSP who is starting with us on the regulated side, but full well knows they’re going to probably get their own licence and then they just want to be able to build on top of a very powerful, hyper-optimised stack for global stablecoin payments. That’s quite exciting.”

Meanwhile, we have recently seen the launch of a number of other stablecoin-focused networks from players more traditionally associated with stablecoin issuing, in particular Circle’s Circle Payments Network (CPN) and Paxos’ Global Dollar Network.

Developed with support from Deutsche Bank, Santander, Societe Generale and Standard Chartered, CPN is a network based on USDC and Circle’s smaller euro-pegged stablecoin EURC. Acting as a marketplace for financial institutions, CPN has a defined ruleset and protocol set by Circle, enabling different players to interconnect and serve as each other’s local rails, without having to conduct individualised risk assessments for each partner.

“We are essentially building a technology layer that allows two parties to interact with each other using stablecoins without having to have known each other before,” explains Circle’s Chandhok.

“Even though they are relying on their own risk frameworks, we are presenting to them the CPN underwriting framework and saying party A and party B have gone through our underwriting process and we believe that they’re reliable.”

The network, which sees Circle take a basis-point fee for each transaction, is in particular designed to help those interested in the technology but unsure about the risk and technical processes to access the market, both as senders but also as an additional source of revenue as receivers.

“We have had banks come in who want to be senders, who want to be receivers. We have had PSPs come in who want to be senders, be receivers,” he adds.

“A lot of what can be done is unfolding in front of us. All the money transfer companies that are currently participating in cross-border payments are welcome to join CPN.”

So far, Circle has attracted a significant number of players to the network from across the industry. On the stablecoin side, this includes crypto-led organisations, as well as sector and region-specific players such as Africa-focused Yellow Card, as well as BVNK, Conduit, Triple-A and Fireblocks. Meanwhile, there are also a wide range of fiat-led companies that have signed up, including Nuvei, Zepz, Onafriq, dLocal and OpenPayd.

“Given our expertise in payments and the existing volumes that we already have within our network, for us being part of that network and that layer of orchestration where we remain in the flow and are the ones that effectively execute the first or last mile is frankly a no-brainer,” says OpenPayd’s Dimitrova.

“From Circle’s perspective, diving into our network of customers and into that fiat flow is very, very appealing.”

Meanwhile Paxos’s Singapore-led network Global Dollar Network takes a slightly different approach. With a significant roster of partners that include Nuvei, Orbital, Sling Money and Worldpay, it runs on USDG, a stablecoin with regulatory oversight both from the Monetary Authority of Singapore and Europe’s Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) rules.

This economic structure is arguably the biggest differentiating factor for Global Dollar Network. While Tether and Circle typically retain the interest income they make on reserves for their USDT and USDC stablecoins – although there can be some exceptions to this – USDG is designed to share revenue with network participants.

“You get rewarded based on your custody, your acceptance and your minting of USDG,” says Kendall.

“Every token is tagged with the original minter, so as long as that token stays in circulation – it doesn’t have to go on your platform, it just has to be out there – you receive the revenue that it is generated from our underlying reserves.”

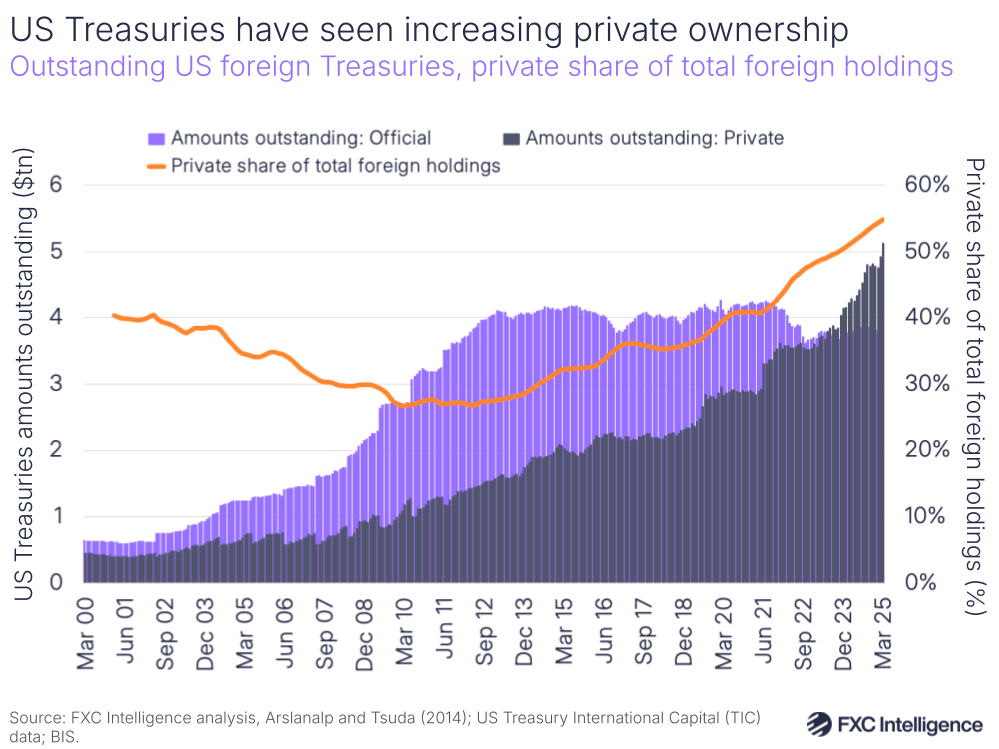

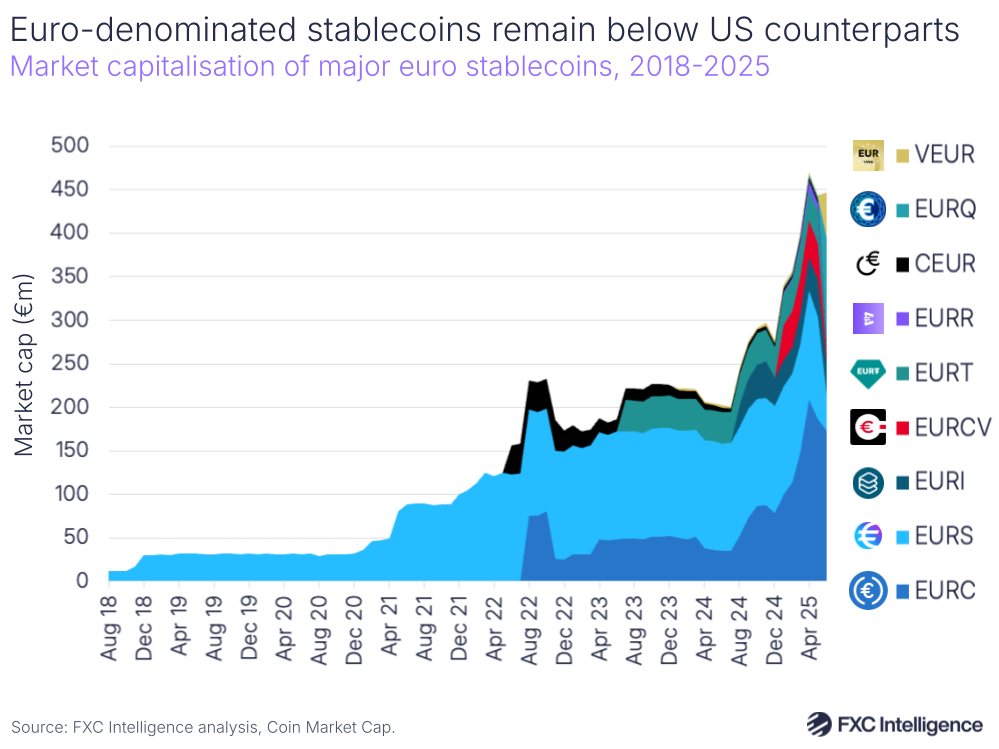

This model has been very appealing for some in the industry, with Higlobe’s Farman-Farmaian saying that Circle and Tether’s lack of yield sharing has caused anger from some quarters.