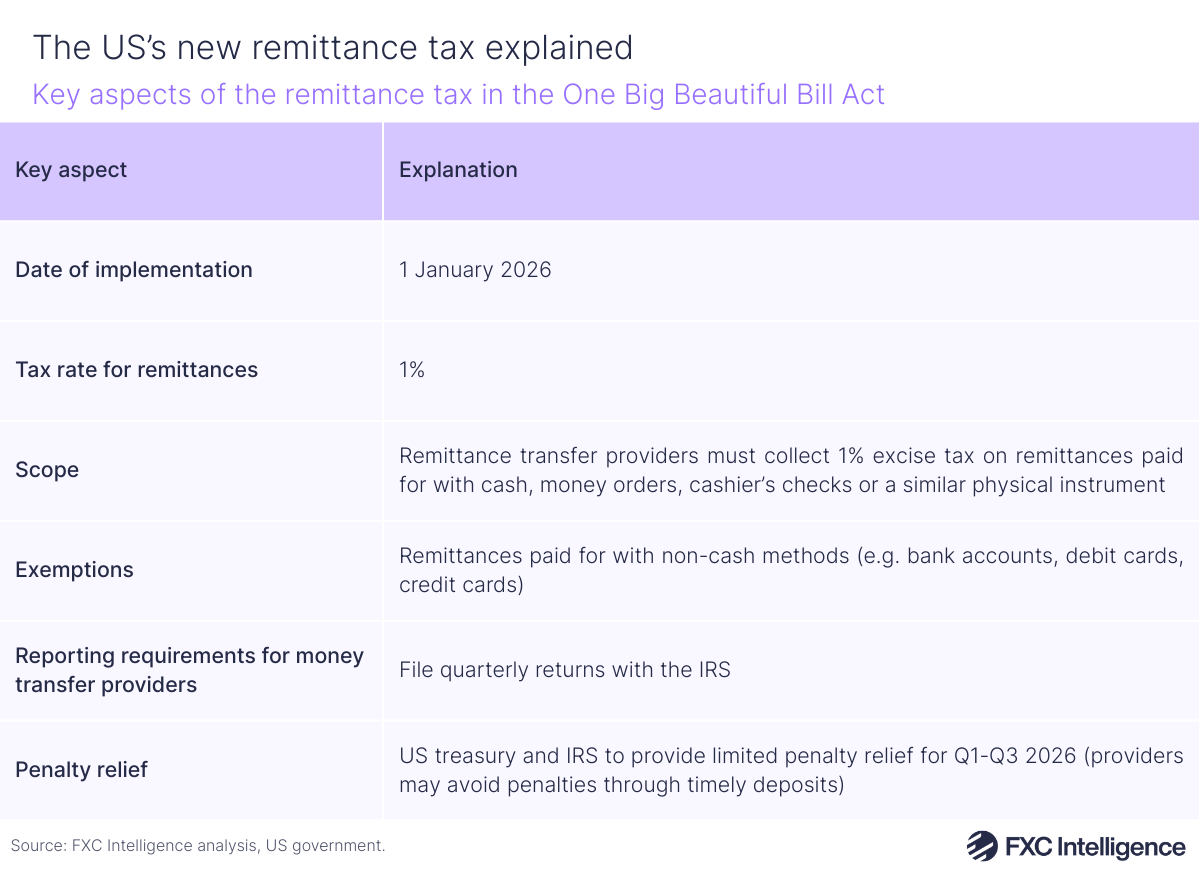

Starting on 1 January, the US introduced an additional 1% tax that applies to certain international money transfers – specifically to cash, money orders and cashier’s checks – as part of its One Big Beautiful Bill Act signed into law by President Trump in July 2025. We’ve looked at what this means for the industry, and how key money transfer providers are communicating the change to their customers in a variety of different ways.

Under the new tax, customers paying for money transfers in cash at a retail outlet need to pay an additional tax amounting to 1% of the transfer amount, separate to additional margins/fees being added by the money transfer provider. For example, a customer paying for a $1,000 transfer using physical currency has to pay the transfer provider an extra $10 in tax on top of the margin at the point of transacting. However, if customers use a different method to pay for transfers, such as through debit or credit cards, digital wallets or prepaid cards, they will not be subject to the tax. Receivers will not be affected, and the amount they receive will be the same.

Remittance providers that collect cash for transfers will face additional burdens. In particular, they must collect the tax and make semi-monthly deposits, while also filing quarterly returns with the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Failure to pay deposits means that providers could face penalties, though the IRS said in October that it will offer penalty relief for Q1-Q3 2026 as long as they satisfy certain conditions. The crux is that providers will need to have systems in place to adequately record data on transfers to show which are subject to the tax.

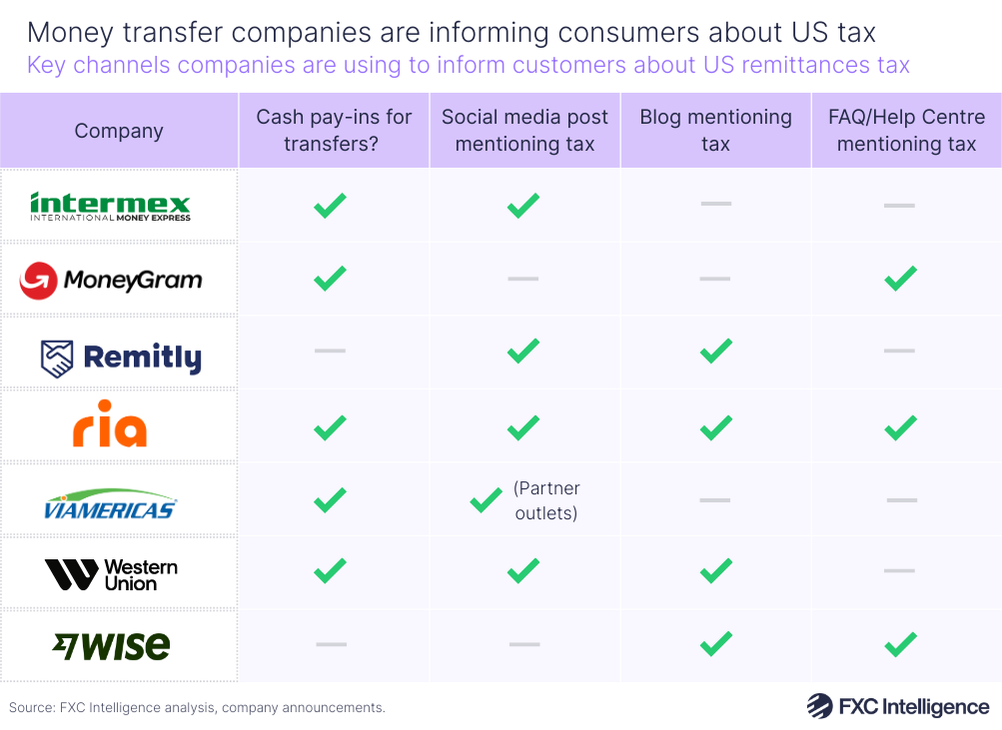

Because the remittance tax applies to cash, it is more relevant for those money transfer providers that support cash transfers and have retail locations where people pay for transfers in-store. This includes Western Union (as well as its recently acquired subsidiary Intermex), Ria and MoneyGram – all of which are focusing more on digital but still have large global networks of retail locations serving consumers sending money with cash.

Companies in the money transfer space have been active in telling their customers about the tax in a number of different ways, including blogs and Help Centre guides explaining the tax and how it works, questions about the tax in FAQ sections and social media posts. The way companies are communicating to customers about the tax could continue to evolve now that it is in force.

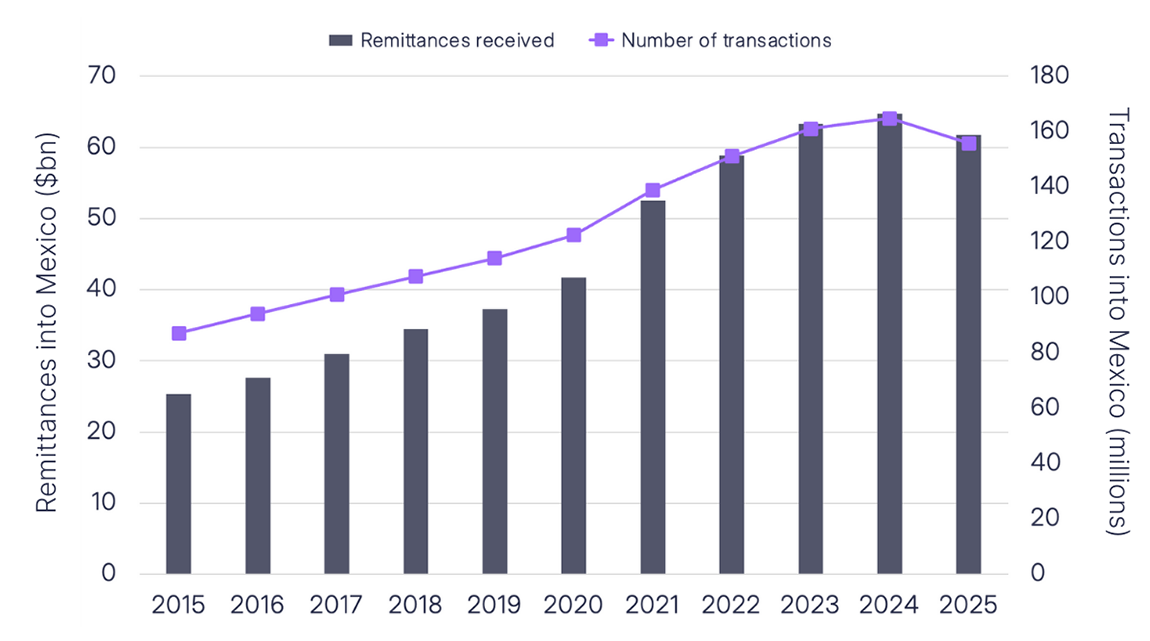

Aside from additional burdens for compliance and reporting, the move could see a shift in demand from consumers. The targeting of cash transfers could be particularly disruptive for undocumented migrants, many of whom are paid cash in hand and therefore remit in cash, as well as US citizens such as minority groups and the elderly. While some may be able to move to digital methods, such as paying for transfers online through debit cards or prepaid cards, others may send less money overseas to compensate for the tax and some could switch to using informal, non-regulated methods such as hawala, which uses brokers to move money across borders.

The wider impact of the tax remains to be seen, and we’ll continue to track how money transfer companies report changes in consumer behaviour this year.