The US’s ‘One Big Beautiful Bill Act’ includes a planned 3.5% tax to remittances from non-US citizens. In this report, we explore the potential implications of this new bill for the money transfers industry.

Last week, the House Republicans’ ‘One Big Beautiful Bill Act’ narrowly passed through the US House of Representatives with a 215-214 vote. The bill sets out US President Donald Trump’s tax agenda for the next few years, with sweeping cuts across various aspects of American society. However, for money transfer providers, the focus has largely been on a new 3.5% tax on remittances for non-US citizens.

Starting in 2026, the tax would amount to 3.5% of the send amount for transfers. It would be collected by remittance service providers, banks and money transfer apps and paid every quarter to the US treasury. With no minimum transaction limit, even smaller transfers will be taxed, meaning that this could pose a significant hike for non-citizens living in the US and potentially shift consumer behaviour in an unprecedented way.

Originally 5%, the proposed tax was reduced to 3.5% following a last-minute amendment before the vote. It comes as part of a wider scheme of measures from the US government targeting immigrants, with much of the resulting coverage speaking about the potential impact on the foreign-born population in the US.

As it is written, the tax is expected to affect nearly 50 million people, including green card holders and non-immigrant visa holders, such as those visiting for leisure or work, as well as unauthorised immigrants. While the close to 25 million naturalised citizens (i.e. born abroad but have since gained citizenship) in the US are exempt from the tax, any citizens who want to send remittances abroad through a “qualified” money transfer provider would need to provide proof of their citizenship to do so.

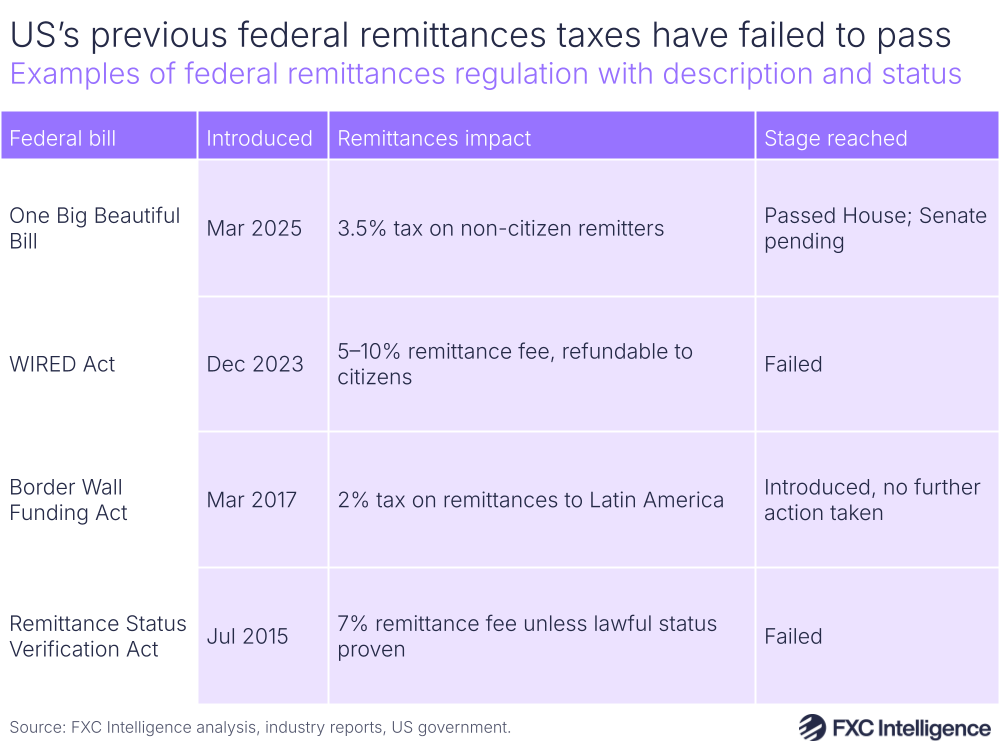

Various states in the US have introduced bills to tax remittances before, but the majority have failed to pass, with many not moving past the committee stage. Meanwhile, the proposed remittances tax has come as something of a surprise to the money transfers industry, with its far reach into the customer base of big players such as MoneyGram and Western Union, as well as the potential burdens it would create from a verification and KYC perspective.

In this report, we’ve taken a closer look at the implications of the proposed remittances tax for money transfer providers, as well as what could come next.

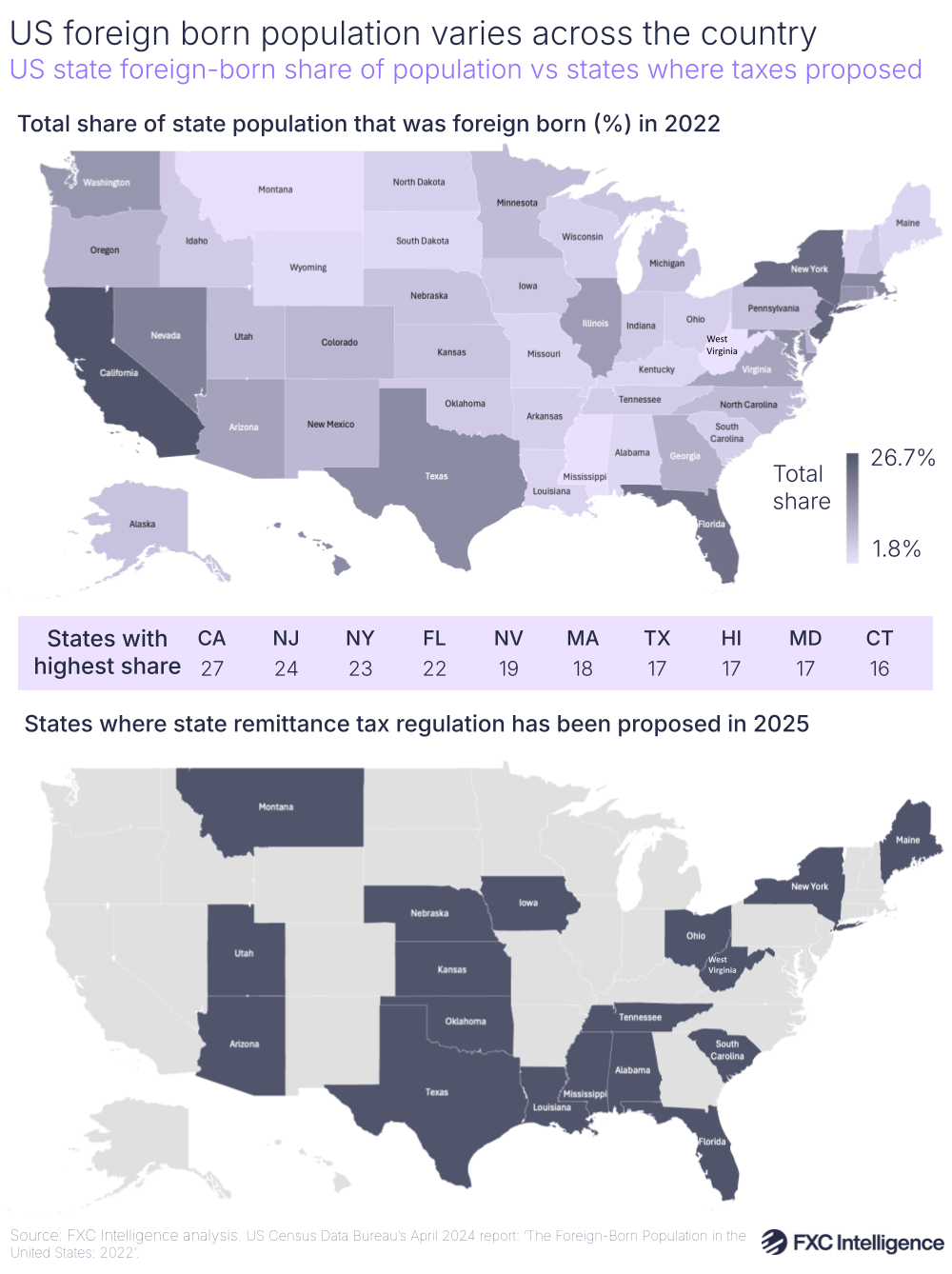

Assessing the foreign-born population in the US

Vast numbers of people send money home from the US, including naturalised citizens, legal migrants, visitors and unauthorised immigrants. As the number of foreign-born immigrants residing in the US has grown, so too has the country’s potential customer base for transfers.

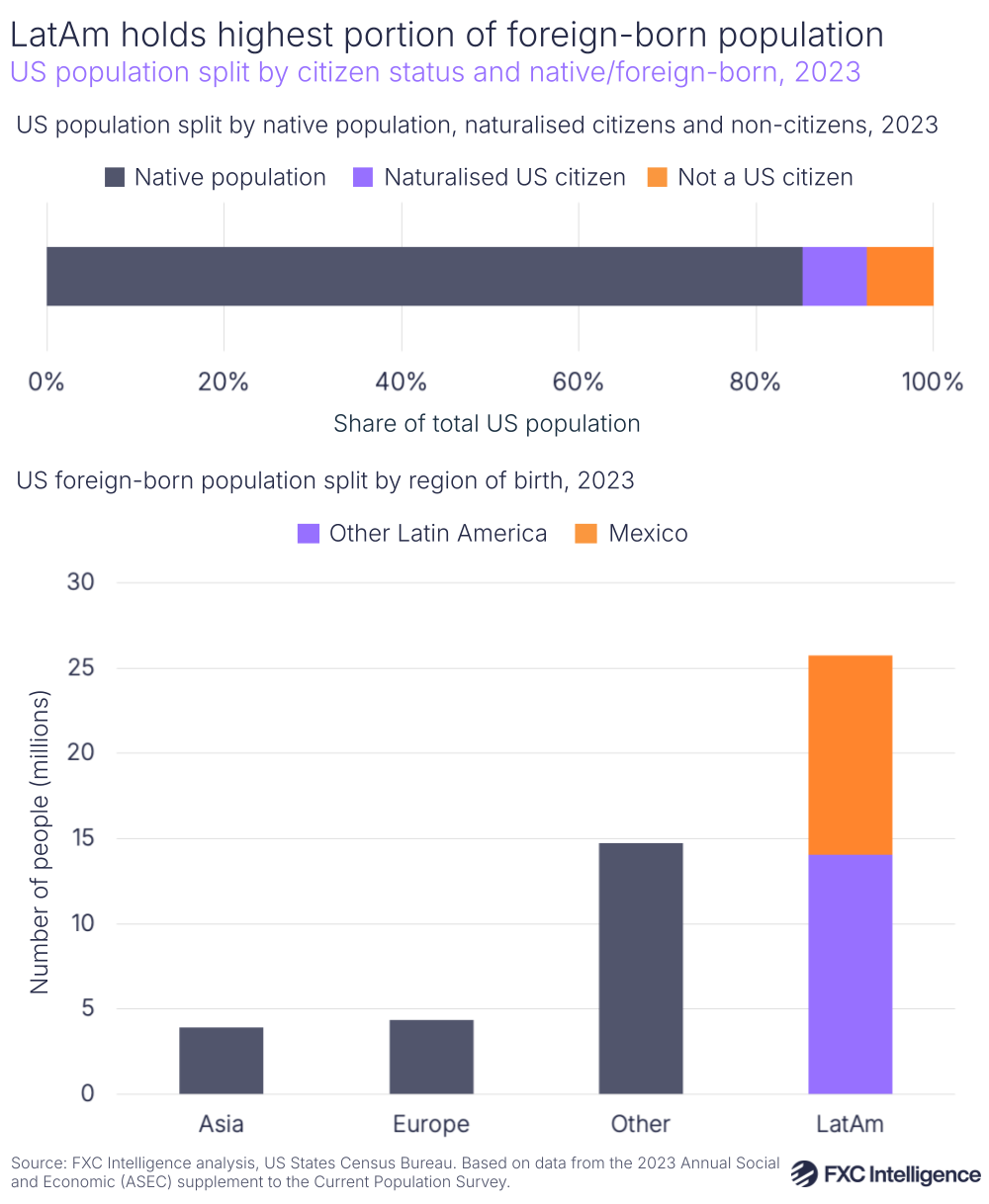

According to the 2023 Annual Social and Economic (ASEC) Supplement to Current Population Survey, 85% of the US population in 2023 were native-born, with 15% (around 48.8 million people) being foreign-born. Of the latter, 8% (nearly 25 million) were not classified as a US citizen while 7% (24 million) were naturalised.

Based on ASEC figures for 2023, LatAm was the region of birth for 53% of the US’s foreign-born population and 8% of the population overall. Of this group, Mexico was the place of birth for 24% of the foreign-born population overall and 4% of the total US population. Europe and Asia made up 9% and 8% respectively of the total foreign-born population.

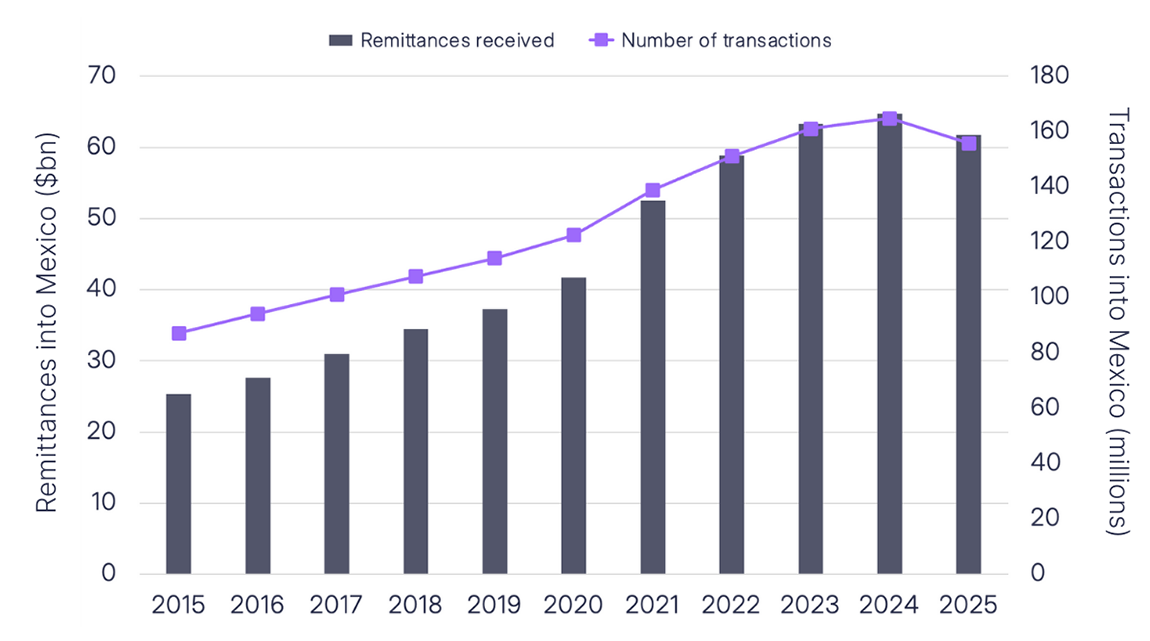

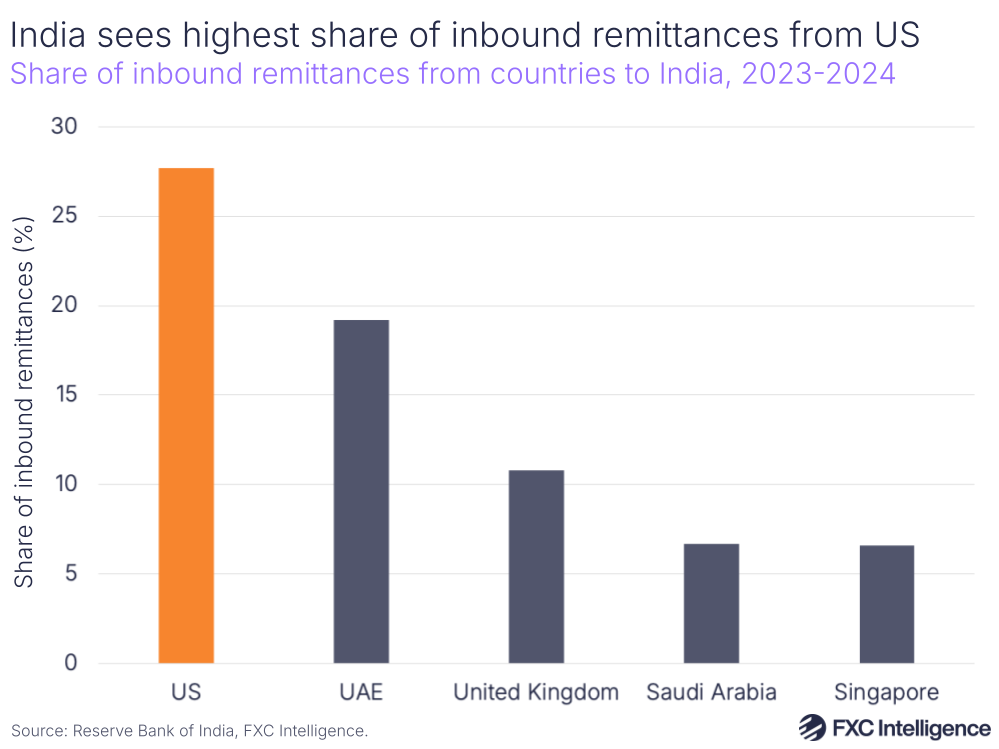

India and Mexico are two of the biggest recipients of remittances in the US, and have therefore seen a substantial media and political response to the newly proposed bills. For India, the top recipient of remittances in the world, the US provided 28% of the country’s inward remittances in the fiscal year ending in March 2024, according to data from the country’s central bank.

Meanwhile, remittances from abroad accounted for 3.7% of Mexico’s total GDP in 2023. Last week, Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum welcomed the US lowering its proposed remittances tax, but said her administration was speaking to both Republican and Democratic senators to explain why any form of tax would be harmful for the country.

Having said this, other countries in Latin America are even more reliant than Mexico on remittances and could be even harder hit by changes in transaction volumes. According to World Bank figures, in 2023 Honduras and Nicaragua both saw inbound remittances account for 26% of GDP, with El Salvador at 24% and Guatemala at 19%.

However, as further analysis shows below, the extent to which the bill will actually stop these flows – or if the bill will have an impact on illegal migration – is unclear.

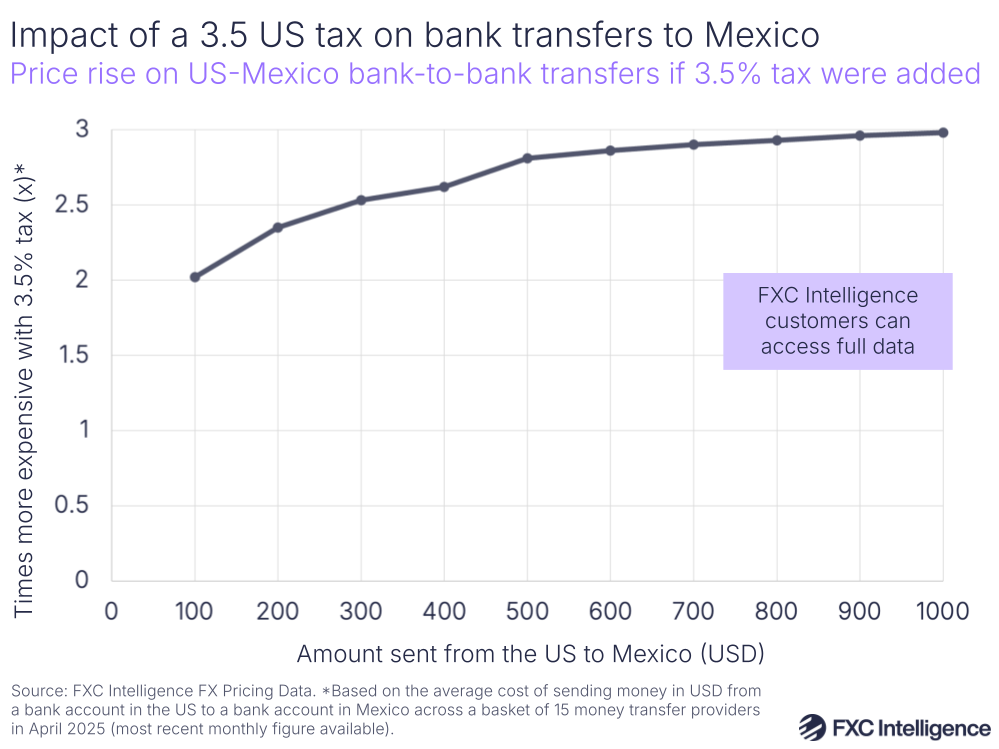

How the tax could drive up remittance pricing

To get a sense of the potential impact on pricing, we’ve taken the average cost of sending different US dollar amounts from the US to Mexico via bank-to-bank transfer, across 15 different providers in April 2024, using FXC Intelligence’s FX Pricing Data. We have identified the impact of adding a 3.5% tax margin to the price of the transfer for each send amount.

According to the bill, the 3.5% margin would be added to the amount of the transfer, meaning that it would be a cost levied on the send amount, in addition to the costs charged by the remittance provider. Based on the average cost across the providers we reviewed, it could cost up to twice as much to make an international transfer for a send of $100, rising to three times the cost for sending $1,000.

According to figures provided by the UN, on average migrant workers send between $200 and $300 home every one or two months, constituting around 15% of what they earn, with the rest staying in the country where they are working. However, what they do send can make up as much as 60% of a household’s total income.

Though this figure applies to global remittances, it puts in perspective that a person sending $200-300 from the US to Mexico through a money transfer provider would have to pay over twice as much to do so with the new taxes.

The UN’s sustainable development goal is targeting 3% or less global average cost for sending $200 in migrant remittances by 2030. As we discussed in our full breakdown of the industry’s progress towards G20 and UN goals last year, the FSB reported that the global average cost to send $200 was at 6.4% in 2024.

Much of the focus and coverage of the bill’s impact has been on the impact of foreign-born consumers in the US, as well as the countries they hail from. However, depending on verification that money transfer providers could require, it could also have an impact on US citizens trying to transfer money – for example if they don’t have the correct ID available. Such cases could serve to impact a number of customer profiles, such as military families sending money to service members abroad; families sending money to students overseas; and even transfers to recipients in other states.

How consumer behaviour could change

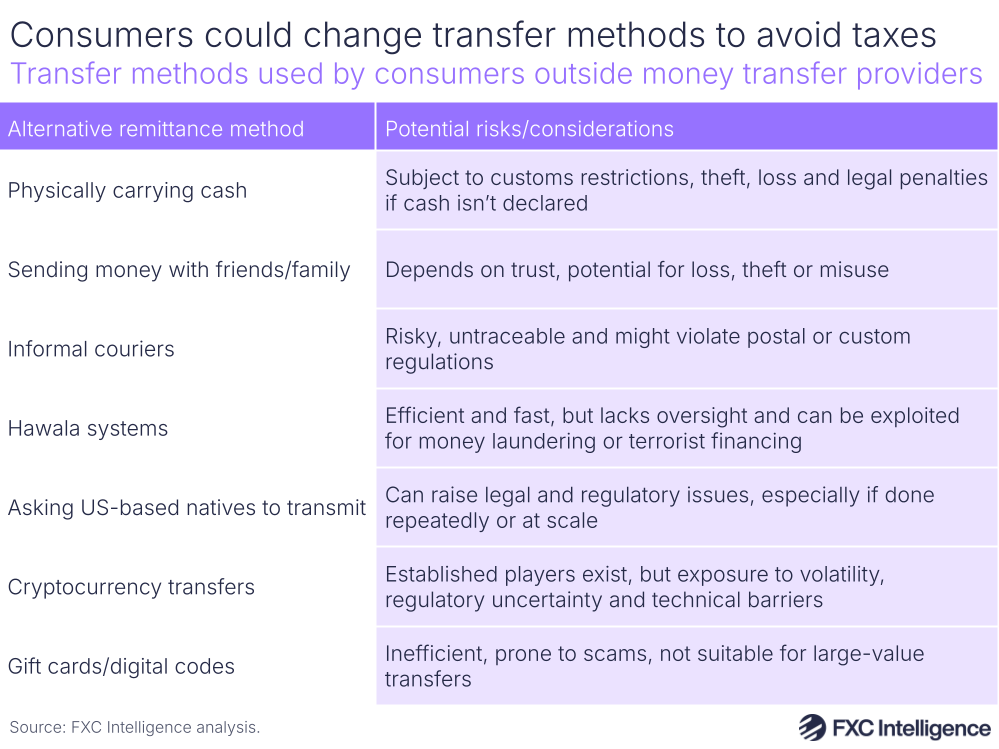

Given the sheer amount of outbound remittances from the US, it is unlikely that people will stop sending money from the US, but they might change the way they do it. Remittance taxes could encourage regular cross-border remittors to use informal mechanisms to avoid paying taxes, such as through mules or hawala networks (an informal method of transfers through unlicensed brokers). For licensed industry players, this could put a dent in their transactions, though bigger victims could be smaller businesses that partner with money transfer providers (e.g. a grocery store with a Western Union outlet), which could see less footfall due to losing services.

Currently money transfer providers have to comply with federal and state anti-money laundering laws. However, an influx of “underground” transactions outside these players could stop law enforcement agencies from being able to track how money is moving, and give financial backing to services that lead to the same issues that legislators could be trying to avoid – such as money laundering, financing bad actors and drug trafficking.

One aspect of the bill that has drawn particular attention is the extent to which it could spur a move to crypto remittances. As we found in our report on Latin America, crypto adoption has significantly risen in the region, in some cases due to economic instability, while a ChainAnalysis report found that Mexico is one of four of the top 20 countries in the world for crypto adoption. For those sending money back to Mexico from the US, for example, remittances through a digital-only currency could be a natural fit.

However, there is still uncertainty over the extent to which such remittances would be covered by the bill. The bill works with the same definition of ‘remittance transfer provider’ that was given in the Electronic Fund Transfer Act, in particular: “any person or financial institution that provides remittance transfers for a consumer in the normal course of its business, whether or not the consumer holds an account with such person or financial institution”.

According to Kathy Tomasofsky, Executive Director of the Money Services Business Association (MSBA), crypto payments would be covered by the wording of the bill, though there is some question as to whether they would be able to configure payments to be excluded. Having said this, other sources have reported that using self-custody crypto wallets would be possible to use as a remittance transfer, as they are not clearly identifiable as remittance transfer providers based on existing definitions in law.

Potential challenges for money transfer providers

Aside from the fact that consumers could remit less through licensed money transfer provider channels, Tomasofsky says that remittance taxes have a wide range of ramifications for money transfer players that legislators often don’t account for. This applies both to state bills that have fallen by the wayside in the past and in this new federal bill.

The MSBA argues that such taxes add expenses and burdens for companies without seeing a benefit, forcing them to either pass on those costs to consumers – against global efforts to bring costs down – or cut their services to existing states. Part of this is from the difficulty of installing systems for verifying and ensuring that customers are US citizens.

For customers that enter a Western Union branch and need to show their ID to make a money transfer, the journey doesn’t stop there for the transfer provider. Western Union would need to prove that it had verified the customer, which in turn would require it to keep that person’s information on record – i.e. by taking a photo of their passport and recording their documents. Implementing a system for this would create additional costs and could also open up additional data privacy and compliance requirements, as the companies would then be storing personal data on their platform.

Under the text of the bill, a 3.5% tax would be imposed on any sender through a remittance transfer service, with the exception of transfers sent by US citizens (who have full citizenship rights) and US nationals (born in US territories but not having full citizenship rights) through a “qualified” money transfer provider. The bill defines a qualified remittance provider as: “any remittance transfer provider which enters into a written agreement with the Secretary pursuant to which such provider agrees to verify the status of senders as citizens or nationals of the United States in such manner, and in accordance with such procedures, as the Secretary may specify”.

However, the bill is still ambiguous on whether it is optional to become a qualified provider, how to register as one and whether it will cost any money to do so. Licensed money transfer providers in the US already have to pay for licences and register with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) as part of know your customer obligations. Adding another process could cause them another burden.

“Right now, FinCEN registration doesn’t cost you any money, but your licence renewals do, and they could be sizeable based on volumes and different things,” says Tomasofsky. “Is that more money that the company is going to have to spend to register? It’s unclear.”

The question of whether it is optional to become qualified is relevant, as the wording of the bill suggests un-qualified transfer providers could simply collect the tax in order to avoid the difficulties around collecting user information. The bill stipulates that consumers that are taxed can file for a credit in their return to receive the money back, if they can provide certain information, such as their Social Security number.

Will the US benefit from the remittances tax?

There are a few reasons that are likely to be driving the inclusion of a tax within the wider US bill. One is a continued push to expand border security, which has been a discussion point for remittances legislation in the past, and for which the bill has allocated $46.5bn.

However, with so much still unknown about how the bill will operate in practice, it’s not certain whether the US will see sizeable benefits from the remittances tax. Before the proposed tax was reduced to 3.5%, the US Joint Committee on Taxation projected that it would raise just over $1bn in 2026, with this rising every year to accrue a total of $22bn by 2034.

Now that the proposed tax has been reduced to 3.5%, the amount raised is likely to be considerably lower, but it is also unclear which data was used to calculate these figures in the first place, and indeed the extent to which they have been adjusted to reflect a potential shift in the way consumers make remittances over time.

According to analysis from Dilip Ratha, Economic Adviser to the Vice President of Operations at the World Bank’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency, a 3.5% tax on outward remittances sent by unauthorised migrants is likely to raise less than $1bn in revenue.

Ratha estimates that a reduction in remittance volumes in response to a 3.5% tax would likely be $90m – a relatively small decrease, compared with $84.3bn in outward remittances sent in 2024. In terms of whether the bill would actually work to deter immigration and encourage immigrants to move home, Ratha is sceptical, saying a minimum wage job in the US provides a salary between four to 30 times more than in a developing country.

“A 3.5% tax is unlikely to discourage remittances,” he said in a note circulated in response to a request for comment from governments and money transfer providers. “After all, the main motivation for migration – migrants trying to cross oceans and rivers and mountains – is to send money home to help helpless family members.”

Tomasofksy, meanwhile, expresses that the sheer amount of money being sent abroad means that a remittances tax could end up exacerbating the issue of unauthorised migrants. “So much of the GDP in Latin America is because of the money that is sent out of this country,” she argues. “If that’s not there and you put people in a desperate mode, more will come to the border.

“If people are desperate for food, they will come forward. There’s no loss for them. If your family is starving and you may get killed going up there [from Latin American countries], what is the downside to you? They can’t comprehend the desperation that people can feel.”

State remittance taxes ramp up in 2025

The US has tried to tax remittances on both a federal and state level before, though has seen very little progress on this front. On a federal level, this includes the Remittance Status Verification Act in 2015; the Border Wall Funding Act of 2017; and the WIRED Act in 2023, which was co-sponsored by then Senator and now Vice-President of the United States JD Vance. However, these bills did not pass for various reasons, with some of these being technical difficulties to do with their implementation.

A number of state bills have been presented, though the vast majority of them did not get past the committee stage. One notable exception is Oklahoma, which in 2009 added a tax on money transfers of $5 plus 1% on amounts over $500, with proceeds going to the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs. Only customers with a valid social security number or valid taxpayer ID number could reclaim a tax credit. Additional legislation to try and boost this fee was introduced earlier this year.

A 2016 report from the US Government Accountability Office found that several providers had reported lower transactions and revenues as a result of the Oklahoma bill. Providers featured in the report also noted several negative potential impacts as a result of new proof-of-legal status around remittances, including higher costs from having to add new computer infrastructure and databases, staff training and compliance costs.

This year has seen a significant increase in the number of bills that have been introduced. According to Tomasofsky, in the past six months the US has seen 18 states and 28 bills put forward to try and tax remittances and add verification of US citizenship. However, with the exception of Louisiana and Ohio, which are ongoing, all of these bills have failed to pass.

Tomasofsky says that this year has seen added impetus on the back of US President Donald Trump’s re-election, which has seen a significant boost to anti-immigration bills and rhetoric in the country. With regards to remittances, it has amplified a feeling amongst some of the population that the money immigrants make in the US should stay and be taxed in the US – despite evidence that undocumented immigrants can (and do) file federal tax returns.

“There’s always exceptions, but the negative aspects of the rhetoric and the anti-immigration have been amplified, and that’s what’s causing so much chaos,” says Tomasofsky.

The reason why bills have failed is different in each state vary, but often the killing blow comes when the state committees considering them come to realise the actual impact of the legislation on business. Tomasofsky gives the example of Utah, which was one of the first states where such a bill was stopped, with support from lobbying efforts by the MSBA. Aside from being home to a number of technology companies such as SoFi-owned fintech Galileo, Utah also has a strong Mormon community that carries out outreach in other countries, and therefore often needs to send money to missionaries abroad.

Elsewhere, Iowa’s tax was designed to target human trafficking, but the MSBA argued that consumers going “underground” due to new laws would affect the visibility of transactions to law enforcement. Meanwhile, in Alabama, there was a strong argument that the amount of tax revenue raised through a proposed tax would not be as high as expected, and the state also has large construction and farming industries with high proportions of migrant workers. “They have a lot of illegal people, and guess what? People in the US don’t want those jobs,” Tomasofsky adds.

“What we try to do is decouple the remittance tax piece from the other immigration issues. By decoupling and focusing just on our ID and verification, they’re able to move forward with their anti-immigration rhetoric and make people happy, and we’re in the background, killing it any way we can.”

Next steps for the US tax bill

With the bill having passed the House of Representatives, the legislation now moves to the Senate, where Republicans currently have a 53-47 majority. The Senate is expected to take up the bill in the coming weeks, with a number of debates and potential amendments anticipated.

Due to rules in the US around budget reconciliation, only a simple majority (i.e. 51 votes) would be needed to pass the bill – meaning that if Republicans are unified, it could pass without the support of any Democrat senators.

However, the bill still faces a number of hurdles and is facing a tight deadline, with US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent saying at the start of May that lawmakers need to raise the US’s debt ceiling – the legal limit on the total amount of money the US federal government can borrow – by mid-July to prevent the federal government from defaulting on its financial obligations. Republican leaders therefore aim to get the bill through the senate and to the President to sign by 4 July.

Crucially, the bill is vast, with significant – and in some cases controversial – changes besides the remittances tax that could take up much of the Senate’s attention. For example, the bill seeks to finance tax cuts through adding new restrictions to Medicaid, the US’s healthcare programme enrolled in by nearly 80 million people across the US, and raising the state and local tax cap, overhauling legislation Trump himself introduced to limit tax deductions for higher taxpayers.

Though a concession has already been made, the presence of other big talking points in the bill could work in the favour of opponents to the remittances tax. If public scrutiny moves away from lower-profile components, the tax could become a negotiable concession that could be removed or amended to appease senators and garner votes.

For Tomasofsky, the hope is that the MSBA can make US legislators hear the various challenges that could face the US remittances industry as a result of the bill passing through – particularly with regards to how it affects privacy, the way that it could affect businesses more widely, and how consumers may resort to taking remittances underground as a result.

“There are so many other components in that bill that have a lot more significant value and debate that they’re going to be more focused on,” says Tomasofsky.

“They’re going to be more focused on state taxes, Medicaid and tuition. There’s all this other stuff that is very sensitive and volatile that they’ll be focused on, that I’m also hoping that we could just make all our points and get out of the way. That’s my goal, but we’ll see.”

Though it might only span a few lines of a 1,000-page document, the introduction of a remittances tax could significantly impact consumers and businesses, leading to additional costs and logistical burdens for money transfer providers. If consumers opt outside established money transfer providers, they could enter new unregulated territories for transfers that end up causing more trouble for lawmakers. Even if some predict the actual impact on transactions won’t be affected, if the bill passes there could be significant challenges for money transfer providers ahead.