We’re continuing our series on the technical world of stablecoin payments to mark the launch of our Buyer’s Guide: Stablecoin Payment Infrastructure (learn more about purchasing a subscription or read the executive summary). And this week it’s time to unpack the fees and costs that make up a stablecoin transaction.

Prior to this year’s stablecoin boom, the prevailing narrative from those in the crypto industry was that stablecoin-based cross-border payments were significantly cheaper than their traditional fiat counterparts – a claim the payments industry was, with good reason, highly sceptical about. The basis of this claim is on-chain fees – often known as network or gas fees – which are the charges incurred during a transaction on a blockchain.

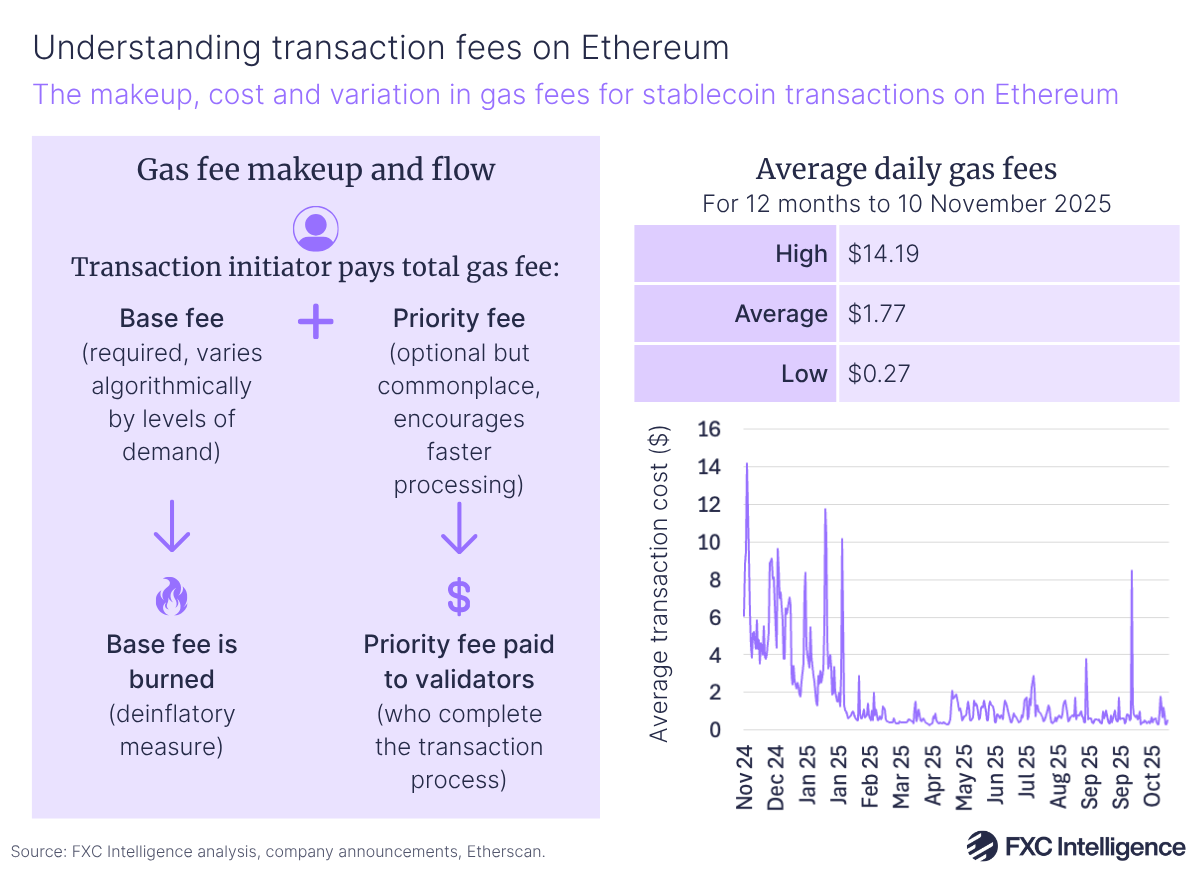

Gas fees vary in amount and makeup depending on the blockchain, but for leading blockchain Ethereum, which accounts for around 65% of USDC and 48% of USDT, they have two parts. The first is the base fee, which is set by the network, and the second is the priority fee, sometimes referred to as the tip, an optional additional fee that is in theory set by the person initiating the transaction, although in reality is typically determined by algorithms built into their wallets, trading software or bots.

Both increase in response to higher demands on the network, but in different ways: the base fee is varied algorithmically, while the priority fee is designed to move the transaction up the queue and get it processed faster. This variation can be significant, making the gas fee alone vary from tens of cents up to multiple dollars. However, these fees are not retained by the network itself. The base fee is burned (destroyed) as a disinflatory measure, while the priority fee is earned by the blockchain’s validators – typically organisations who maintain copies of the ledger, verify transactions and add them to the chain.

These fees are not charged in the digital currency being sent, for example USDC, but instead are incurred in the native token of the blockchain, which in the case of Ethereum is ether (ETH). However, as a single ethereum token is currently worth around $3,500, gas fees on the network are typically charged in a denomination of ETH known as gwei, which is equivalent to 0.000000001 (10⁻⁹) ETH – currently worth slightly less than $0.01. Organisations processing stablecoin transactions directly on-chain therefore have to maintain stocks of ether or other native tokens in addition to the stablecoins themselves – one of several reasons why many companies prefer to use a provider rather than handle the process directly themselves.

While many other Layer-1 blockchains, such as Solana or Stellar, are similar in fee makeup but with variations in the share that is burned, Layer-2 blockchains that sit on top of a Layer-1 such as Ethereum are more complex. For Layer-2 blockchains such as Arbitrum and Base, the gas fee typically comprises an execution fee, a Layer-1 data fee to cover the gas costs for the underlying blockchain and a sequencer fee to cover the costs of the entity handling the transaction. Despite this, these Layer-2 blockchains are typically considerably cheaper than the underlying blockchain as each individual transaction is processed on the Layer-1 chain in a larger bundle known as a rollup – something we’ll unpack in more detail in a future guide.

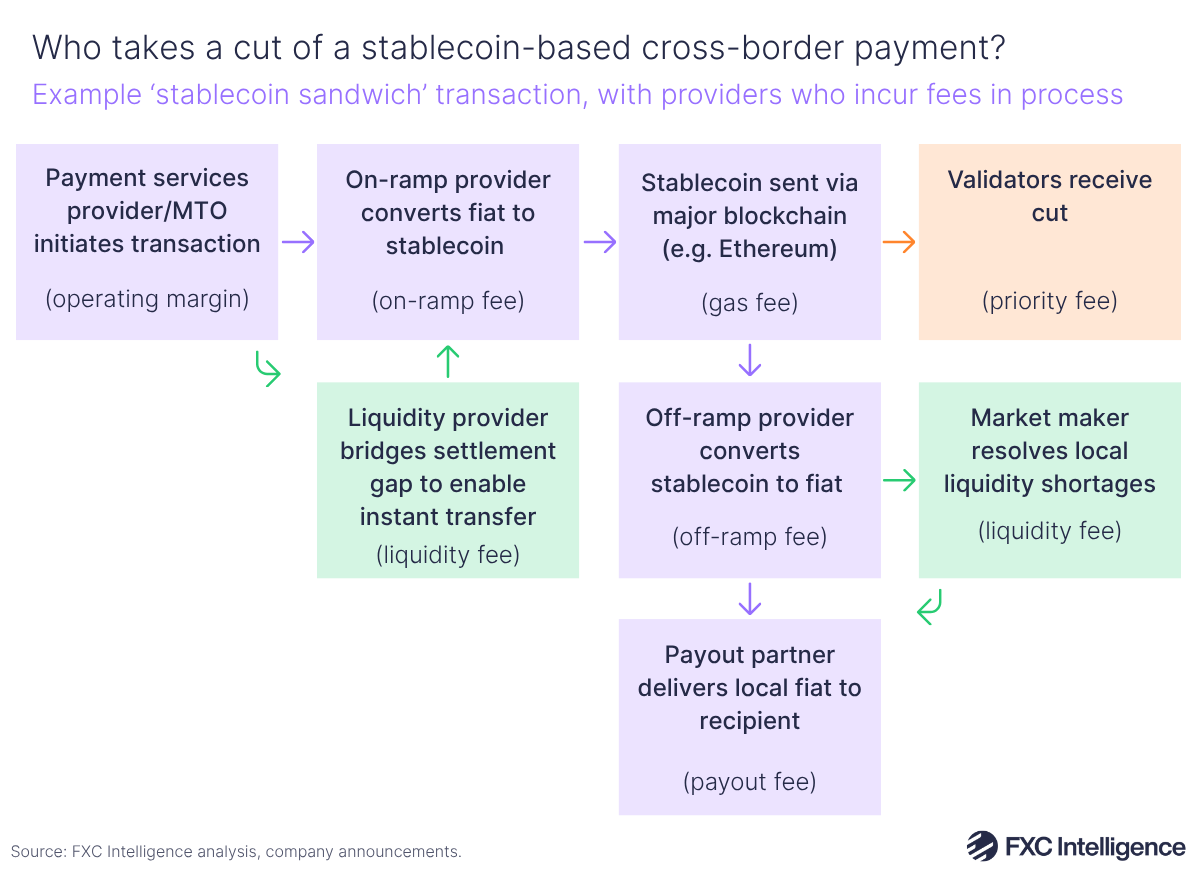

For Layer-1-based payments, gas fees make up the core, but they are only one part of the wider stack that forms a stablecoin transaction. In a ‘stablecoin sandwich’ model, there is also inevitably a margin charged by a payment services provider or money transfer operator, as well as the fee charged by the on-ramp provider, any treasury providers, market makers or liquidity providers involved in the process and the off-ramp provider.

As a result, while in some cases the gas fee alone may be lower than a fiat-based transaction, these additional fees narrow the cases in which it is possible to undercut non-stablecoin cross-border payments – particularly in developed markets.

Nevertheless, there are healthy margins to be gained from stablecoin transactions, particularly in emerging markets, and for companies looking to move money, finding lower cost blockchains can be key. Ethereum is popular not because it is cheap – it is one of the more expensive options and has significant cost volatility – but because it is widely used and therefore offers good liquidity for major stablecoins. However, other smaller blockchains are countering this, often via the use of incentives, which we’ll be unpacking in more detail next week.

In the meantime, if you are exploring using stablecoins for cross-border transactions, learn how FXC Buyer’s Guide: Stablecoin Payments Infrastructure can help you understand the market and identify the providers that fit your needs.