Our Buyer’s Guide: Stablecoin Payment Infrastructure is now out (learn more about purchasing a subscription or read the executive summary), so each week we’re digging into the technical side of the stablecoin payments world to mark its launch. And the latest topic is the subject of launching a stablecoin.

While companies do not need to launch their own stablecoins to make use of the technology in payments, there are those that choose to do so, including Western Union, which last week announced that it was launching the US Dollar Payment Token (USDPT) in H1 2026. Issued via Anchorage Digital Bank on the Solana blockchain, the stablecoin is intended to simultaneously support Western Union’s treasury capabilities as well as facilitate global movement of money.

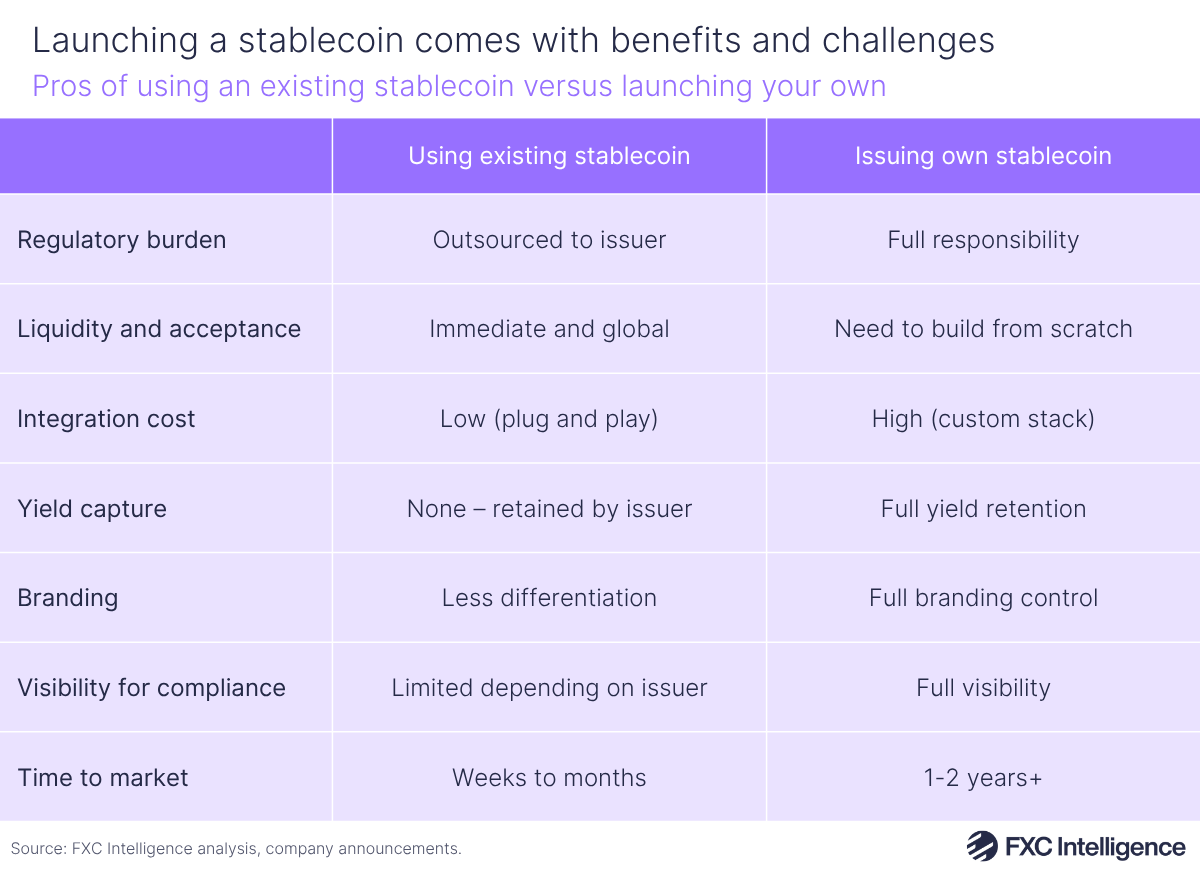

However, Western Union could achieve similar results using a widely available stablecoin such as USDC – this would involve significantly lower costs in the process, but would remove critical branding and revenue opportunities that having its own stablecoin brings. So when is launching a new stablecoin the right option and how is it achieved?

How a new stablecoin is launched

If a company wishes to launch a stablecoin themselves, they will need to decide which jurisdiction the stablecoin will be issued from and under what licence. Once they have determined this, they will need to set up reserves and banking relationships, which includes establishing at least one segregated reserve account at a custodial bank and defining reserve composition. They will also need to establish documentation and management procedures for reserves, as well as appointing an independent body to provide reserve transparency.

Once this is achieved, the company will then need to build the smart contract infrastructure to enable critical elements such as the minting and burning of stablecoins, as well as transfer and blacklist functions and role-based permissions. This may involve adhering to certain token standards, and once complete the process will need to be tested and audited.

After this has been completed, on-chain contracts will need to be linked with off-chain banking infrastructure so that money can be moved in and out of the stablecoin, before finalising reporting processes and building partnerships with exchanges, wallets and payment processors. Growing liquidity is key, so the company may also look to incentivise usage, such as by sharing revenue earned on the stablecoin’s reserves.

This process is complex and challenging, so for many companies it is better to partner with a dedicated stablecoin issuer.

The pros and cons of launching a stablecoin

Launching a stablecoin is not the right fit for every company, however there are a number of reasons why it can be an appealing option, one of which is the control it provides over reserves, governance and yield. Companies can use the interest earned on their stablecoin reserves as an additional source of revenue, rather than this going to another provider, such as Circle.

Issuers can also control critical aspects of how a stablecoin is used, including which blockchains it is available on and under which circumstances it is redeemed, allowing it to be tailored to a company’s precise needs. In the case of blockchains, this also provides the ability to select those best suited to the markets being served and move dynamically between multiple chains.

Beyond this, increased visibility into mint and burn activity can be beneficial for compliance activities, while there are also potential brand benefits. Finally, there is the potential to build a money movement network around a stablecoin. We have seen this with Circle’s Circle Payment Network, the Fireblocks Network for Payments and Paxos’ Global Dollar Network – and Western Union is also planning its own similar network.

However, there are downsides to launching a stablecoin. In addition to significant resource requirements, issuing a stablecoin moves a company into a higher category of financial compliance. Furthermore, the need to hold full reserves for the stablecoin ties up working capital, while any wrong moves or challenges opens up a company to reputational risk that it would not face with a third-party stablecoin.

Perhaps the most crucial challenge, however, is the effort required to build sufficient scale in any new stablecoin. When a stablecoin launches, it has zero liquidity and utility and a company has to generate demand. As liquidity grows, this increases the utility through network effects, but generating initial support is intensely challenging. With any new stablecoin, there is always the risk that it will ultimately not achieve sufficient scale to sustain itself.

We’ll continue our series on stablecoin infrastructure next week. If you are considering adding stablecoins to your technology stack, FXC Buyer’s Guide: Stablecoin Payment Infrastructure is designed to help you make sense of the market and identify the right partners for your needs. Learn more about the guide and how it can help your organisation.